Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

April 2024

Vol. 12, No. 4

How Did Cyrus the Great Die?

By Morteza Arabzadeh Sarbanani

As far as we know, Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, probably died around 530 BCE at the age of seventy. Much like his birth, his death is shrouded in myth; various accounts circulated in antiquity, only a few of which have reached us through Classical authors. Herodotus reports that Cyrus died in a battle against some nomadic Iranian tribes in eastern Iran. Similarly, Ctesias reports that Cyrus died of a wound during his last battle in eastern Iran. By contrast, Xenophon considers the death of Cyrus to be natural. These three Greek authors are our primary sources to investigate the death of Cyrus, as all the later Greek and Roman historians who also wrote about this issue (e.g. Strabo, Justin) were influenced by them. In a 2021 article (in Persian), I attempted to find the most accurate account in light of Persian evidence such as the Behistun inscription and Cyrus’ tomb in Pasargadae.

The Persian Evidence

The value of current Persian evidence regarding Cyrus’ death has been underestimated. I like to highlight two facts very briefly here. The first and most obvious one is that Cyrus’ tomb in Pasargadae (Mašhad-e Morḡāb) in southwest Iran is far away from where the last battle of Cyrus took place. The second one is that according to the Behistun inscription, the eastern Scythians were subjects of the Persian Empire during the incidents right after the death of Cambyses (Cyrus’ successor). Since we do not have any evidence regarding the subjugation of the Scythians by Cambyses, these nomadic Iranian tribes must have been annexed to the Persian Empire by Cyrus the Great.

Tomb of Cyrus at Marv Dasht, ancient Pasargadae. Photo by Soheil Callage, CC-By-SA 4.0.

The famous ancient monument of Pasargadae lacks any inscription to help us determine its exact nature with certainty. That is why some modern historians have questioned whether it is truly the tomb of Cyrus the Great. However, thanks to the Greek evidence, and some inscriptions near the monument, there is no reason to question the authenticity of Cyrus’ tomb. The oldest testimony on the tomb of Cyrus the Great is Strabo’s description of this monument (Geography 15.3.7–8). Strabo never visited Persia, but he used the works of earlier historians such as Aristobulus and Onesicritus, who had visited many cities and regions of Persia during Alexander’s campaigns. Aristobulus’ description of the tomb of Cyrus the Great as reported by Strabo is consistent with the current famous structure ascribed to the tomb of Cyrus in Pasargadae. Arrian (6.29.5–8) also gives a relatively detailed description of the tomb of Cyrus, and the same as Strabo, his source is Aristobulus.

