Magnetometry in the Erbil Plain

Lonnie Reid, 2024 Fieldwork Scholarship Recipient.

My name is Lonnie Reid and thanks to ASOR’s scholarship, I had the opportunity to go to the Kurdistan Region of Iraq as a part of the Rural Landscapes of Iron Age Mesopotamia Project (RLIIM), run by Dr. Petra Creamer. For my report, instead focusing just on a specific trench, as we had multiple open this season, I will talk mainly about our main survey method, magnetometry.

But before we jump in, Qach Rresh is a Neo-Assyrian site in the Erbil plain that appears to be a transition center for goods going in and out of the major nearby city. Due to this, there are items of everyday transport on site such as pottery and arrowheads, and some things that you wouldn’t see everyday, but that’s a topic for another time.

A magnetometer is a survey device that senses the slight magnetic changes in the atmosphere using the poles on either side of the device. The poles sense magnetic fields for about a meter in every direction. The device is so sensitive that the person operating it cannot wear any amount of magnetic clothing or have electronic devices on them. So sadly, while we were marching up and down rows of wheat for an hour or two at a time, we couldn’t have music or a podcast going.

A magnetometer works by taking a reading of the magnetic field every second. So to keep the readings from overlapping, we would have to walk at a constant pace of a meter per second, up and down a tape measure grid, so that we would know we are walking straight and at pace at all times. Funnily enough, the technology for magnetometers has remained fairly consistent over the years, meaning it’s old, so there’s a bit of manual adjusting we had to do before every use. The poles that measure magnetism can come off for easier transportation, meaning that we had to level them before each use to make sure that the poles were reading at the same height. Also to make sure the readings are stable, we had to hold the magnetometer out in front of us, which was also just as draining as walking. It appears light as parts are made of PVC material, but I promise, balancing those sensors on the sides is no joke.

The magnetometry team was always comprised of three people, one person holding the device and walking, and the other two would set up and move the grid system, so that as soon as one twenty by twenty square block was done, another could immediately start. I think the record for the most blocks done in a day was 16. Once you get into a groove, it’s pretty zen. But as I mentioned before, the lack of music does make it a long endeavor.

But why is magnetometry important? It’s a non-destructive survey method that allows archaeologists to plan out where they want to set up trenches, without needing to make an initial trench. This allows for areas with potential interest to be found sooner than just by choosing a spot based on the topsoil or by location near previous trenches.

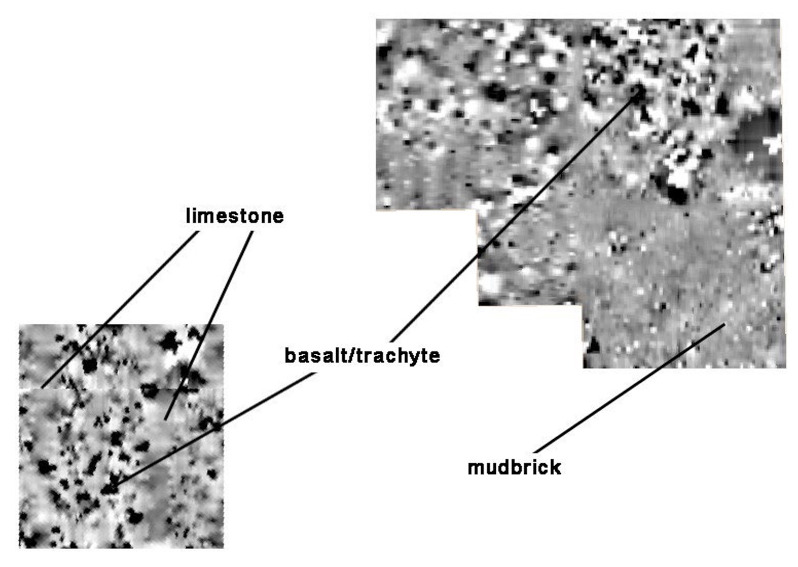

Finally, I mentioned that the magnetometer has not really had a technological update in a few decades, so how do we process the data? Well the magnetometer itself does not know where it is within space, so that’s why we have to time out our steps at a meter per second. The machine does know that we walk up and down a grid in a zigzag pattern and whichever direction we face to begin with, must be the same direction for all of the squares to keep the data consistent. When uploading the raw data to the computer, it comes out as pixels, some shade of grey between black and white. The more white an area is, the more magnetic it is and the darker an area is, the less magnetic it is. Different types of stones and other materials will have their own magnetic signature. For example, basalt shows up black as it has little magnetism, whereas limestone is a medium gray, but mudbrick appears white. So eventually, you get a magnetic map of the area that shows where potential buildings used to lie due to the magnetic presence of the building materials.

