Migrations and Invasions: How Steppe Nomads Shaped the Near East

January 2024 | Vol. 12.1

By Kenneth W. Harl

Nomadic peoples dwelling on the Eurasian steppes have historically played a major role in shaping the civilizations of the Near East. On three occasions, nomads quitting their ancestral grasslands for the Near East have changed the course of civilization. Their gateway has been Transoxiana (Arabic Mawarannahr), the lands between the Oxus (Amu Darya) and south of the Jaxartes (Syr Darya) Rivers that today comprise Uzbekistan, western Tajikistan, southern Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Kyrgyzstan. This region sustained irrigated agriculture and cities from early Antiquity, but also its grasslands offered pastures for the herds and flocks of nomads. On three occasions, nomadic peoples of the Eurasian steppes crossed the Jaxartes River and entered the Near East. In so doing, they defined the modern Middle East.

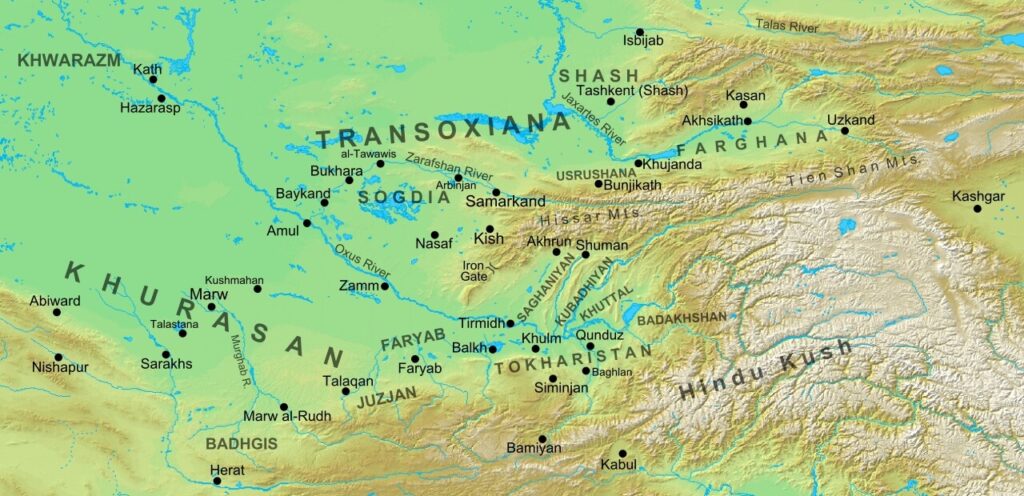

Map of Transoxiana, between the Oxus and Jaxartes (Syr Darya) Rivers, overlapping modern Uzbekistan, western Tajikistan, southern Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Kyrgyzstan. Map by Cplakidas / Wikmedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Syr Darya (Jaxartes River), as seen in Khujand, Tajikistan. Photo: Shavkat Kholmatov via Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

The first of these nomadic migrations occurred in the late third millennium BCE, when Indo-Aryan speaking nomads, likely members of the Sintashta Culture, migrated from their homeland between the Ural and Volga Rivers into Transoxiana, then home to the agriculturalists of the Bactria-Margiane Archaeological Complex (also sometimes referred to as the Oxus Culture). These pastoralists brought the modern horse and light chariot that revolutionized warfare across Eurasia in the Late Bronze Age.

The Indo-Aryans, from ca. 1500 BCE, crossed the Hindu Kush into the Indus valley, known in cuneiform texts as Meluuha, and defined the cultural and religious foundations of Hindu India. Centuries later, their Iranian-speaking kinsman, Medes and Persians, followed the route of the later Silk Road across Iran to settle, respectively, in northwestern Iran around Ecbatana (today Hamadan), and in southwestern Iran, Persia (today Fars). Cyrus the Great (559–530 BCE) conquered a vast Persian Empire from the Aegean to the Hindu Kush. The Great Kings of Persia depended on Iranian horse archers, the invincible light cavalry of steppe nomads since the early Iron Age (ca. 1000–700 BCE). Cyrus’ heirs extended the empire from the Nile to the Indus, founding the greatest ancient empire prior to Rome. Iran has ever since been a premier political and cultural power in the Near East. The Iranians, conscious of their imperial heritage, still view themselves as the masters of the Near East.

