Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

May 2023

Vol. 11, No. 5

“Proto-Rams”: Piecing Together the Early History of Naval Ram Development

By Stephen DeCasien

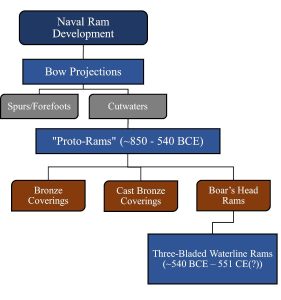

The naval ram was the predominant weapon of navies throughout much of antiquity, playing a decisive role in many consequential confrontations such as the Battle of Salamis (480 BCE) and the Battle of Actium (31 BCE). It continued to play a crucial role in Mediterranean seafaring until shipbuilding techniques changed with the decline of trade and naval warfare around the middle of the 6th century CE, primarily due to the fall of the Western Roman Empire. But where did the naval ram come from? Its origins and early history remain a heated topic of debate among scholars. Given the limited corpus of archaeological, iconographical, and textual evidence, opinions vary on what can be considered a ram or ram-bearing vessel. Even so, we can reasonably divide ram development into three main phases or categories: bow projections, proto-rams, and three-bladed waterline rams (Fig. 1).

Fig 2. Ship with a spur on a pyxis found in a tomb at Tragana, Pylos dating to 1200–1050 BCE (from Wachsmann 1998, pg. 135).

The development of the ram likely had its origins in the earliest bow projections in the eastern Mediterranean, followed by a few hundred years of various ram innovations or what scholars often refer to as “proto-rams”. This proto-ram period, dating from roughly 850 to 540 BCE, saw the invention of ram-like projections at the warship’s bow, such as bronze coverings, sheathing, boar’s heads, and various ram-like structures lacking three blades. From the 540s BCE and into the early years of the Peloponnesian War (431 to 404 BCE), there was a transition period and introduction of the three-bladed waterline ram.

Fig 3. Drawing of a fully developed cutwater on a warship on a Geometric-era potsherd, ca. 760-735 BCE, Akropolis Museum, Athens (Photo by author).

By the Greek Geometric period (ca. 900 – 700 BCE), the bow projection became a more prominent part of ship design as indicated in early warship depictions. Iconographic evidence shows that during this period warships had acquired a fully developed cutwater (Fig. 3). This cutwater extended the length of the keel past the stem, reinforced the joint between the keel and the stem with a curving timber, and produced a more hydrodynamic bow. There is some debate among scholars as to whether these depictions indicate cutwaters, rams, or both.

Fig 4. Ship on the catchplate of a bronze fibula from Kerameikos Grave 41, ca. 850 BCE (Van Doorninck 1992, pg. 283).

For example, Frederick van Doorninck suggests that the warship on a fibula dated to the 850s BCE indeed indicates a ram (Fig 4). He acknowledges that the existence of a long, massive, and slender bow projection in and of itself should not be the standard for determining what represents a warship ram. However, based on a close examination of the fibula and the stylistic differences between warship representations of the same period, van Doorninck concludes that it is indeed the earliest depiction of a ram.

But if the 850 BCE fibula represents a ram, then it was a highly ineffective ram. These early proto-rams would have been on warships that were still using the laced construction method of shipbuilding. Laced construction is useful at holding the planks of the hull together, though it is unlikely they could maintain the stresses of a ramming attack from a similar ship or ram an opponent successfully. The proto-ram depicted on the fibula must have been a cutwater sheathed in copper or bronze. By the Late Geometric period the Greeks could create copper or bronze sheathing for warships, but there is a lack of evidence of large-scale bronze casting during this period, which means these proto-rams would have been of weaker quality and strength compared to later cast-bronze rams. Therefore, if the proto-ram depicted on the fibula was used as a weapon, then ramming during the 9th century BCE would have been a dangerous affair and likely only done in rare defensive maneuvers.

Fig 7. An example of boar’s head ram on a black-figure vase from Tarquinia, Italy, ca. 525–500 BCE, Museo Archologico Nazionale di Tarquinia (Photo by author).

To judge by the representation of warships found in Neo-Assyrian media, such as a wall painting from Til Barsib and a relief from Kouyunjik, ramming in the 8th and 7th centuries BCE remained problematic (Figs. 5 and 6). Like the 9th century example, the proto-rams in these depictions must have been sheathed or a light cast bronze encasing nailed to the cutwater. They were likely pointed and ended in a single sharp blade or were conical in fashion with a rounded end. These proto-rams would have been ineffective at ramming a warship, even one built in the laced construction method. A pointed ram is meant to penetrate an enemy’s hull, but there is a chance of the attacking ship getting its ram stuck in the opponent. Another factor is the lateral force of ramming a warship broadside or amidships, which could bend or break the ram off the warship entirely. If stuck or broken, the attacking warship would be exposed to boarding or become swamped. As observed by Shelley Wachsmann, when ramming warships still lacked additional strengthening, it was anyone’s guess as to which of the two ships was more likely to sink first. As such, it is likely that these early rams were meant primarily for defensive and only occasionally for offensive attacks.

Fig 8. Modern reconstruction of a three-bladed waterline ram, nicknamed the “DeCasien” naval ram (Photo by author).

It was not until the end of the 7th century BCE that an effective offensive proto-ram was introduced. The first blunt-ended boar’s head rams with their squared off ends are depicted on various painted Greek vases (Fig. 7). The boar’s head ram covers the entirety of the cutwater and terminates in a blunt or bulbous upturned end, counter to the previous pointed ram which ended before the rounding of the stem and culminated with a sharp end. The blunted end of the boar’s head ram made it a more effective ramming weapon as it would be less likely to be lodged in an enemy’s vessel. It also provided penetrative and horizontal damage to the hull planking rather than a piercing hole. The introduction of the boar’s head ram coincided with the transition and use of pegged mortise-and-tenon joinery in shipbuilding in the Aegean.

The combination of extensive use of pegged mortise-and-tenon joinery in ship construction, large-scale lost-wax bronze casting, and the invention of larger warships in the 6th century BCE all led to the introduction of the three-bladed waterline ram. This new ram design could penetrate the hull while separating the planks of the enemy’s warship along the horizontal axis (Fig. 8). The three-bladed waterline ram was first likely used in naval warfare sometime after the 540s BCE and became the standard ram design during the Greco-Persian Wars and into the early years of the Peloponnesian War.