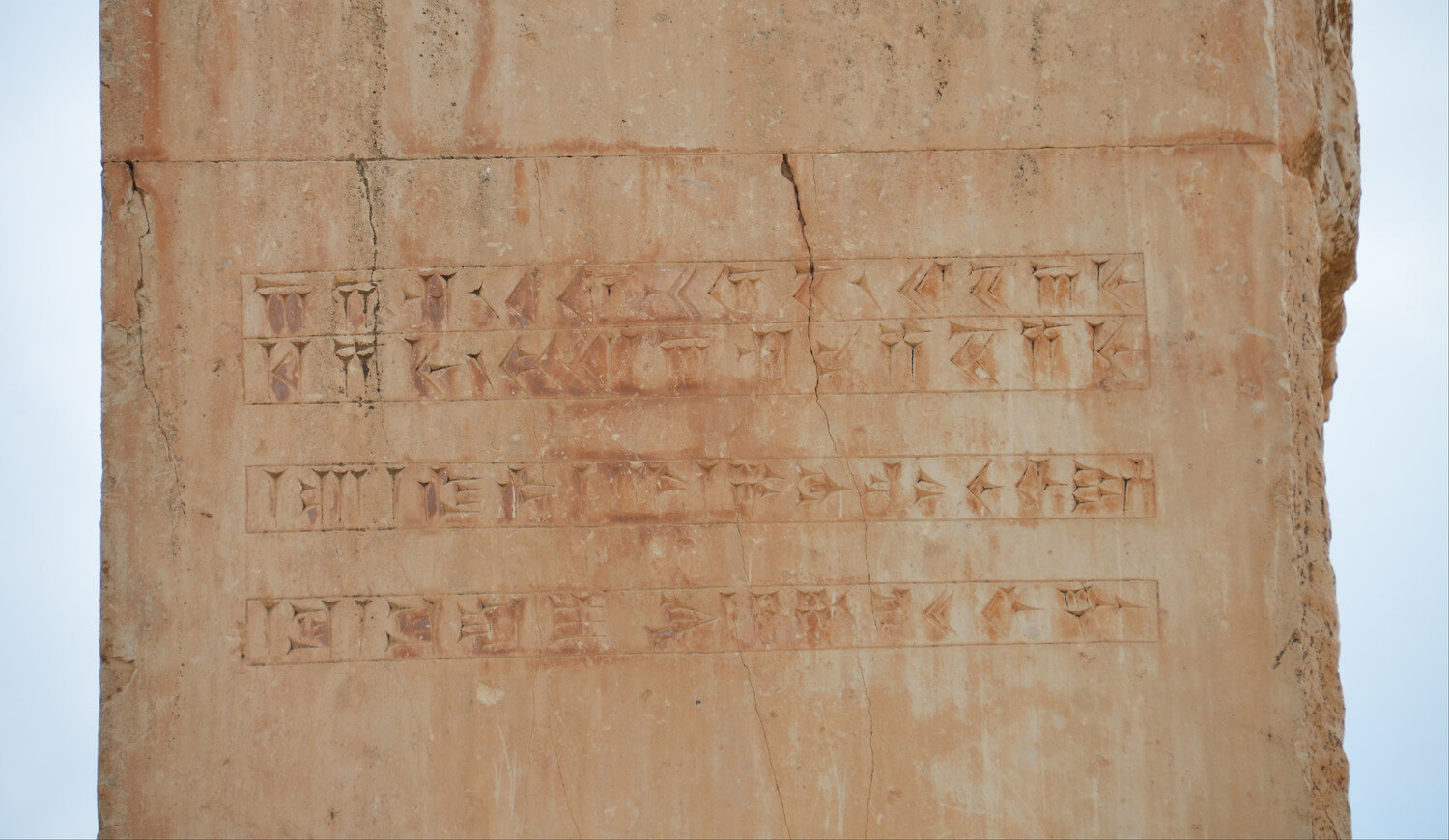

Aside from these historians, the most tangible evidence proving that Cyrus the Great rests in Pasargadae is the inscriptions near the building attributed to his tomb, known as CMa, CMb and CMc. These inscriptions all have Old Persian, Elamite, and Akkadian scripts, and in all of them, the name of Cyrus is mentioned. Although most scholars believe that these inscriptions were composed after the death of Cyrus and during the reign of Darius the Great, their presence at Pasargadae reinforces the association of the site and the tomb with Cyrus.

Persian Inscription from Palace S near Cyrus’ Tomb at Pasargadae: “I, Cyrus, the King, an Achaemenid” (CMa). Photo by Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0.

