Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

August 2023

Vol. 11, No. 8

The Egyptian Conceptualization of the Otherworld

By Silvia Zago

The belief in life after death is one of the most defining aspects of Egyptian culture, which has fascinated the outside world for millennia. The sources affording us a glimpse into notions of the otherworld are many and range in date from the early Pharaonic (~3000 BCE) to the Graeco-Roman period (332 BCE – 395 CE). Although there was no single conceptualization of death and the next life, one core notion always formed the basis of all afterlife beliefs: death was merely a temporary condition, a transition towards a new status known as akh (lit. “effective being”), which the deceased hoped to gain after overcoming a series of obstacles lying on their path to rebirth. For the ancient Egyptians, achieving immortality was of paramount importance: the alternative was a second, ultimate death, which would wipe out one’s existence in the beyond as well as any memory of them in the society of the living.

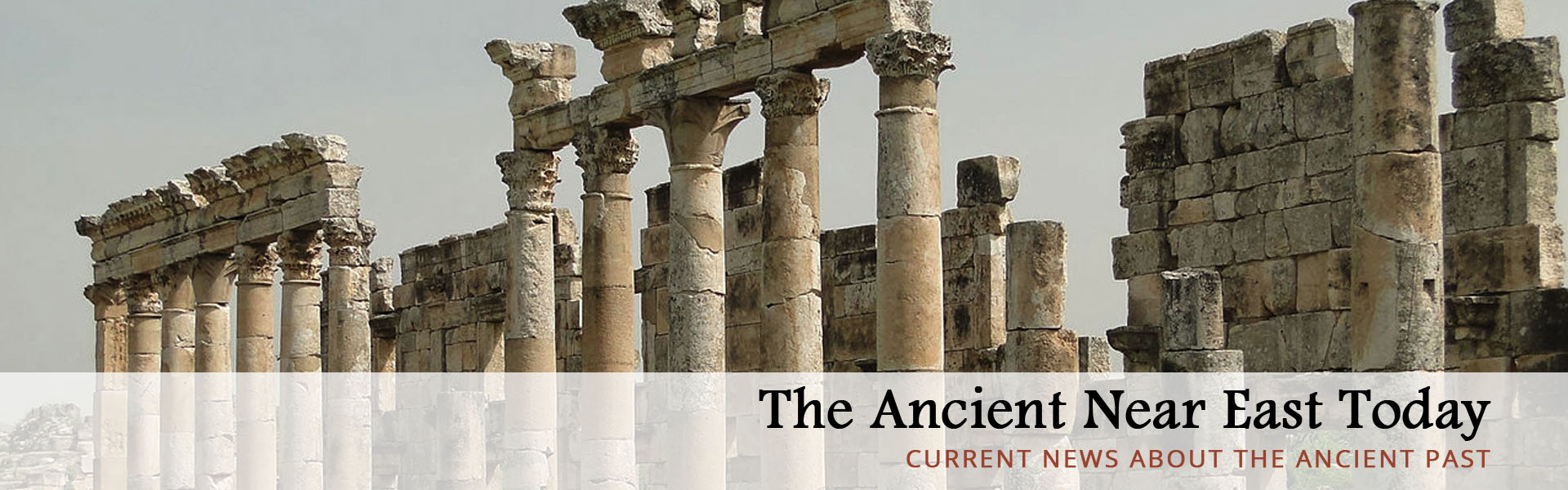

Figure 1. Interior of the antechamber of the pyramid of Wenis, Saqqara, 5th Dynasty. Photo by Victoria Almansa Villatoro.

