July 2018

Vol. 6, No. 7

Sinai’s Unfinished 150-year Survey

By Ahmed Shams

The year 1868-1869 CE was an important one for the study of the Sinai Peninsula. That year two British Royal Engineers, Captains Charles W. Wilson and Henry S. Palmer, several non-commissioned officers, in addition to an Arabic linguist and orientalist, an Egyptologist, photographer, natural historian, and others, conducted the first Ordnance Survey for Sinai Peninsula. Although pilgrims, travelers and scholars had visited the vicinity of Mount Sinai since the 4th century CE, this was the first-ever scientific party to undertake the cartographic mapping of Biblical Sinai. But the job of mapping the Sinai is still unfinished.

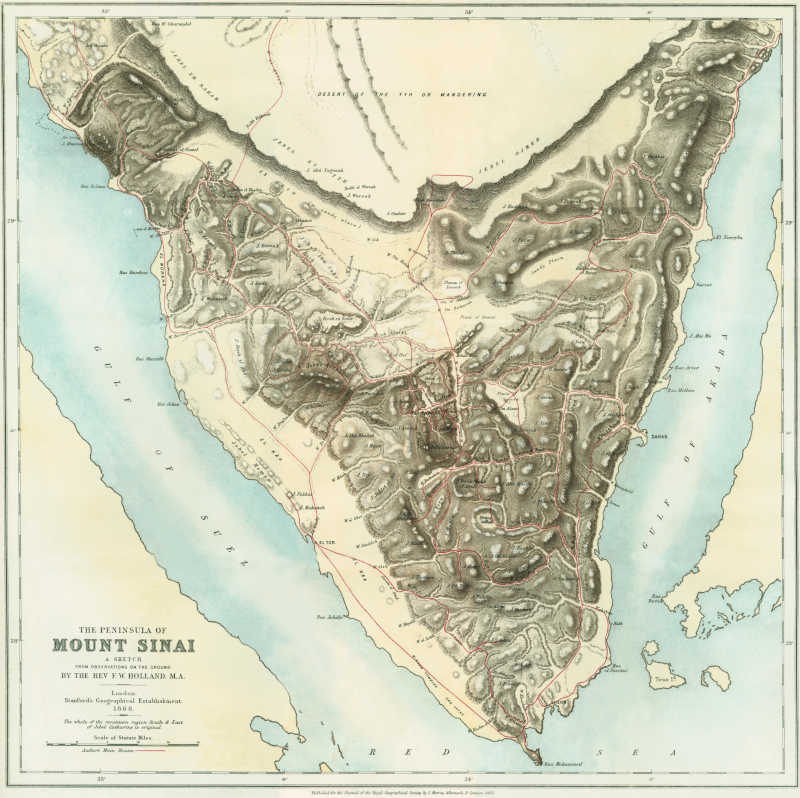

The British survey followed in the footsteps of Europe’s cartographic bias towards Southern Sinai – the presumed location of Biblical Mount Sinai –that had existed since at least 16th century CE. But it also marked an important transition, from what might be called individuality to institutionalization in mapping and mapmaking of the peninsula. Prior to the Ordnance Survey, all the maps for the Sinai were non-survey sketch maps, whether based on armchair cartography, ground observations, or both. One such sketch map in particular laid the foundation for the Ordnance Survey, namely, the 1868 CE “The Peninsula of Mount Sinai: A Sketch from the Observations on Ground” map by Frederick Holland, who later joined the British Royal Engineers.

