Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

April 2023

Vol. 11, No. 4

The Başbük Rock Wall Panel: Serving Empire, Honoring Syro-Anatolian Gods

By Mehmet Önal , Celal Uludağ, Yusuf Koyuncu and Selim Ferruh Adalı

Authors’ note: A catastrophic earthquake, the epicentre of which was Türkiye’s south-eastern region, took place on 6th February, 2023. The fault line was around 400 km long and it covered eleven cities. The earthquake also impacted Syria and Lebanon. The damage has been extensive. As it took place around 4:00 am in the morning, people were mostly sleeping at their homes. As a result, there was a heavy loss of life. According to official figures – as of the time we present the final draft of this article to ANEToday – the number of losses exceeds 50,000. We express our deep sorrow.

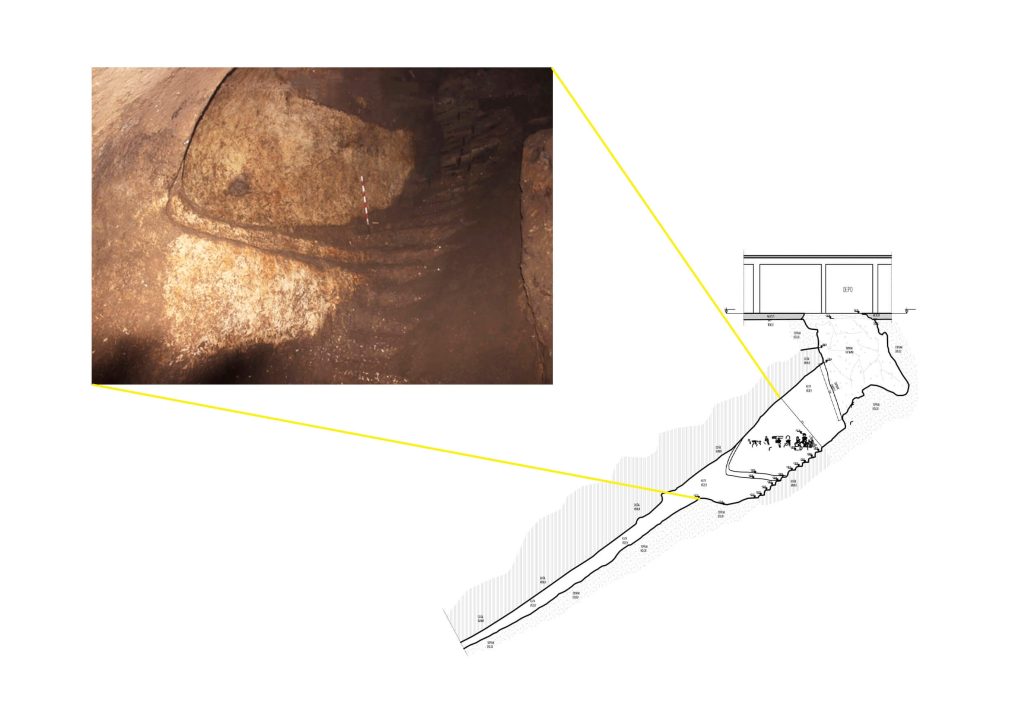

Fig. 1: Ground plan of the subterranean Başbük complex. (Plan by Cevher Mimarlık, based on laser scanning; photograph by C. Uludağ; © Önal et al. 2022)

The discoveries at Başbük, south-eastern Türkiye, attest to a snapshot in history when the Assyrian imperial structure sought to consolidate itself in dialogue with local culture. Başbük is a village near Siverek at Şanlıurfa in south-eastern Türkiye. In 2017, authorities discovered an artificial opening to an underground complex under one of the village’s houses. It had been dug by looters through the house’s ground floor. Following permission and funding from Türkiye’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the rescue excavation took place August – September 2018. Celal Uludağ, Director of the Şanlıurfa Museum, led the effort and the excavations were carried out by Museum archaeologists Yusuf Koyuncu, Aziz Ergin and six workers under the scientific supervision of Mehmet Önal.

The soil’s instability meant that the underground chambers could collapse at any time. The team worked under considerably difficult circumstances. They cleaned the soil and provided an assessment of the chambers. They also recorded the entrance chamber’s rather enigmatic rock panel with incised figures of deities that resemble deities commonly found in Neo-Assyrian art but without fully confirming to all the latter’s details. A further mystifying feature is their accompanying Aramaic inscriptions. More systematic excavations are planned once the site’s security conditions are secured. In 2019, preliminary photographs of the rock panel and its Aramaic inscriptions were sent to and studied by Selim Ferruh Adalı, who joined the team after the excavations. The discovery is reported in the journal Antiquity.

