October 2018

Vol. 6, No. 10

The Upper Tigris and the Ilısu Dam

By Anthony Comfort and Michał Marciak

Many areas of the Near East are under threat from development projects, but in some the peril is more immediate. Our book How Did the Persian King of Kings Get his Wine? The Upper Tigris in Antiquity (c.700 BCE to 636 CE) was recently published, the culmination of several years’ research and various visits to South-East Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan.

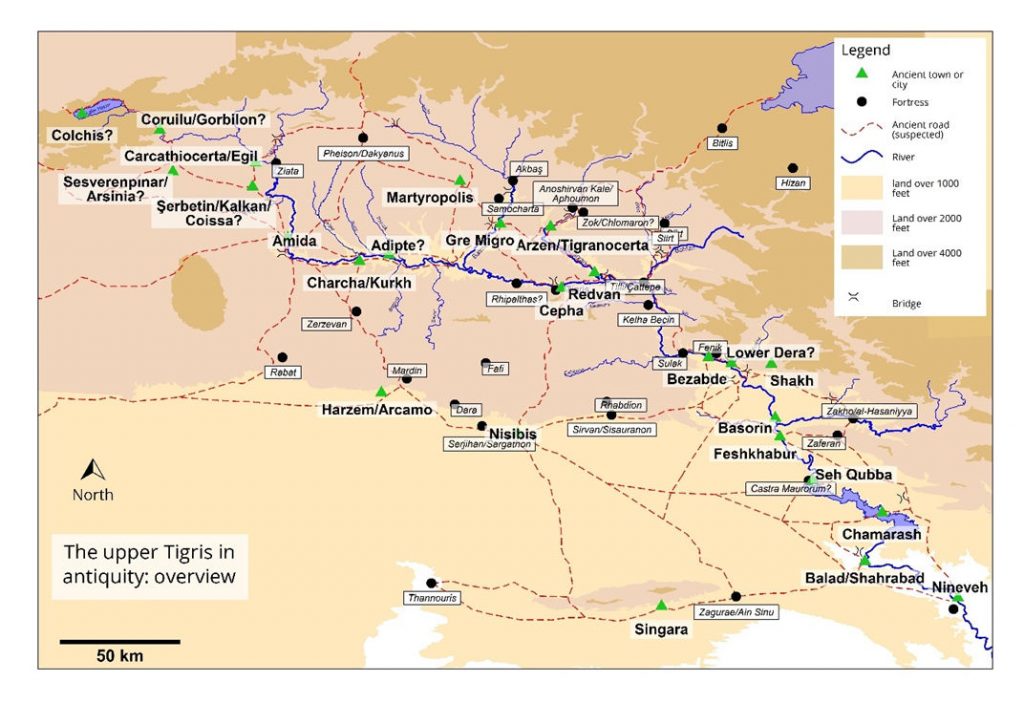

Map showing survey area and sites mentioned in the text. Courtesy Anthony Comfort.

Map showing survey area and sites mentioned in the text. Courtesy Anthony Comfort.

The Tigris valley north-west of Cizre. Photo by Anthony Comfort, 2007.

The Tigris valley north-west of Cizre. Photo by Anthony Comfort, 2007.

The area is notoriously difficult for historians and archaeologists who wish to study it because of the security situation, in particular the long-running conflict between the PKK and the Turkish security forces. This area, just beyond the northern border of Assyria, was a very important crossroads from the Iron Age through the modern period.

The upper Tigris is also the location for various dam projects, in particular the Eski Mosul Dam in northern Iraq, completed in 1986, and the Ilısu Dam in Turkey. The latter has aroused much controversy and was completed only in the spring of this year. It is thought that the reservoir behind the dam is currently being filled. It will thus be in the process of destroying much of the well-known multi-period site at Hasankeyf, but also many other sites along 136 kilometers of the Tigris valley.

This valley (and much of the upper Euphrates valley too) was surveyed in part by a team led by Guillermo Algaze in the 1980s. However, he was unable to visit all of the reservoir area; his final report was never completed because of problems in viewing the ceramics collected by the team; and most of what he saw on the surface has remained unexcavated, despite the very great interest of the valley for the history and archaeology of the Near East. Most of this will now be lost.

Apart from the loss of many Kurdish villages and the damage to the flora and fauna resulting from the creation of the Ilısu Dam, the inundation of this part of the Tigris constitutes a grave and irreversible loss to global cultural heritage. This valley – and those of the tributaries affected by the reservoir now being created – is of especial interest to those interested in Assyria and its relations with Urartu, in the Achaemenid and Hellenistic periods (and especially in the ‘March of the Ten Thousand’ recounted by Xenophon), in the establishment of Rome’s eastern frontier and in its relations firstly with the Parthians and then the Sassanian Persians, in late antiquity and the origins of Christianity in the Aramaic or Syriac-speaking communities, many of which lasted in this region until after the First World War – with some groups holding on even now, especially in the Tur Abdin and the area east of Mosul.