Later Iranian monarchs of the Arsacid (247 BCE–224 CE) and Sassanid (224–651 CE) dynasties strove to control the lands of Transoxiana, and to guard against the nomadic peoples north of the Jaxartes River. Repeatedly, nomadic peoples — Tocharians, Hephthalites, and Gök Turks — crossed the Jaxartes and wrested Transoxiana from Iranian control. Even so, these lands remained homes to fabled caravan cities, notably Bukhara and Samarkand, and the populations, while embracing many faiths, speaking the eastern Iranian tongue Sogdian — the language of commerce along the Silk Road as late as the eleventh century.

With the Muslim conquest of Iran, the Arab governors of Khorosan (the eastern Iranian plateau), mastered Transoxiana between 673 and 754 and so they succeeded to the task of defending the Jaxartes frontier against nomadic Turkish tribes which had rapidly spread across the Eurasian steppes since the sixth century. As the Caliphate fragmented after the death of al-Amin (809–813), emirs of Iranian or Turkish origin carved out regional states as deputies of the Sunni Abbasid Caliph of Baghdad. They depended on armies of slave soldiers (mamluks) obtained in trade with Turkish tribes on the Eurasian steppes.

Map of the Seljuk Empire in 1090 CE. Credit: Ktrinko via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0.

From these warring Turkish tribes, the Seljuk Turks burst into the Near East in the second significant migration of steppe nomads during the eleventh century. The Seljuk Turks transformed the Islamic world. The Seljuk Sultan Tughrul Bey defeated his Ghaznavid overlord Masud, who was himself an Iranian dynast of Turkish origin, at the Battle of Dandanaqan in 1040. Tughrul Bey then overran Iran and went on to restore the authority of Abbasid Caliph in 1055.

In 1071, Sultan Alp Arslan, the nephew of Tughrul Bey, decisively defeated the Byzantine army at Manzikert and so opened Anatolia to settlement by Turkish tribes who forged there a new Muslim, Turkish heartland over the next three centuries. The newcomers also settled on the grasslands of Transoxiana and, Azerbaijan, and so brought their language and way of life into the Near East. Foremost, the Turks revived the military power of Islam, and they have ever since provided the best soldiers of Islamic regimes. The Seljuk Turks, who long adhered to their nomadic mores, proved hard masters to the urban dwellers and agriculturalists of the Near East, but they had embraced Islam en masse from the early tenth century. Hence, these nomadic newcomers were given a pass, and accepted as the defenders of Sunni Islam rather than rapacious barbarians invaders.

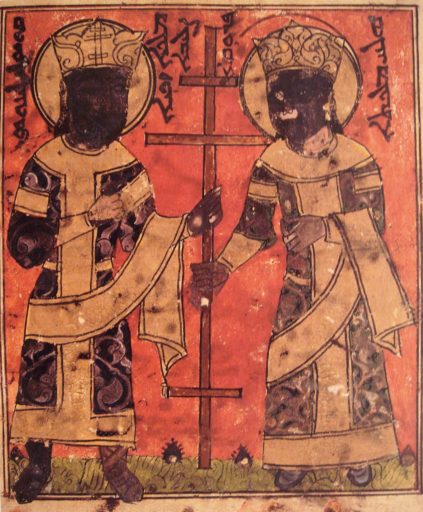

Illustration from a Syriac Bible of Hulagu, Mogol ruler of west Asia, and Doquz Khatun, his wife and Keraite princess, who was also Christian (Church of the East). 13th century. Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain).

Alamut Castle (Iran, Qazvin Province), which served as headquarters of the Nizarites (Assassins) from the 11th to the 13th century until the area was taken over by Hulagu Khan. Photo by Alireza Javaheri via Wikiimedia Commons. CC By 3.0 DEED.

Finally, the Mongols were the nomads who had the most dramatic impact on the Near East. Many scholars still consider the campaigns of Genghis Khan in 1219–1222 and his grandson Hulagu in 1255–1260 as catastrophic for the civilization of eastern Islam. The large-scale massacres of populations and destruction of cities were without precedent. Hulagu destroyed the strongholds in northern Iran of the Nizarites, known popularly as Assassins, but he also sacked Baghdad and executed the Abbasid Caliph al-Musta’sim Billah in 1258. These Mongol invasions had two long-term consequences.

An example of how Ilkhanid period artists adopted imagery from Chinese iconography: tile with the image of a Phoenix. From Iran, probably Takht-I Sulaymän, late 13th century; height 37.5 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art 12.49.4. (Public Domain).