Among the most important sources to reconstruct Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife are the funerary texts. Originally an exclusive prerogative of royalty, their use later extended to the elite of the population. Funerary texts were inscribed onto tomb walls or on items of the burial assemblage that were deposited in tombs with the deceased, such as coffins and papyri. Their goal was to ensure that the deceased would travel safely towards and through the next world and that they would be rejuvenated and reborn for all eternity. Ever since the earliest funerary texts (Pyramid Texts) appeared inside the pyramids of kings and queens of the late Old Kingdom (2375–2160 BCE), the deceased were associated with the cycle of the celestial bodies (Figure 1). Among the stars, the sun provided the perfect template of daily “death” (sunset) and “rebirth” (dawn), which everyone aspired to emulate. This is the reason why the West was identified with the place where the deceased continued living after death — albeit in another spatial and temporal dimension — called Duat. Despite identifying the Duat as the otherworld and thus a core notion of the afterlife beliefs, pinning down its features and location is no easy feat. It is described variously across sources and often endowed with contradictory features within the same text, depending on the contexts and functions it has. Moreover, new concepts were introduced over time, adding layer upon layer of complexity to this multifaceted notion.

Ever since the Pyramid Texts, different traditions of the otherworld existed side by side. One was modeled after the sun god Re and his cyclical path in the sky: upon death, the deceased would ascend to the sky, where they would live forever in the company of the gods and celestial bodies. In this (royal) version of the afterlife, the Duat was therefore located in a celestial domain.

Another (non-royal) tradition entailed resurrection through burial and a new life lived in close proximity to the tomb, within which texts and illustrations re-enacted the earthly world of the deceased. The tomb was conceived as a dwelling for eternity and an interface between worlds, where the living and the dead could (metaphysically) come together on certain occasions and temporarily be reunited (Figure 2).

