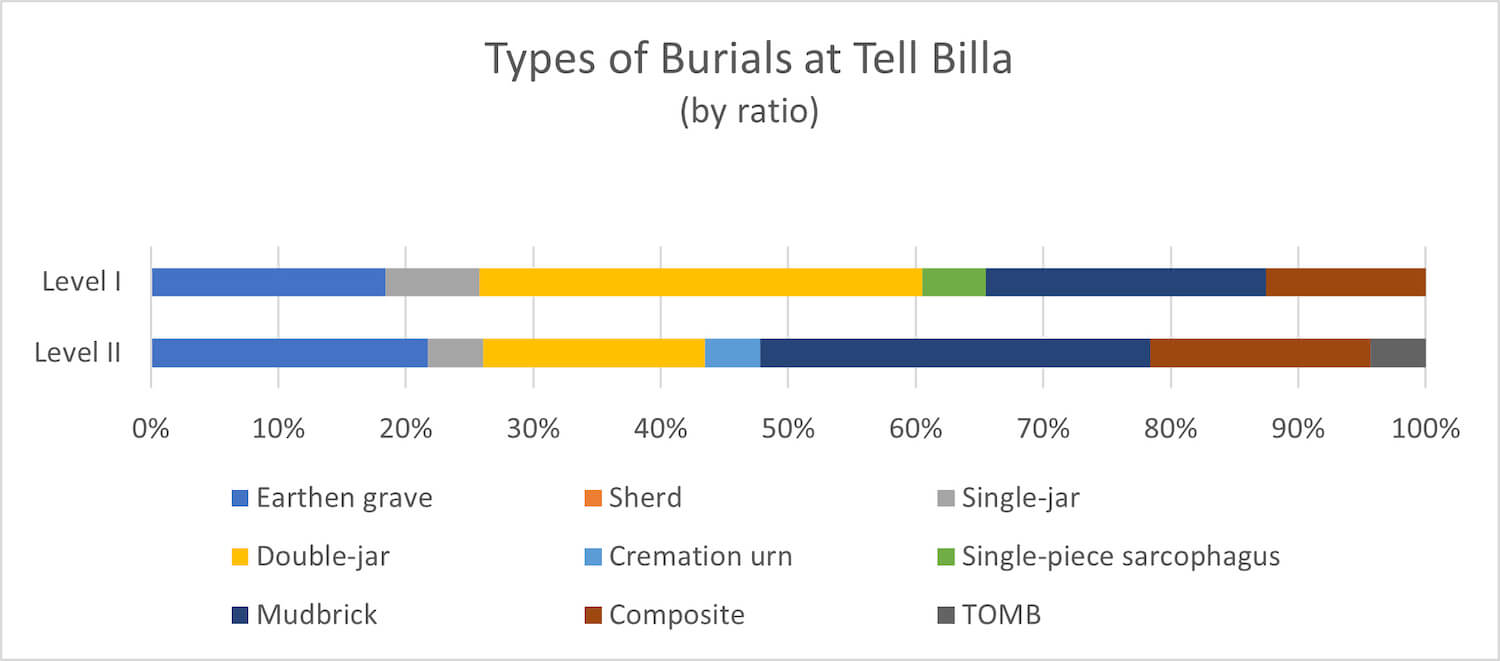

When assessed with a long-term perspective, overarching trends in mortuary culture serve as a kind of “litmus test” indicator of social change. Here we have been able to see how shifting burial practices in the Assyrian capital and in a provincial center indicate differences in non-elite perception and adoption of Assyrian cultural practices. At an individual level, this suggests an exposure to imperial mortuary practices and a normalization of adopting Assyrian practices. More broadly, it suggests that non-elite Assyrian subjects came to accept and replicate aspects of imperial society which, to our knowledge, were not forced through imperial channels. Because funerary culture is one of the most conservative forms of practice, the implications of its change under Assyrian imperialism at a non-elite, provincial level point to the depth of cultural influence that Assyria had over its subjects which has been difficult to identify by other means.

I put forward the conclusion that the residents of Šibaniba began to see themselves as fundamentally/culturally “Assyrian” as the hegemony of the Assyrian Empire grew. No evidence exists for a purposeful imposition of mortuary traditions by Assyrian rulers. Rather, the mortuary practices of the Assyrians seemed very much like a “take it or leave it” aspect of their lives. When many of those living in the Empire decided to “take it,” it was an unimposed choice — reflecting not the demands of a dominant imperial power, but rather the purposeful adoption of new traditions into personal and community-driven narratives.

Petra M. Creamer is Assistant Professor of Ancient Near Eastern Studies at Emory University. She directs the Rural Landscapes of Iron Age Imperial Mesopotamia project in Iraqi Kurdistan.

Further Reading and Sources:

Hauser, S. 2012. Status, Tod und Ritual: Stadt- und Sozialstruktur Assurs in neuassyrischer Zeit. Harrassowitz.

Miglus, P. 1996. Das Wohngebiet von Aššur. Stratigraphie und Architektur. Gebr. Mann Verlag.

Miglus, P.A. 1999. Stadtische Wohnarchitektur in Babylonien und Assyrien. (BaF 22) Mainz: Ph. Von Zabern.

Miglus, P., K. Rader, & F.M. Stępniowski. 2016. Ausgrabungen in Assur: Wohnquartiere in der Weststadt. Harrassowitz.

Pedde, F. 2015. Gräber und Grüfte in Aššur II: Die mittelassyrische Zeit. Harrassowitz.