First, thousands of Iranians and Turks fled west from Transoxiana. Foremost was the Persian poet and mystic Jalal al-din Rumi (1207–1273), the Mevlana, who relocated to Konya and founded the order of the Deverishes who were so vital in converting the Byzantine populations of Asia Minor to Islam. The Mongols also tipped the linguistic balance from eastern Iranian to Turkish languages in Transoxiana. Second, the destruction of Baghdad by Hulagu in 1258 shifted the political and cultural axis of Sunni Islam to Cairo, and, after 1453, to Constantinople (Istanbul), still the two great centers of the Islamic world to this day. Meanwhile, Hulagu and his heirs ruled as the Ilkhans over the western ulus of the four nations of the Mongol Empire comprising Iraq, Iran and Transoxiana The Ilkhans eventually embraced Islam and the high Persian culture of eastern Islam, but the Ilkhanate fragmented in the mid-fourteenth century. Although Tamerlane (1370–1405) briefly aspired to reunite the Mongol Empire, his empire also fragmented upon his death.

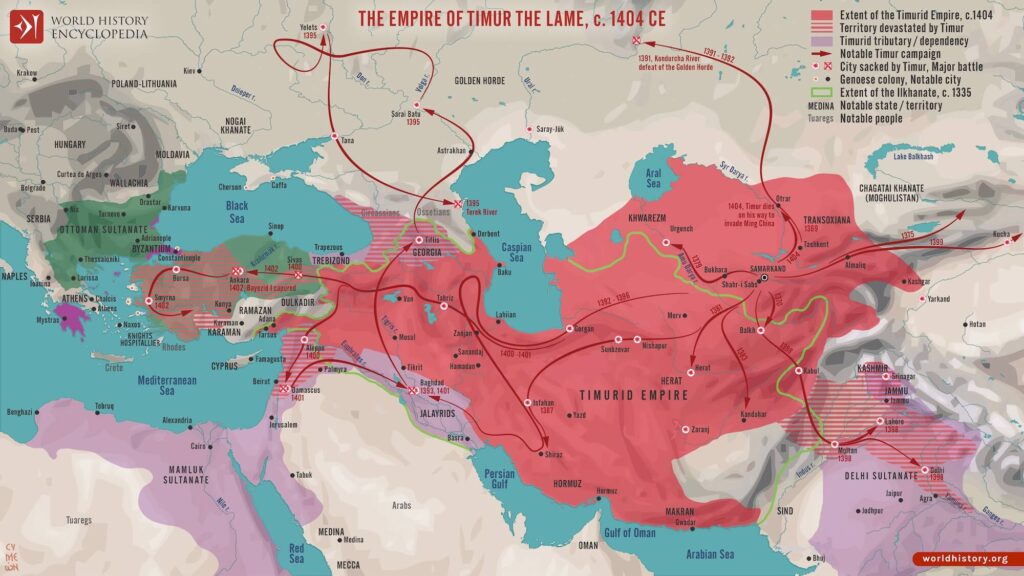

Map of campaigns and empire of Timur (Tamarlane), a Turko-Mongol warlord from Transoxiana. The empire included all of central Asia, greater Iran, Iraq, parts of southern Russia and the Indian subcontinent. Timur’s forces defeated the Mamluks in Syria and the Ottomans at Ankara. Map by Simeon Netchev. CC By-SA.

The future of Iran rested with a new Turkish nomadic confederation, the Kızılbaşlar (“Red Turbans”), the warriors of the Safavid Shahs who turned Iran into an imperial Shi’ite in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The Safavid Shahs proved the most dangerous foe to the Ottoman sultans, who united most of Sunni Islam, for mastery of the Near East and the historic Muslim capitals. The geopolitical and religious alignments ultimately wrought by the Mongol invasions, especially the Turkish-Iranian rivalry, have endured down to this day.

Kenneth W. Harl is Professor Emeritus in the Department of History at Tulane University. His book, Empire of the Steppes: The Nomadic Tribes Who Shaped Civilisation, has recently been published by Bloomsbury Press.

How to cite this article

Harl, K. W. 2024. “Migration and Invasion: How Steppe Nomads Shaped the Near East.” The Ancient Near East Today 12.1. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/harl-nomads-eurasian-steppes/.

Post a comment