Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

January 2023

Vol. 11, No. 1

Putting the Luwian Culture on the Map

By Eberhard Zangger and Serdal Mutlu

Troy stands out in the popular imagination thanks to Homer’s Iliad. However, in archaeological terms Troy may seem like an isolated outpost in the northeastern Aegean at a time when the cultural powerhouses were far to the south, in the Mycenaean and Minoan cultures. But Troy was hardly alone; who were its neighbors?

What was the nature of the Anatolian side of the Aegean during the Middle and Late Bronze Age (c. 2000–1200 BCE)? Did it have an independent culture or was it an economic and political wilderness? These are some of the questions addressed by our recent study of Middle and Late Bronze Age Western Anatolia. And what is the role of the still not fully understood Luwian culture?

“Not too much data” would be an apt paraphrase of the current state of knowledge regarding the Middle and Late Bronze Ages of western Asia Minor, a parochial opinion due in part to an almost complete lack of excavations by archaeologists from outside Turkey. But an international team consisting of archaeologists, geoarchaeologists, and global information system (GIS) experts set out to evaluate the archaeological excavations and surface surveys conducted in western Turkey to date, insofar as they recorded settlements from the second millennium BCE. Work on this project began in 2010. Now, in 2022, the project culminates with the publication of the final report.

What actually did the project entail? By assessing the results of 33 excavations and 30 surveys, the team produced a meta-analysis including a catalog comprising 477 large settlement sites (diameter of >100 m) that were inhabited throughout the second millennium BCE.

Virtually all of the field projects taken into account were conducted by Turkish archaeologists, whose preliminary reports were mostly in Turkish. Each site that was catalogued has a local name and geographic coordinates; each is mentioned in the archaeological literature as possessing Middle and Late Bronze Age ceramic assemblages; each is also indicated on a foldable map that accompanies the publication, and for each site 30 physio-geographic parameters were determined to be analyzed using GIS.

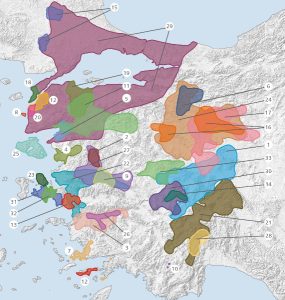

Topographic map indicating the situation around 1200 BCE, using geographic coordinates of all 477 settlements sites.

The collated data confirms the existence of an independent Luwian culture between Mycenaean Greece in the west and the Hittite kingdom in Central Asia Minor in the east. The Luwian culture even covered a larger area and endured much longer than its better-studied neighbors. One of its potentially identity-forming features was the Luwian language, which seems to have been dominant throughout most of western and south-central Asia Minor during the second millennium BCE.

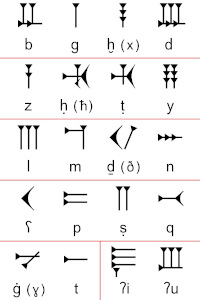

What is more, the Luwians had developed a hieroglyphic script, which came into use as much as 500 years before the nearby Mycenaean Greeks first acquired writing skills. Moreover, Luwian hieroglyphic remained in use even after the demise of the Bronze Age cultures around 1200 BCE and throughout the Dark Ages until ca. 700 BCE. During this same period people in Greece lost their knowledge of writing for as much as 400 years.

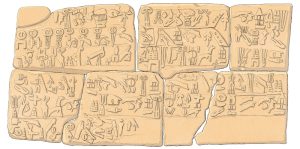

Luwian hieroglyphic inscription (4 m wide) from reign of King Šuppiluliuma indicating that the Lukka in southwest Anatolia were causing trouble (after J. David Hawkins 1995).

The number of Luwian settlement sites we know already exceeds the number of sites from all the culture’s well-investigated neighbors combined. A Luwian king corresponded with the Egyptian pharaoh whereas, as far as we know, Mycenaean kings never did. Recognizing a distinct Luwian culture also provides a context for the rise of the later Lycian, Lydian, and Carian cultures in western Asia Minor, whose languages turn out merely to be Luwian dialects. Evidently, the Late Bronze Age Luwian culture provided the substrate for later Early Iron Age cultures to thrive.

If this reconstruction is correct, then new questions arise: Who exactly were these Luwians? What distinguishes their culture from those of their neighbors? And why did it take so long for the Luwian culture to be recognized?

To this day, the Turkish landscape has not been urbanized. People still live concentrated in very specific places.

Owing to the large number of recorded settlement sites, most of which are exceedingly well preserved, it is possible to reconstruct the economic system of the time. People lived in densely packed settlements that were usually several kilometers apart, leaving the landscape in between uninhabited. Sites along the edges of the fertile floodplains, which are much larger in western Asia Minor than in Greece, were clearly favored. Farmers lived next to their farmland in places where abundant fresh water was available. Occasionally, the leaders had fortifications with mighty walls built on hilltops near thoroughfares of strategic importance. It is not yet clear whether these citadels were garrisons, arsenals or refuges for the local population. Central places with the seat of a local ruler have thus far not been excavated, and as a consequence no written archives have been discovered. Including the potential road network in the GIS analysis revealed that 250 settlements were located less than four kilometers from strategic routes.

