INCIDENT REPORT FEATURE: BERENICE

U. S. DEPT. COOPERATION AGREEMENT NUMBER: S-IZ-100-17-CA021

Modern burials and damage continue to occur at the archaeological site of Berenice.

* This report is based on research conducted by the “Safeguarding the Heritage of the Near East Initiative,” funded by the US Department of State. Monthly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change.

The archaeological site of Berenice is located in the Sidi Ekhreibish neighborhood of north-central Benghazi, and is surrounded on three sides by modern buildings. Greek settlement in the area began at nearby Eusperides (also located within the limits of Benghazi) in the early 6th century BCE [1]. Eusperides was abandoned two centuries later due the silting up of nearby lagoons and a new settlement was founded nearby. Around 249 BCE, the town was renamed Berenice in honor of Berenice II, queen of Cyrene and later of Ptolemaic Egypt [2].

In 96 BCE, the entirety of Cyrenaica was bequeathed to Rome upon the death of Cyrenean king Ptolemy Apion, and formed a single administrative unit with Crete. Berenice prospered throughout the Roman era and the beginning of Byzantine rule, but fell into decline in the 6th century CE [3]. By the time of the Arab conquest of Cyrenaica in 643, Berenice was no more than an small village [4].

Berenice marks the westernmost limit of Greek colonization in Africa. Excavations have revealed the remains of a number of Hellenistic and Roman-era structures at the site, including a Hellenistic shrine, several villas and defensive walls, as well as Roman peristyle houses, several civic buildings (possibly including baths), fortifications, and a Byzantine-era church and basilica [5]. Also located on the site is an Italian colonial-era lighthouse built in 1935 [6].

An analysis of DigitalGlobe satellite imagery indicates that there have been several instances of damage to the site of Berenice. Initial damage occurred to a modern building on the southwest part of the site between August 1, 2013 and January 16, 2016. This damage appears to be from heavy shelling.