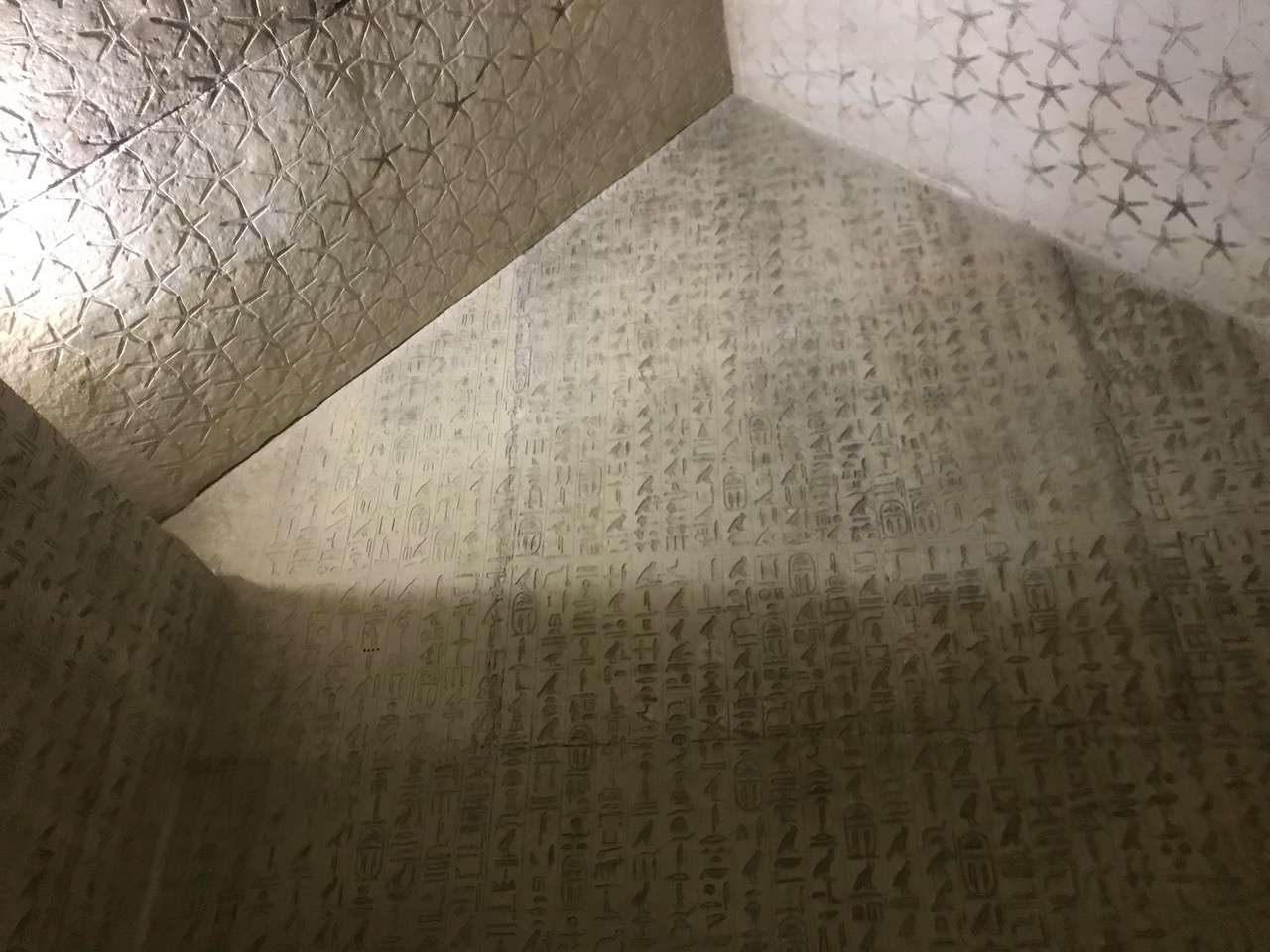

One more tradition of the beyond revolved around the chthonic god Osiris, the prototype of a (divine and royal) individual who died and was brought back to life (in the Duat), and with whom every deceased wished to be identified. This version of otherworld is located in the bowels of the earth (Figure 3).

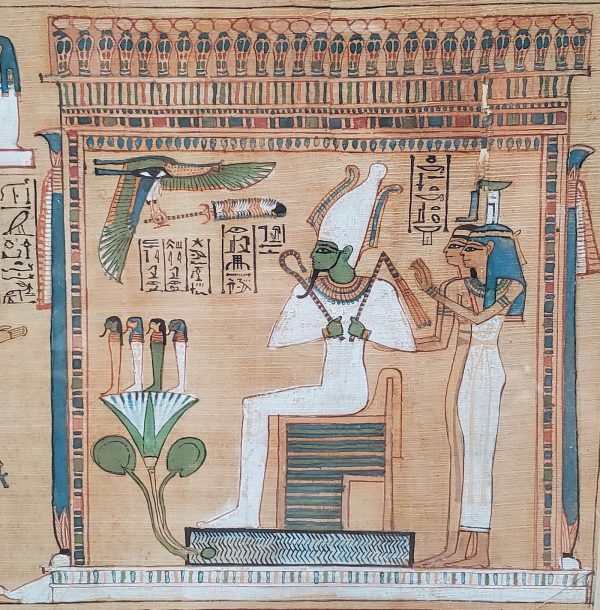

In funerary texts, the Duat exists simultaneously on different cosmic planes encompassed by the diurnal and nocturnal paths of the sun (east to west and backwards) and of the stars (to the north and south of the celestial sphere). Starting with the non-royal Coffin Texts, dating mostly to the Middle Kingdom (~2055–1650 BCE), the Duat evolves into a better-defined locale within the cosmos, distinct from both earth and sky, and yet at times overlapping with (portions of) both (Figure 4).