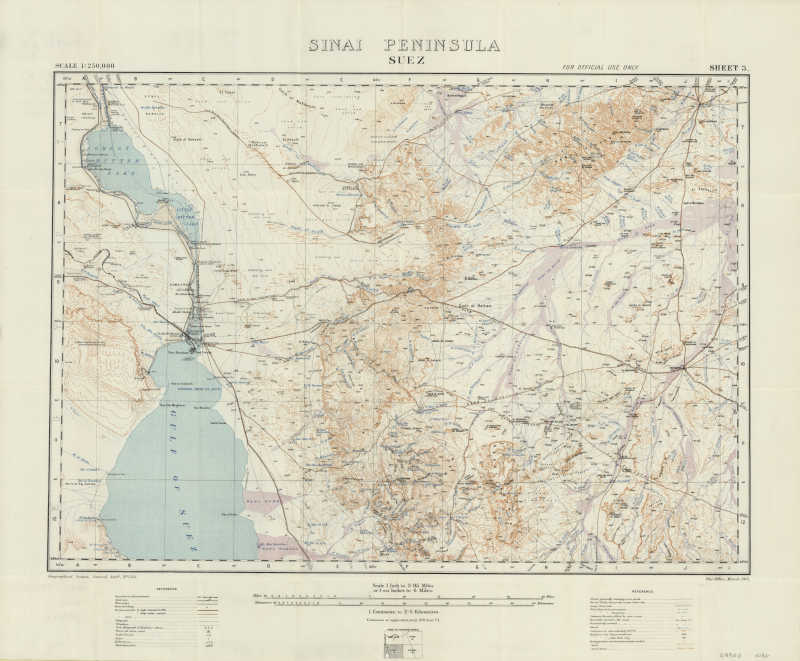

International geopolitics was the driver of 19th and 20th century mapping. A standoff between the British, who effectively controlled Egypt from 1882 onward, and the Ottoman Empire, ended with the Taba border crisis in 1906 and created the eastern border of the Sinai. The events of World War I led to a transformation in mapping and mapmaking bias from the historic south to the geo-political north, which remained a battlefield throughout the century. Two aspects of mapping in that era are outstanding. One is the contribution of Leonard Woolley and T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia), who did a survey of the northeastern Sinai and Negev on behalf of British Military Intelligence just prior to the war under the guise of searching for the Biblical ‘Wilderness of Zin.’ The other is the growing role of aerial photography in creating and checking topographic maps.

Authorities from different countries, including Egypt, Israel, the former Soviet Union and United States, as well as scholars, assumed Sinai’s survey is a finished project. This was partially true when it came to place names, which were mostly compiled from the Anglo-Egyptian 1:100,000 Sinai Peninsula topographic map-series produced in mid 1930s-1940s. That map-series remained the definitive source for Sinai’s Gazetteer until 1980s and beyond. Compiling new maps from aerial photography and satellite imagery and older British maps reinforced that perception. The new maps showed more detailed topographic features (contours), while the level of details of the cartographic features (data) did not necessarily improve, with exception of specific areas of high military or economic interest, such as minerals, oil and gas. But is this perception true? Is the mapping of the Sinai essentially complete?

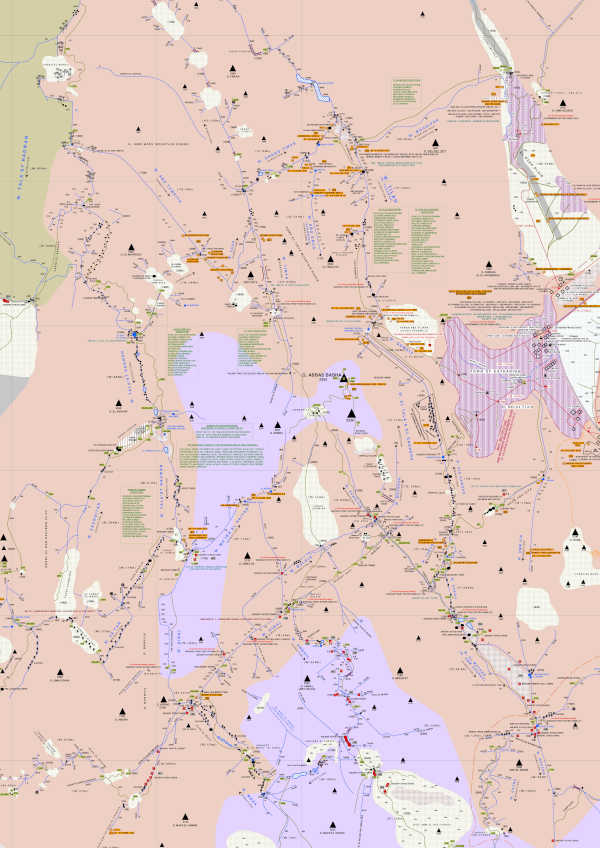

To challenge this the Sinai Peninsula Research (SPR) was founded in 2000 as a private field survey to study the mapping and mapmaking patterns and cartographic knowledge of the peninsula. The results were dramatic. The SPR discovered significant loss of cartographic knowledge on the historic and contemporary maps – information, especially place names, were being removed and lost to scholars. In its field work the SPR survey also reintroduced 19th century practices as the only means to recover the loss of cartographic data, place names plus points of interest. For example, none of the recent large or small scale maps by different survey authorities assigned more than 100 place names in the High Mountains of Sinai Peninsula, while the SPR maps assigned 475 place names.