Our book provides an overview of the history of the region between the zenith of the late Assyrian empire around 700 BCE and the arrival of the Arab armies that conquered Sassanian Persia at the battle of Qadissiyah in 636 CE. It examines the importance of the valley for transport and communications, both along the river itself but also through a road network for which remains of several ancient bridges provide good evidence. The book also briefly examines the damage caused by dam construction, and a link to the publisher’s site allows those interested to view the archaeology sections of the ‘Environmental Impact Statement’ created for the Ilısu Dam.)

The ancient bridge on the Garzan river at Şeyhosel. Photo by Anthony Comfort.

The ancient bridge on the Garzan river at Şeyhosel. Photo by Anthony Comfort.

The ancient bridge on the Batman Su (Harap). Photo by Anthony Comfort.

The ancient bridge on the Batman Su (Harap). Photo by Anthony Comfort.

The valley and its surroundings are particularly rich in ancient rock reliefs. Those dating from the period reviewed are discussed and presented.

Parthian horseman near Cizre. Photo by Anthony Comfort.

Parthian horseman near Cizre. Photo by Anthony Comfort.

Sassanian (?) horseman, Boşat. Photo by Anthony Comfort.

Sassanian (?) horseman, Boşat. Photo by Anthony Comfort.

A series of specially drawn maps is included in the text. The major section of the book is however the final catalogue, which presents sites along the valley. In many cases these are hardly known to the world of scholarship despite their great importance for the history of the entire Near East.

They include Hasankeyf, of course, which was base of a Roman Legion in the third and fourth centuries CE and capital of the district of Arzanene; but also Tigranokerta (the capital of the short-lived Armenian empire created by Tigranes II, thought to be located at Arzen); Amida (now Diyarbakır), the capital of the Roman province of Mesopotamia after the surrender of Nisibis to the Persians in 363CE; Tilli/Çattepe, an important river port at the confluence with the Bohtan river where the Tigris turns south and passes through magnificent gorges (and now the Ilısu Dam), before emerging onto the plains of Mesopotamia near the remarkable and unexcavated fortified twin sites of Bezabde/Phaenica (Fenik).

The ancient bridge at Hasankeyf in 2005. Photo by Anthony Comfort.

The ancient bridge at Hasankeyf in 2005. Photo by Anthony Comfort.

Arzen/Tigranokerta. Photo by Anthony Comfort, 2007.

Arzen/Tigranokerta. Photo by Anthony Comfort, 2007.

Phaenoica/Finik. Photo by Anthony Comfort, 2006.

Phaenoica/Finik. Photo by Anthony Comfort, 2006.

The walls of Amida (Diyarbakır). Photo by Michał Marciak.

The walls of Amida (Diyarbakır). Photo by Michał Marciak.

The catalogue travels south/north and starts with the twin cities of Mosul/Nineveh. It provides many images from recent satellite imagery to illustrate the sites along and around the valley, some of which have hardly been visited at all by archaeologists. These include Zaferan, visited by Gertrude Bell and one of a very few known fortified sites from the sixth century CE; Shakh, east of Cizre, which may be one of the three cities of Gordyene mentioned by Strabo and which has Assyrian reliefs and ancient fortifications including – possibly – a Roman winter camp used by Lucullus in 64 BCE; it also seems to have been a summer hill resort used by at least one Sassanian king. The book also examines crossing points of the Tigris north of Mosul and discusses the location of ‘Castra Maurorum’, one of the major fortresses handed to the Persians after the death of the emperor Julian in 363 CE.

The discussion of Nineveh and the origins of Mosul is accompanied by a description of the early monasteries of the area, several of which were founded during the period reviewed in the book. Although Nineveh was sacked during the fall of the Assyrian Empire in 612 BCE, neighbouring Mosul seems to have regained the position of pre-eminent city of the region, possibly even before its refoundation by the Arabs. It has never lost this position since.

We are aware of the preliminary nature of much of our own work in the area. It is of course highly desirable that others should be able to continue this research as soon as possible. Sadly, the completion of the Ilısu Dam has shut off a large area and destroyed various important sites, but there are many others that need urgent study before more damage is inflicted. In Iraqi Kurdistan, survey work and some excavation is still possible and a current project is examining the site of the battle of Gaugamela. Archaeological and historical work has begun in this special and beautiful region but much remains untouched.

Anthony Comfort is an associate member of the Centre for the study of Greek and Roman Antiquity at Corpus Christi College, University of Oxford.

Michał Marciak is an Assistant Professor at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków.

Parthian horseman near Cizre. Photo by Anthony Comfort.

Parthian horseman near Cizre. Photo by Anthony Comfort.

The walls of Amida (Diyarbakır). Photo by Michał Marciak.

The walls of Amida (Diyarbakır). Photo by Michał Marciak.