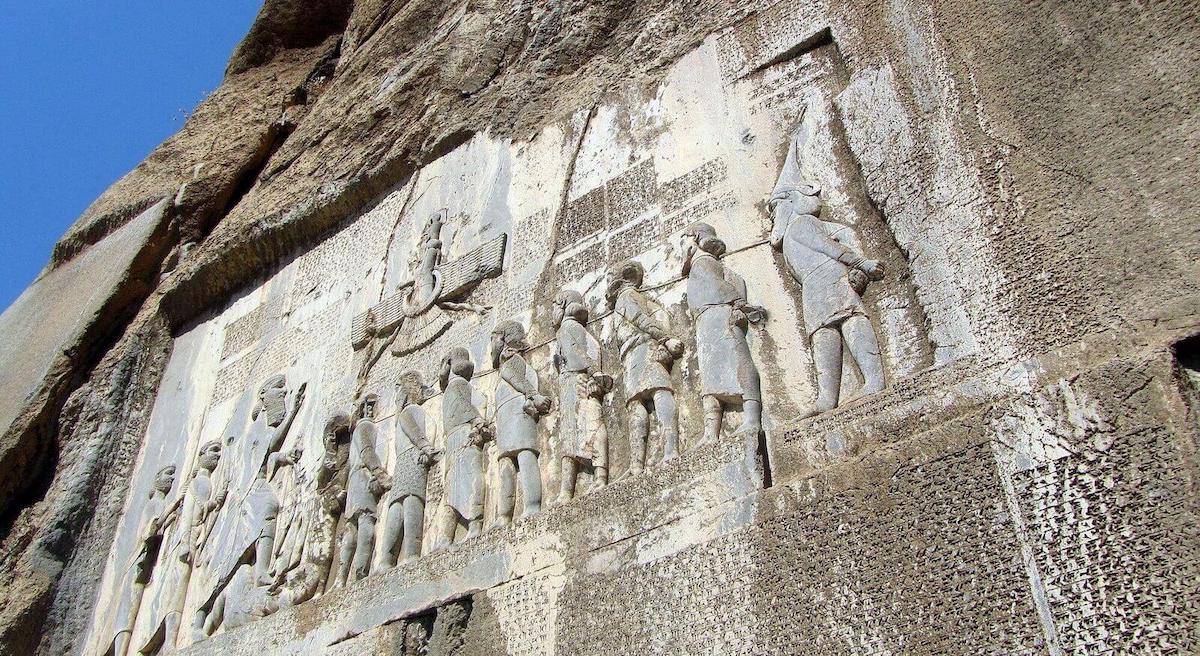

The Behistun inscription, carved into a cliff face at Mount Behistun in the Kermanshah Province and disseminated throughout the empire via copy by Darius I, can also throw light on the discrepancies in the recorded accounts of the death of Cyrus the Great. As the inscription recounts Darius’ accession to the throne and the period at the beginning of his reign, it helps us to study the political status in the eastern regions of the Persian Empire at the time of the death of Cambyses, Cyrus’ son and successor.

Relief and trilingual inscription of Darius I, Behistun, ca. 520 BCE. Photo by Hamidreza Sorouri via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Based on the historical sources, we are reasonably confident that Cyrus the Great marched to the east of Iran at least twice: once after the conquest of Lydia and Asia Minor and again after the conquest of Babylonia. The first campaign resulted in a Persian victory (Herodotus 1.177). It is the outcome of the second eastern campaign that can help us to understand how Cyrus the Great died. According to the Behistun inscription, the Scythians and Bactrians living in the east and northeast of Iran were subjugated before Darius the Great came to the throne:

By the favor of Ahuramazda I am King; Ahuramazda bestowed the kingdom upon me. These are the countries which came unto me: by the favor of Ahuramazda I was king of them: Persia, Elam, Babylonia, Assyria, Arabia, Egypt, (those) who are beside the sea, Sardis, Ionia, Media, Armenia, Cappadocia, Parthia, Drangiana, Aria, Chorasmia, Bactria, Sogdiana, Gandara, Scythia, Sattagydia, Arachosia, Maka. (The Behistun Inscription [DBI], §5-6, translation from R. Kent, Old Persian, p. 119)

This means that either Cambyses or Cyrus conquered those countries. Since there is not a single piece of evidence that suggests Cambyses campaigned in the East, it is reasonable to assume that the real conqueror was Cyrus the Great. Therefore, we can assume that Cyrus the Great must have succeeded also in his second eastern campaign.

The Greek Accounts Revisited

Now let’s reexamine our primary Greek sources based on the Persian evidence. I start with Xenophon (Cyropaedia 8.7), whose account is the strangest one. Xenophon begins his narrative with Cyrus dreaming that he has gone to meet the gods; upon waking, he goes to the holy mountain of the Persians to commune with the gods for the last time. He returns to the palace and after resting on his throne for two days, calls the elders of the country to his side to express his final wishes. Xenophon’s narrative is mostly concerned with Cyrus’ final words and wisdom, especially addressed to his two sons (Cambyses and Bardiya). There is no mention of war with the tribes of eastern Iran, and the Persian king dies in full power, with the utmost pride, and in peace at home in his bed in Pasargadae. Although Xenophon’s account contains many romantic and epic elements, in its essence it does not contradict the Persian evidence.