The rock-panel depicts eight figures. The leading figure is placed furthest right. His triple lightening fork and circled star represents the Storm-god tradition of Northern Syria and Southeast Anatolia. Behind his head, his name is written HDD (Fig. 3a), which reveals Hadad, the Aramaic name for the Storm-god. His consort standing behind him is an Ištar-type goddess with her star and polos. On her shoulder is written the name ’TRT (Fig. 3b). The name reads ’Attar‘ata, a West Semitic iteration of Ištar from Syria, attested as ‘Athtart/‘Ashtart from Late Bronze Age Ugarit (Ras Shamra) and Emar (Tell Meskene). Later in history she is known as the famous “Syrian goddess” (Συρία θεά/dea Syria), Atargatis from the Hellenistic/Roman period. Atargatis was read ’Attar‘attē (’TR‘T’) in Hatra and as (A)tar‘ata (ܬܪܥܬܐ) by Bardasian of Edessa.

The goddess ’Attar‘ata is followed by the Moon-God Sîn, a deity also widely worshipped in Harran and its environs. He wears a crescent and full moon crown and a crescent adorns his shoulder. Underneath the crescent is either an archaic sibilant tsade letter or a variant form of a crescent-on-a-pole motif similar to the Aşağı Yarımca stela (cf. Fig. 4; Aşağı Yarımca is near Harran). Sîn is followed by Šamaš the Sun-god with his winged-sun crown.

The figures behind Šamaš remain unidentified. They carry Syro-Anatolian motifs. The fifth figure’s conical headgear and circle crown is similar to that of the Anatolian protector god Karhuha (Fig. 5). One of the goddesses behind this mysterious deity has a headgear similar to goddess Kubaba. Kubaba was a widely worshipped goddess in Anatolia and Syria, and was known as Cybele in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. The procession’s last standing figure bears a polos topped with a double-lined circle. This circle may represent the new moon associated with the Moon-god’s son Nusku, known also as Harranean Sarmas.