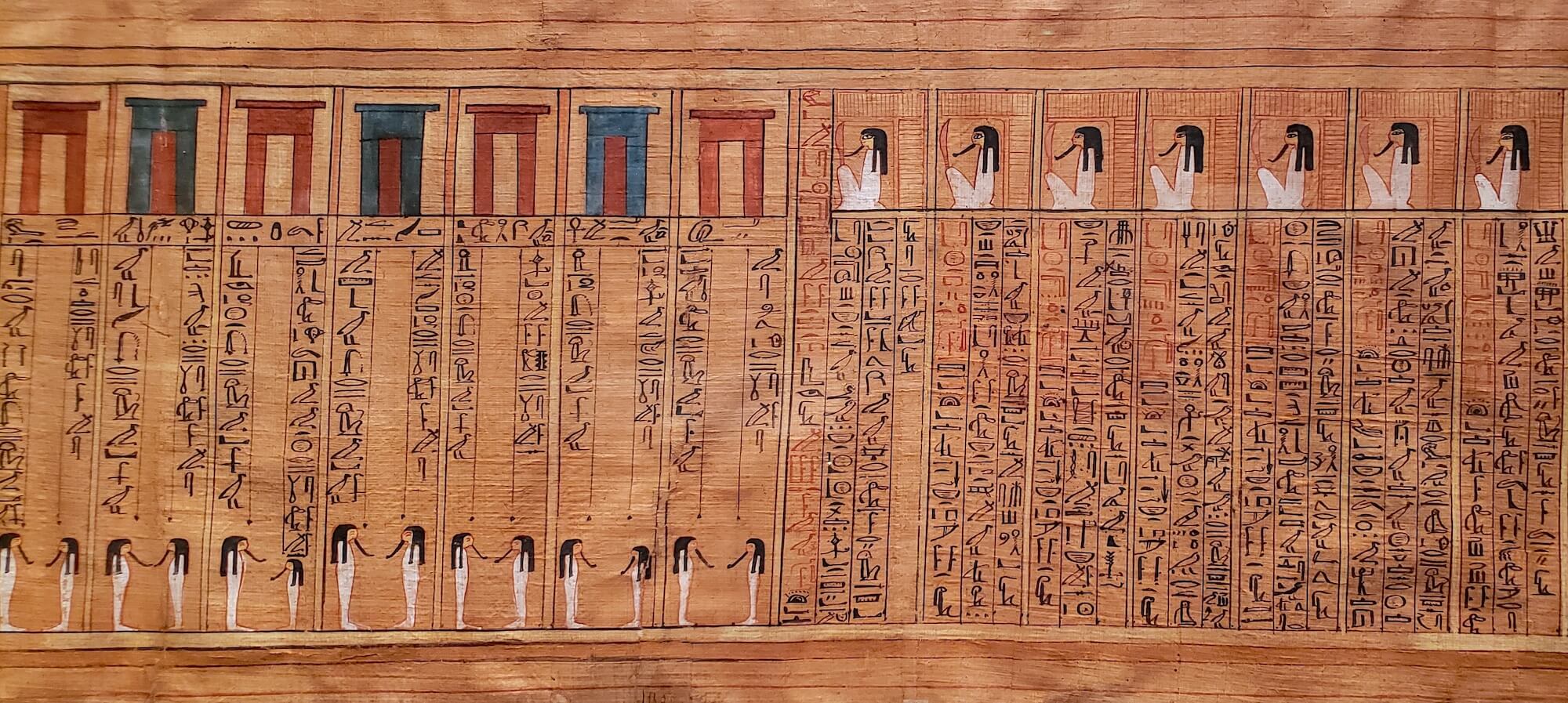

The deceased needed to possess information on the otherworld, such as the names of its denizens, guardians, and various features (e.g., doors), if they wished to live there successfully. Collections of spells such as the Coffin Texts and the Book of the Dead provided said knowledge, also in the form of illustrations (Figure 5).

In the New Kingdom (1550-1069 BC), cosmographic texts illustrating the journey of the sun through the Duat and the visible sky were inscribed in the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings: these are the Netherworld Books and the Books of the Sky. The former focus on the temporary nocturnal union of the solar god Re with Osiris in the Duat, whereby both gods are rejuvenated, and the sun can continue his journey towards rebirth on the eastern horizon in the morning (Figure 6).

In these compositions, the Duat is located primarily in the depths of the earth, where a place of punishment of the solar-Osirian enemies may also appear. It is no coincidence that the royal burials, where these texts appear, are dug deep into the cliffs of the Theban west bank: architecture, texts, and illustrations aimed to transform the tomb into a monumental materialization of the Duat.