There has been a 150-years gap in mapping and mapmaking in Sinai Peninsula. This has had a considerable impact on understanding tribal territories, development projects, administrative boundaries and governance, and archaeological surveys. Paradoxically, the institutional resources invested by different survey authorities over this period did not lead to a significant improvement in cartographic data in the second half of 20th century; instead, it led to the deterioration in several areas. These losses have unique impacts across the peninsula and beyond.

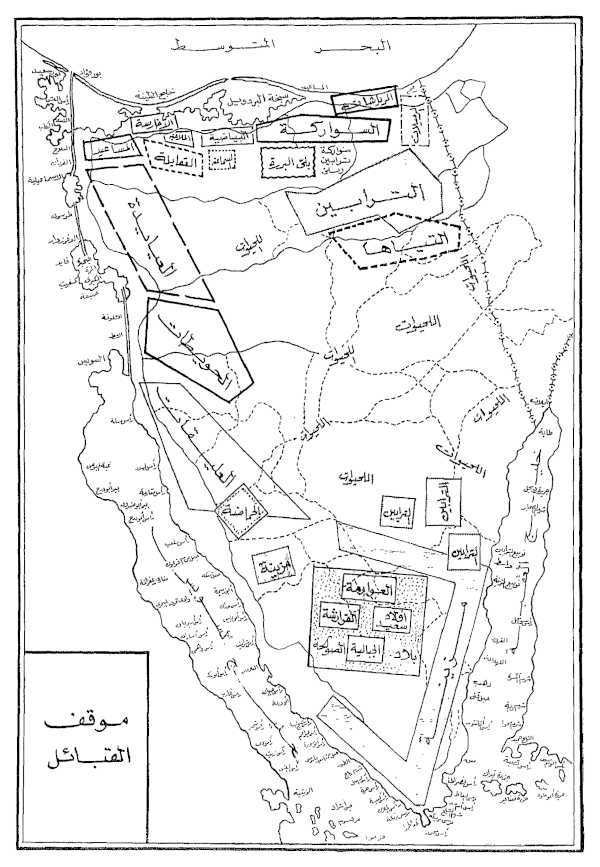

For cultural geographers like Doreen Massey, place is “the meeting up of histories in space.” It is through place names that Bedouins claim their tribal territories and identify their boundaries. These might reflect traditional mutually recognized ownership of orchards, water wells, conduits, cisterns and reservoirs by an individual or a family, or shared tribal utilization of water resources, pasture, temporary campsites or quarries. The young semi-urbanized 21st century Bedouin do not traverse the land extensively like their ancestors to learn about place names and tribal claims to local resources through a long-standing oral tradition. Moreover, those places are not assigned on maps as names or points of interest. That loss has resulted questions about place names which were lost or altered, and will cause counter tribal claims and local disputes in the future.

Cartographers do not transliterate or transcribe place names on maps in their tribal dialect of origin. Cartography standardizes how place names are written on maps as an institutional practice governed by international organizations (such as the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names) and national survey authorities. Sinai has eight Bedouin dialect groups; institutional mapping and mapmaking neglected the importance of transcribing place names in their dialect of origin, or to assign Bedouin land use and resources utilization to identify tribal territories. To do so would have required different Bedouin guides originated from each surveyed tribal territory.