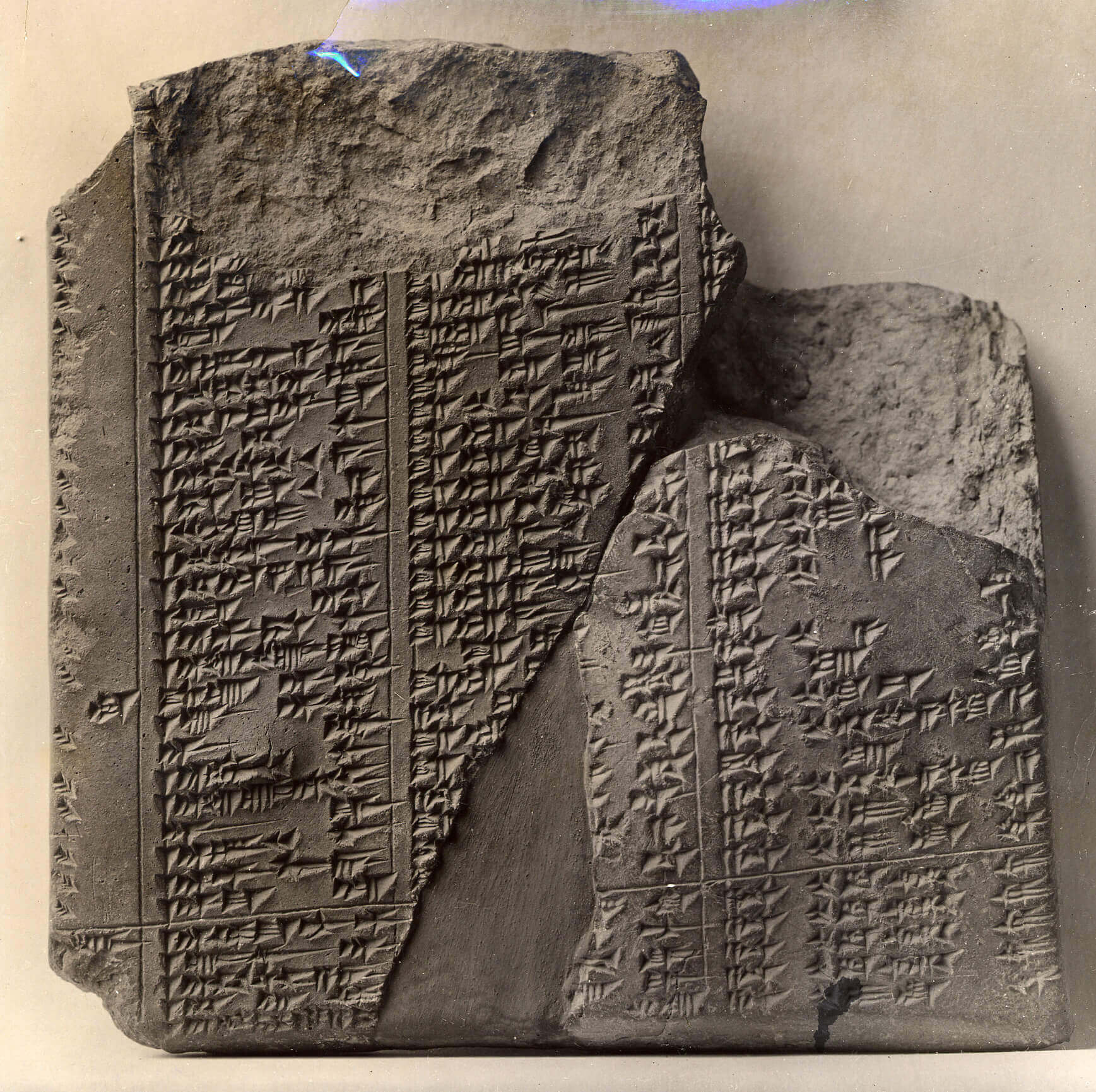

Fig. 6: A clay tablet manuscript containing lines of the Assyrian Eponym List (K 3403). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The short passage inscribed on the rock-panel’s section facing the divine procession’s leader Hadad may contain the name of an Assyrian governor who visited this sacred area: Mukīn-abūa the “head” (re’š) of Tušḫan (MK[N]-’BW[’] R[’]Š TŠḤ[N]; Figure 3d). If the reading is correct, it would point to certain aspects of how Assyrian authorities related to the local community in the Başbük region. Mukīn-abūa is an elusive figure. He is only known from the Assyrian Eponym List where he is designated as the governor of Tušḫan who campaigned against Dēr (Tell Aqar) in 794 BC (Millard 1994: 35). This points to the period of Adad-nirari III (811–783 BC) and supports recent research highlighting Adad-nirari III’s control over his magnates and governors who negotiated with local elements and native cultures. Başbük represents a case where a figure like Mukīn-abūa makes offerings to the deities at Başbük and uses the local leadership title of “head” (re’š). Başbük’s cultic context suggests it was a unique part of the Syro-Anatolian cultural complex and practice which the Assyrians tried to engage so as to exercise their authority. When needed, Mukīn-abūa could be sent to campaign as far south as Dēr.

Başbük’s divine procession uniquely combined different elements. Inscriptions reveal their Aramaic names. Anatolian and Syrian divine motifs as well as their unique features underscore the cult’s local character. Anatomical elements in the depictions, including definition of their muscles, hair and profile point to the early Neo-Assyrian period. The ear-of-corn barley held by the leading Hadad-’Attar‘ata couple and the ear-of-corn imagery on Sîn and Šamaš’s headgears point to the importance of fertility represented in this complex at Başbük. These features differentiate the Başbük rock-panel from other Neo-Assyrian reliefs in the provinces, which in many instances represented sacred or distant spaces reached by an Assyrian king or commander and with art mostly in standardized Neo-Assyrian motifs. Syro-Anatolian motifs, however, are explicitly displayed at Başbük even if the panel was prepared by Assyrian-supported artisans and with Neo-Assyrian techniques. The artisans worked for the Assyrian Empire, but at Başbük they honoured the region’s Syro-Anatolian pantheon.

Mehmet Önal is Professor of Archaeology at Harran University.

Celal Uludağ is Director at Şanlıurfa Archaeological Museum.

Yusuf Koyuncu is Museum Archaeologist at Şanlıurfa Archaeological Museum.

Selim F. Adalı is Associate Professor of Ancient History at Social Sciences University of Ankara

The authors are grateful to Kemalettin Köroğlu and J. David Hawkins for permission to share their drawings.

Further Reading:

Hawkins, J. D. 1972. “Building inscriptions of Carchemish: the long wall of sculpture and great staircase”. Anatolian Studies 22: 87–114.

Köroğlu, K. 2018. “Neo-Assyrian rock reliefs and stelae in Anatolia.” In K. Köroğlu and S. F. Adalı (ed.) The Assyrians: Kingdom of the God Aššur from Tigris to Taurus. İstanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları: 162–207.

Millard, A. R. 1994. The Eponyms of the Assyrian Empire 910–612 BC. Helsinki: The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project.

Önal, M., Uludağ, C., Koyuncu, Y. and Adalı, S. F. 2022. “An Assyrianised rock wall panel with figures at Başbük in south-eastern Turkey”. Antiquity 96 (387): 575–591.

Osborne, J.F. 2021. The Syro-Anatolian City-States: An Iron Age Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Siddall, L. R. 2013. The Reign of Adad-nırār̄ı̄ III: An Historical and Ideological Analysis of an Assyrian King and his Times. Leiden: Brill.

Want To Learn More?

Rock Art in Central Sahara: From Analogue to Digital

Rock Art in Central Sahara: From Analogue to Digital

By Savino di Lernia

There are hundreds of thousands of examples of rock art in the Sahara, dating from the present back to over 10,000 years ago. But with access currently difficult thanks to unrest, digital archives offer new opportunities. Read More

The Neo-Assyrian Empire and Egypt

By Mattias Karlsson

The Neo-Assyrian and Egyptian Empires were bitter rivals in the first millennium BCE. But despite its size and antiquity, Egypt was simply another conquest added to Assyria’s multicultural empire. Read More

Divine Channels: Rediscovering the Canal Networks of the Assyrian Empire

By John MacGinnis, Daniele Morandi Bonacossi, and Jason Ur

Today northern Iraq is a land of rolling plains and a few rivers. But Assyrian kings cut immense canals into the landscape for irrigation and transportation. Read More