The ancient celestial tradition of the Duat resurfaces, on the other hand, in the Books of the Sky, inscribed on the ceilings of Ramesside tombs and in the Osireion of Abydos. These compositions are centered on the celestial goddess Nut, the embodiment of the sky, who was believed to swallow the sun at nightfall (thus becoming “pregnant” with him) and to give birth to him again each morning (Figure 7).

Figure 8. Underside of the lid of the 25th Dynasty coffin of Tariri (Museo Egizio, Turin 2220/02) showing Nut stretched over the deceased in the act of lifting up the solar disk. © Museo Egizio.

Nut was therefore the mother of the sun and of the celestial bodies as well as of the deceased. She personified the notion of death as a return to the origins, namely, to the womb. Inside her, the nocturnal gestation and regeneration of the deceased could take place prior to rebirth in the morning. In virtue of these mythological associations, Nut could be identified with the coffin or the sarcophagus, inside the lid of which she started to be represented from the early New Kingdom, in the act of physically stretching over the deceased, beckoning him to her and protecting him.

At the same time, a text belonging to the religious-astronomical treatise known as the Book of Nut (text L) describes the Duat as whatever is not earth nor sky and is thus situated beyond the boundaries of the created world, outside the celestial vault.

The traditions of the otherworld outlined above coexisted at all times and are constantly intertwined in the sources, and it is therefore impossible to try and separate them. Depending on different (con)texts, the celestial version of the Duat might be emphasized, or rather the subterranean one, or both. The celestial goddess Nut represents the linchpin of all these traditions: as the (mythological) mother of the deceased as well as of Re and Osiris, she encompasses and harmonizes the different destinies that were imagined to be available to the deceased. The Duat could thus be located simultaneously in a celestial domain and in a liminal locale at the threshold between sky and earth, or beneath the latter. What mattered was its functional nature: the Duat was the metaphysical space for the regeneration of the gods, the deceased, and the celestial bodies. As such, it could be identified with the maternal womb of the sky goddess Nut, who served as a paradigm of cyclical gestation and rebirth existing on various cosmic planes, ranging from the sky to what lies beyond it and down to the underworld. Insofar as the immortality of the deceased was guaranteed, the various versions of the Duat did not represent contradictory scenarios but rather complementary ones, aimed to ensure the everlasting survival of the deceased in whichever form they chose.

Silvia Zago is Lecturer in Egyptology in the Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology at the University of Liverpool and Visiting Professor of Egyptology at the University of Pisa. Her book, A Journey through the Beyond: The Development of the Concept of Duat and Related Cosmological Notions in Egyptian Funerary Literature, was recently published by Lockwood Press.

Further Reading

J. Assmann. 2005. Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt. Ithaca (NY): Cornell University Press.

E. Hornung. 1999. The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife. Ithaca (NY): Cornell University Press.

J. H. Taylor. 2001. Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

S. Zago. 2021. ‘A Cosmography of the Unknown: The qbḥw (nṯrw) Region of the Outer Sky in the Book of Nut’, Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 121, 511–529.

S. Zago. 2022. A Journey through the Beyond: The Development of the Concept of Duat and Related Cosmological Notions in Egyptian Funerary Literature. Columbus (GA): Lockwood Press.

Want To Learn More?

Ancient Egyptian Texts for the Afterlife?

By Rune Nyord

Ancient Egyptian funerary texts have been a source of fascination since their discovery. But do these varied texts describe a coherent vision of an afterlife, or is that a 19th century academic projection? Read More

Achieving Divinity: “Golden Mummies of Egypt” at Manchester Museum

By Campbell Price

The primary purpose of the ancient Egyptian mummification ritual wasn’t to preserve the mortal body for the afterlife — it was to transform the deceased into a divine being. Read More

Servant Figurines from Egyptian Tombs: Whom Did They Depict, and How Did They Work?

By Rune Nyord

Scholars have interpreted servant figurines in Egyptian tombs as anonymous toys designed to come to life. A closer look suggests they may have represented a deeper relationship between servants and masters. Read More