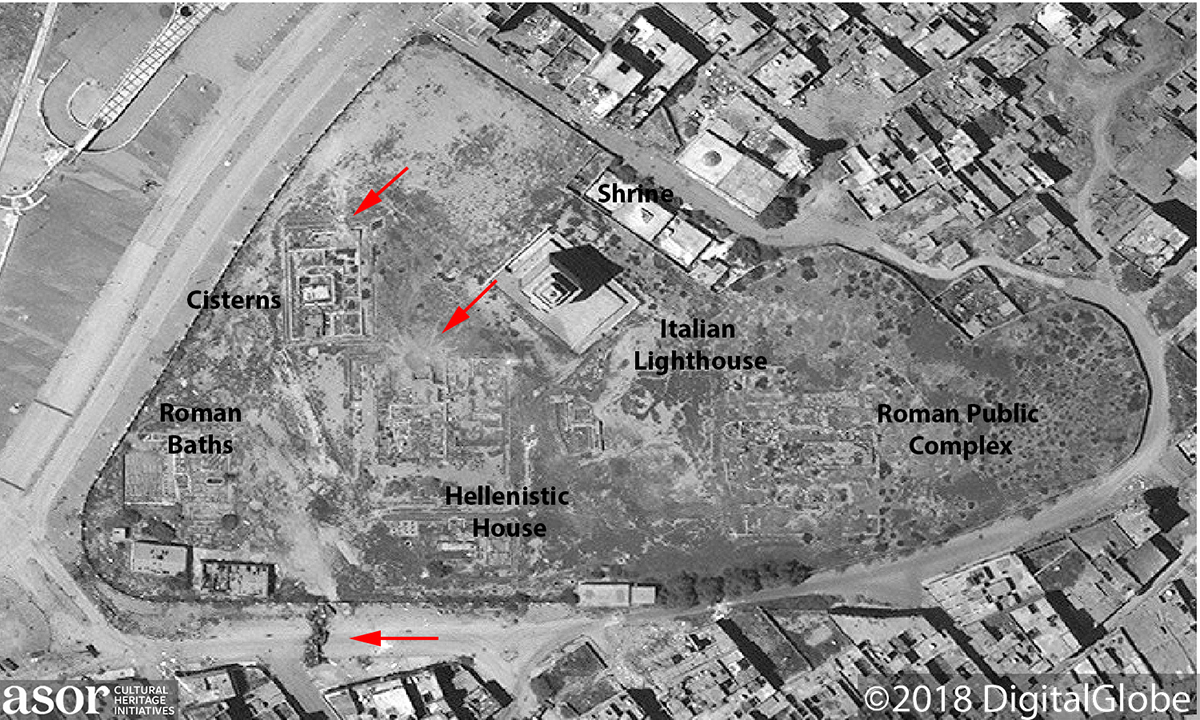

Berenice prior to significant military damage. Some damage to a modern building at the site is indicated with a red arrow (DigitalGlobe NextView License; April 23, 2017)

Damage to the Roman cisterns and the Hellenistic House from possible airstrikes, indicated by red arrows. Additionally, a road block can be seen south of the site (DigitalGlobe NextView License; June 27, 2017)

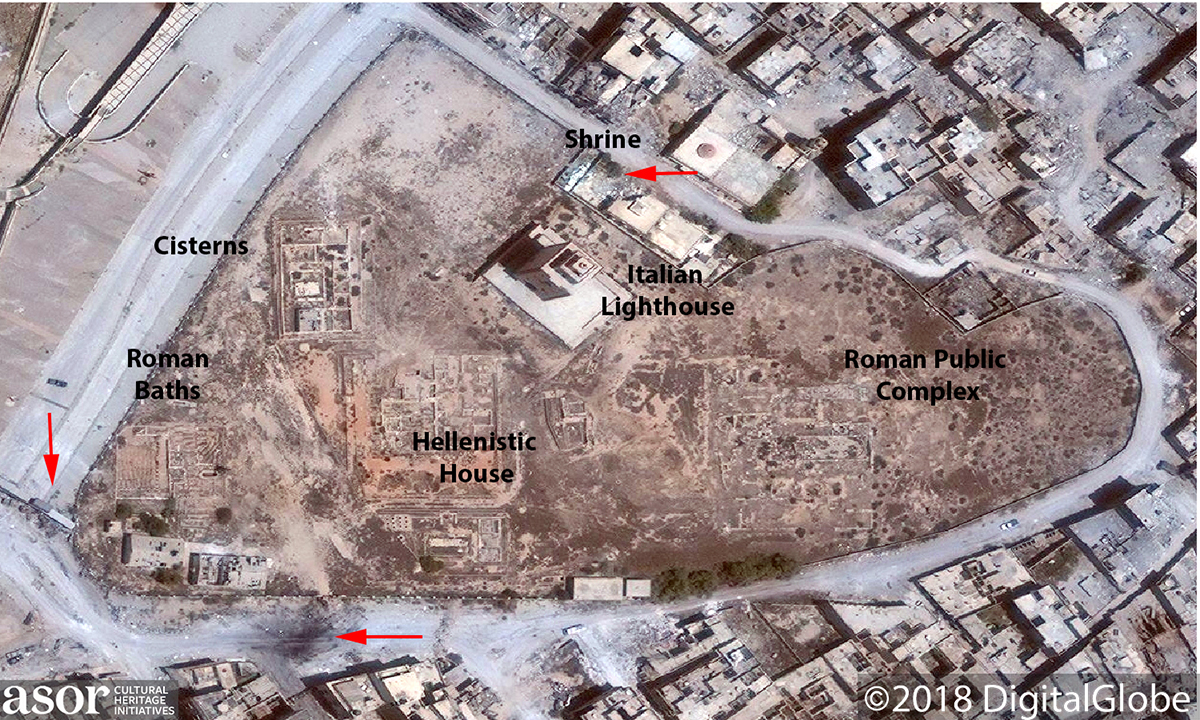

Damage to the Shrine of Sidi Ekhreibish, indicated by a red arrow, along with the destruction of the southern barrier and the construction of the western barrier (DigitalGlobe NextView License; July 24, 2017)

Modern burials within a Roman-era peristyle building, facing south. Tools perhaps used to dig the graves are seen in the foreground and an unburied body is seen in center left (Al Wasat; September 23, 2017)

Another view of the mass gravesite, facing southwest (Al Wasat; September 23, 2017)

More graves just east of the peristyle building (Al Wasat; September 23, 2017)