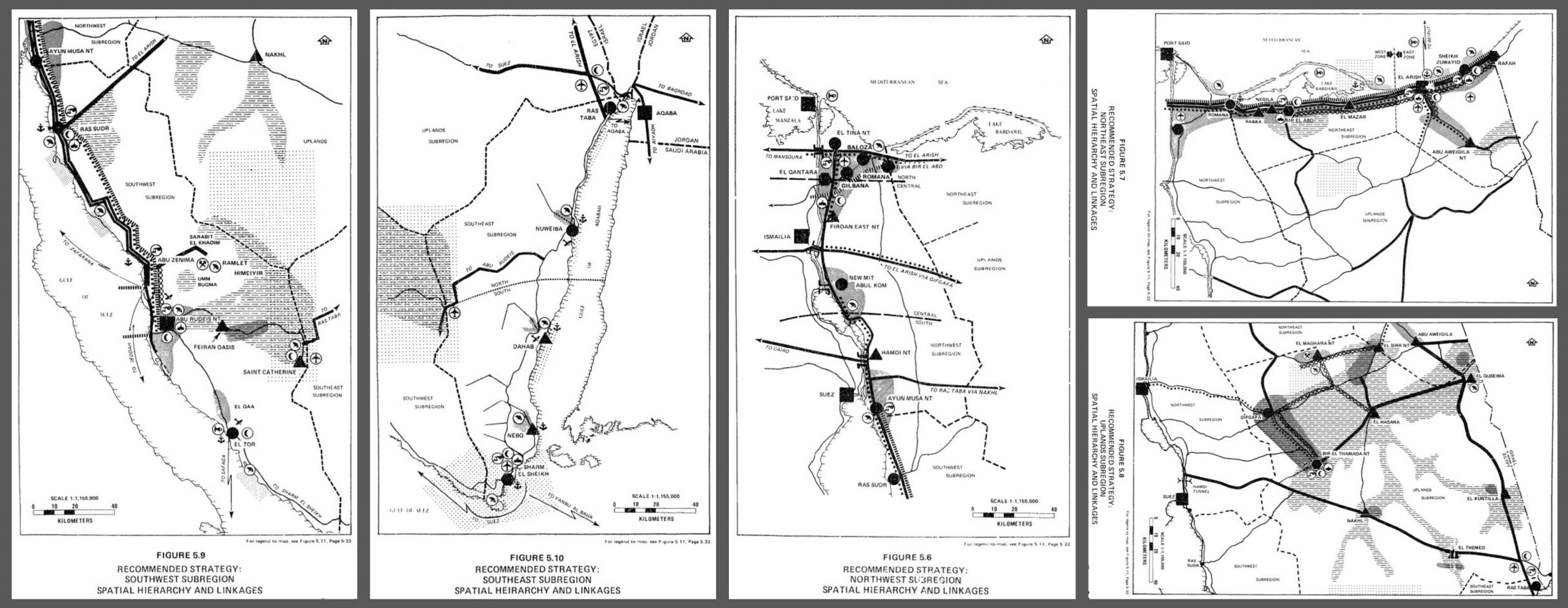

For development planners, place is “where resources exist in landscapes,” and place names and/or points of interest are how development organizations realize the distribution pattern of resources. But only strategic resources are assigned on the large or small-scale maps of the Sinai Peninsula. In addition, only land tenure inside urban boundaries are registered and/or assigned on maps, with some exceptions in remote valleys and mountains. The limited availability of inland cartographic data and the concentration of projects on the coasts of the peninsula helped cause the depopulation of inland Bedouin localities and multilevel development deficiencies.

Place names and points of interest have direct impact on both Bedouins and planners in the peninsula and on the functionality of administrative boundaries. Essentially, a map is the tool to communicate places between parties. A map in this sense informs the realities on ground through cartographic data. The division of Sinai’s administrative map into polygon-shaped municipalities complies with neither local patterns of place names and points of interest, nor with physical geography, or even with local development policy.

For archaeologists, the data provided by cultural geographers and Bedouins serves to locate ancient sites on the landscape and to contextualize ethnoarchaeology, while for planners these data are necessary for site management. Overlooking place names or their meanings contributes to the misinterpretation of local histories or overlooking entire sites. For example, the SPR survey re-discovered the only ‘Qanat’ water system in the Sinai, providing a key link for understanding the diffusion of tunnel-well irrigation systems between the Near East and North Africa.

The site name Deir Fukarra clearly refers to an existing fuqara (called foggara in North Africa). And despite the fact that the name was given to the neighboring excavated site, previous archaeological or cartographic surveys did not mention an existing tunnel-wells system in the vicinity with exception to several conduits. Indirectly, the foggara was identified by place name on survey maps before being investigated and assigned on the SPR maps. Ground truthing a place name revealed an entirely new aspect of cultural history.

Filling the 150-year gap in mapping and mapmaking in Sinai Peninsula and the Middle East by the SPR survey reveals how the peninsula’s maps and history were not well-defined by cartographic data, and did not fully reflecting the local realities on ground. Ultimately, is time for “A New Sinai Map.”

Ahmed Shams teaches International Cultural Heritage Management at Durham University. He is the founder of Sinai Peninsula Research (SPR).