Herodotus’ narrative (1.204–214) is the most popular and well-known. It relates how Cyrus attacked the Massagetae (a Scythian tribe dwelling in the Caspian steppe) and how Tomyris, their queen, defeats the invincible Persian king. In the end, Cyrus is killed and Tomyris defiles his body by cutting off his head and thrusting it in a skin full of human blood as revenge for the death of her son (2.214).

The legend of Tomyris, Queen of the Massagetae, and her defeat of Cyrus has been depicted and retold multiple times throughout history, such as in this painting by Rubens from 1623 in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston (here cropped) and a Kazakhstani film released in 2019.

Although fascinating in terms of romance and epic, Herodotus’ account raises serious questions and goes against the Persian evidence. It suffers from significant geographical errors, it does not reveal why Cyrus invaded the country of the Massagetae, why Tomyris invited Cyrus to cross the river Araxes into Massagetae territory, why the Massagetae invaded the Persian camp against their former agreement, nor how the Massagetae were able to defeat the Persians and kill Cyrus. Even if we ignore all these problems, we cannot justify how Cyrus’ body ended up in Pasargadae in southwest Iran, nor how — if Cyrus was defeated and Cambyses never took his revenge — it is that Darius the Great enumerates the Scythians as subjects of the Persian Empire in the incidents right after the death of Cambyses.

Ctesias’ narrative (as recorded by Photius, Bibliotheca, 72.8) has general parallels to that of Herodotus’, as Cyrus eventually dies due to a wound that he takes in a war against the Massagetae (specifically the Derbices, a sub-tribe, and their king Amoraeus). However, in his account, the Persians are victorious. This is consistent with the evidence from the Behistun inscription. Moreover, Ctesias relates how Cyrus chose his son Cambyses as his successor on the verge of death, and how after he died, Cambyses took his body to Persia. Therefore, Ctesias’ account is completely in line with the Persian evidence.

In all our primary accounts regarding Cyrus’ death, epic and romance play a significant role. However, only Ctesias’ narrative is completely in line with the Persian evidence. Although Xenophon’s account is consistent with the Persian evidence, it should likely be dismissed, as most historical sources have ascribed the death of Cyrus to his campaign against nomadic Iranian tribes in the farthest parts of his empire.

Morteza Arabzadeh Sarbanani holds a Master’s Degree in ancient Iranian history from the University of Tehran.

Further Reading:

Arabzadeh Sarbanani, M. and A. Rasouli. 2021. Investigation of the death of the founder of the Achaemenid Dynasty. Tārīkh-I Īrān (IRHJ; Journal of Iran History) 13(2): 67-84. (In Persian) Available: https://irhj.sbu.ac.ir/article_100951.html

Dandamayev, M. 1993. “Cyrus II The Great”, Encyclopedia Iranica, Vol. VI, Fasc. 5, 516–521. Available: https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/cyrus-iiI

Kent, R.G. 1953. Old Persian: Grammar, Texts, Lexicon. New Haven: American Oriental Society. Available: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.32106016799493

How to cite this page:

Arabzadeh Sarbanani, M. 2024. How did Cyrus the Great die? The Ancient Near East Today 12.4. Accessed at: www.asor.org/anetoday/2024/04/cyrus-the-great.

Want To Learn More?

Migrations and Invasions: How Steppe Nomads Shaped the Near East

Migrations and Invasions: How Steppe Nomads Shaped the Near East

by Kenneth W. Harl

Nomadic peoples dwelling on the Eurasian steppes played a major role in shaping the civilizations of the Near East. Here are three occasions when they changed the course of history to define the modern Middle East. Read More

A Minor Biblical Prophet Lives Again—Among the Dead

by Amy Erickson

Jonah is but a blip in the Hebrew Bible, with the thinnest of prophetic credentials. So why is his image so popular in early Christian funerary art? Read More