A good fifty percent of the area west of an imaginary north-south line from Eskişehir to Antalya has been systematically screened in recent decades by archaeological surface surveys. It is impossible to say whether the areas that have not yet been surveyed were equally densely populated; extensive forests may also have existed at the time. All recorded settlement sites were inhabited for at least a thousand years; however, many lasted for a full 5,000 years. Although the economic system was multifaceted, it was exceptionally durable. In addition to subsistence agriculture, each site appears to have produced one or two other goods, such as ores, fabrics, or pottery. Caravans would have brought surplus commodities to a central location, including those on the coast, from which goods could then be traded across long distances.

Fishing villages lined the coast between coastal hubs that benefitted from particularly advantageous natural harbors. A third category of sites on the coast were ports of call established by foreigners, preferably in hide-aways that were difficult to access from the interior of the country. Mycenaean Greeks apparently maintained such a port at Müsgebi, near present-day Bodrum. These ports of call were obviously known and tolerated by locals. This also suggests that the Luwians maintained ports of call abroad.

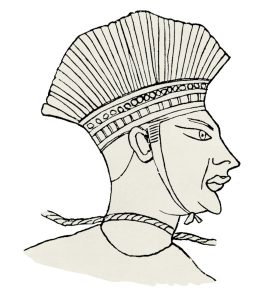

The reverse side of the Mycenaean warrior vase shows advancing warriors with lifted spears, feather crowns and round shields (after Furtwängler and Loeschke, Mykenische Vasen).

What did the Luwians look like? A distinctive feature of Luwian warriors seems to have been feather crowns. Grim attackers with such peculiar headdresses appear on decorations of pots from Luwian lands, but also on the back of the famous Mycenaean warrior vase which apparently shows the enemies of the Greeks in the Trojan War. Also, in the mortuary temple of Ramses III with its famous Sea Peoples inscriptions, feather crowns are the most conspicuous feature of the attacking Sea Peoples. This is a hint that both the Mycenaeans in the Trojan War and the Egyptians defending themselves from the Sea Peoples may have fought the same enemy, i.e., Luwians from western Asia Minor.

Line drawing of a feather crown warrior from the mortuary temple of Ramesses III showing the most distinct feature of the Sea Peoples.

Politically, the Luwian lands formed a patchwork of states and petty kingdoms that at times competed with one another, but also repeatedly entered into alliances, primarily for military purposes. Troy was a border town facing Thrace, a region with cultures clearly different from the Luwian. In the thirteenth century BCE, Troy evolved into a hub for long-distance trade, especially with Cyprus and Syria.

How is it possible that this Luwian culture had not been identified earlier, if it covered such a large region and thrived for so long? An answer appears to lie in the political interests of the early twentieth century. In the 1920s, Arthur Evans, the excavator of Knossos, with his book series The Palace of Minos at Knossos, laid the theoretical foundation for the Aegean Bronze Age. In doing so, he identified only cultures which were on European territory, in part it seems because a war was raging between Greece and the collapsing Ottoman Empire and Evans was not interested in directing research interest towards cultures in what he considered to be “barbarian” territory.

Troy may be more famous than any other archaeological site in the world, but it is on Turkish soil. Evans was keen to portray Crete as the cradle of European culture and the forerunner of modern Western society, a conviction he developed even before his excavations on Crete had begun. The modern myth of European origins of the Bronze Age Aegean, which Evans fabricated, required downplaying potential Asian influences. Most scholars agreed with this approach because it was conducive to European nationalist and colonialist goals.

Regrettably, the patterns of thought established by Evans—and the associated rhetoric—have never been fully corrected. As far as the second millennium BCE is concerned, European scholars have by and large focused their interest on Crete and the southern Greek mainland, while relations with Anatolia have so far remained mostly neglected. As a result, the now identified Luwian culture offers enormous opportunities for exciting discoveries by present and future generations of archaeologists.

Eberhard Zangger is a geoarchaeologist and president of the Luwian Studies foundation in Zurich, Switzerland.

Serdal Mutlu is an archaeologist with a degree from Selçuk University in Konya.

This project was funded by Luwian Studies and a grant from the University of Zurich.

Further reading:

Eberhard Zangger, Alper Aşınmaz, and Serdal Mutlu (2022): “Middle and Late Bronze Age Western Asia Minor: A Status Report.” In: The Political Geography of Western Anatolia in the Late Bronze Age, edited by Ivo Hajnal, Eberhard Zangger, and Jorrit Kelder, pp. 39–180. Archaeolingua, Budapest.

Who were the Luwians? (in German). Archaeologie Online.

Want To Learn More?

The Symbolic Representation of the Cosmos in the Hittite Rock Sanctuary of Yazılıkaya

By Eberhard Zangger and E.C. Krupp

The Hittite sanctuary at Yazılıkaya functioned as a calendar. But the carefully carved galleries of gods and goddesses depicted much more, a representation of the cosmos moving through time. Read More

A Great King and a Wanax? The Politics of Mycenaean Greece

A Great King and a Wanax? The Politics of Mycenaean Greece

By Jorrit Kelder

Empires like the Egyptians, Hittites, and Babylonians dominated the Late Bronze Age. But what was happening to the west? Read More

The Social Context of Writing in Ancient Ugarit

By Philip Boyes

Writing creates physical objects using communications systems. But it is also a social act. What does the multiplicity of languages at the Late Bronze Age site of Ugarit tell us about people and identities? Read More