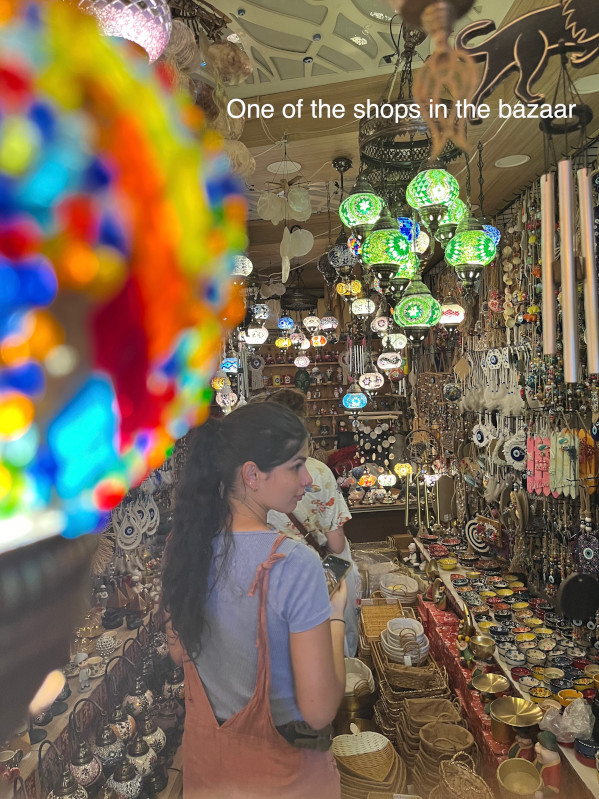

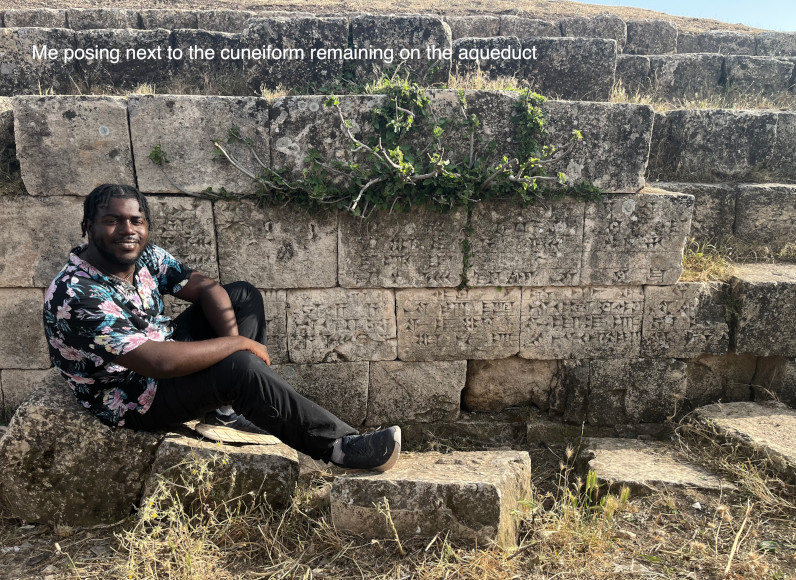

Magnetometry might have been the most intensive yet fun part of my fieldwork this past summer. But the trip wasn’t just all digging and marching. On the weekends we would make day trips to other archaeological sites in the greater Erbil area, and mingle with some of the locals and friends of the project. Our adventures included visiting Shanidar Cave, the bazaar, and a still standing aqueduct in Jerwan.

Lonnie Reid is a recent graduate of Emory University who studied math and art history. Currently a high school math teacher at Rabun Gap-Nacoochee School, Lonnie enjoys using both sides of his brain, and hopes to be able to discover more in the field for years to come.

Latest Posts from @ASORResearch

Stay updated with the latest insights, photos, and news by following us on Instagram!

American Society of Overseas Research

The James F. Strange Center

209 Commerce Street

Alexandria, VA 22314

E-mail: info@asor.org

© 2025 ASOR

All rights reserved.

Images licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License