Table of Contents for Bulletin of ASOR 393 (May 2025)

Pp. 1-22: “Nabatean Tent Sites on the Ruhot Plain, Central Negev, and Nomadic Visibility,” by Maayan Margulis and Steven A Rosen

Nabatean campsites, reflecting the desert nomadic pastoral component of Nabatean society, constitute part of the larger and better-known Nabatean system of caravan routes and associated sites, in addition to village and urban centers dating between the late 4th century b.c.e. and the early 3rd century c.e. Campsites have rarely been explored in depth, although numerous small Nabatean camps and campsites have been registered in many surveys in the Negev. Four such sites in the Ruhot Plain, north of the Makhtesh Ramon, are detailed here. Architectural, geographic, and ceramic analyses show that these sites contrast with those associated with the classic Nabatean Incense Road, and for that matter, sedentary Nabatean society. The sites can be compared to nomadic systems associated with earlier Timnian, and later Byzantine and Early Islamic desert pastoral systems, as well as modern desert societies. Together, the materials offer a perspective on a little explored aspect of Nabatean society, the pastoral nomadic component, and an example of the archaeology of pastoral camps, often claimed to be inaccessible to archaeological study.

Pp. 23-43: “Olive Oil Production in the North-East Temple of Canaanite Lachish,” by Itamar Weissbein and Yosef Garfinkel

This article presents the results of the 2023 excavation at Tel Lachish, which re-examined Installation BB1132, uncovered in the central hall of a Late Bronze III structure dubbed the North-East Temple. As a result of the recent excavation, the installation was identified as an olive oil press. The article discusses the significance of olive oil production in Late Bronze Age Lachish and the possible role that its production played in the cultic activity conducted in the structure.

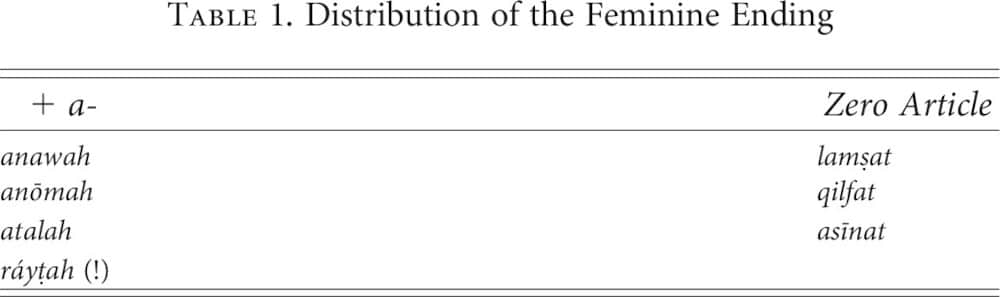

Pp. 45-55: “Qaṭrāyīṯ and the Linguistic History of Ancient East Arabia,” by Ahmad Al-Jallad

Qaṭrāyīṯ is a Syriac term that refers to the vernacular of east Arabia in the Early Islamic period. This linguistic variety is known from a small collection of lexical glosses in Syriac sources. Recently, Mario Kozah (2021, 2022) collected and examined about 40 Qaṭrāyīṯ lexical items, based on which he declared Qaṭrāyīṯ to be a dialect of Arabic. The purpose of this study is to re-assess the evidence, using a sounder linguistic methodology, to better determine the etymological origin of the Qaṭrāyīṯ vocabulary and, as much as possible, its phylogenetic position in Semitic. The results of this study increase the resolution of our image of east Arabia’s early linguistic history.

Pp. 57-78: “Reflections on the Circulation of Extraordinary Items in Early Chalcolithic Southwest Asia: Sourcing the Obsidian Mirror and Giant Blade Core of Kabri (Israel),” by Ron Shimelmitz, Tristan Carter, Branden Cesare Rizzuto, Rose Moir, Sariel Shalev, and Danny Rosenberg

The 6th-millennium B.C. obsidian mirror and giant blade core from Kabri, northern Israel, have long been considered epitomes of Southwest Asian Early Chalcolithic technical and artistic virtuosity. Nevertheless, even almost 70 years after their discovery, they are yet to be integrated into the growing body of research on obsidian circulation from Anatolian sources to prehistoric communities of the southern Levant. This paper presents for the first time the results of a provenience study employing handheld X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (hhXRF), showing that the obsidian used to fashion the mirror derives from East Göllü Dağ, central Anatolia, while the raw material used to make the giant blade core originates from the Bingöl B source in eastern Anatolia. Drawing on these results, it is suggested that the research of the obsidian trade and Early Chalcolithic social networks implicated in it can benefit from a more multifaceted distinction between sources, technologies, and end-products. Situating this work within the recent turn to more holistic characterization studies, alongside employing the theoretical lens of Joan Gero (1989), the authors argue that the mirror and blade core represent “extraordinary objects,” well-suited for the mediation of social relations in the context of emergent political and economic complexity.

Pp. 79-97: “The Vanished Fire Temple of Sarab-e Murt: A Tentative Interpretation of the Archaeological Evidence,” by Yousef Moradi

This paper presents the results of archaeological excavations at the southwestern site of Sarab-e Murt in western Iran. The investigations, conducted in 2008, revealed intriguing remnants of a significant sacred building, now obliterated due to the construction of a dam. All that remains of this structure are a few fragmentary walls, portions of a plastered floor, two clay installations, and five gypsum stepped stands. The architectural remnants are positioned in two distinct sections. In Section B, the structures are too limited in scope to allow for a comprehensive understanding of its original layout. Conversely, Section A, despite the fragmentary nature of the material, offers a more promising avenue for interpretation. By drawing parallels with well-preserved Sasanian Chahar-Taqs documented in other locations, a tentative reconstruction of this section as a Chahar-Taq with a bay on each side becomes conceivable. These archaeological findings suggest the existence of a Sasanian fire temple, distinguished by its unique architectural design. This temple served as a revered place of worship for the local Zoroastrian community in the Gilan-e Gharb Plain during the 4th–5th centuries C.E., and possibly even slightly earlier.

Pp. 99-153: “The Sacred Precinct of Tel Dan Revisited,” by Levana Tsfania-Zias

The sacred precinct or “High Place” of Tel Dan has been the subject of several studies since its excavation by Avraham Biran a half-century ago. The biblical account attributes its construction to Jeroboam I, at the northern border of his new Israelite kingdom. This account was taken at face value by Biran and by subsequent researchers. The stratified monumental features of the sacred precinct were attributed mainly to the 10th–8th centuries b.c.e. and its construction phases attributed to the more powerful, long-reigning Israelite kings mentioned in the biblical text—Jeroboam I, Ahab, and Jeroboam II. However, an analysis of the stratigraphy, architectural features, and the material culture of the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman periods reveals that much of what was assigned to the Iron Age should be reassigned to those later periods. Much of the material culture of the Tel Dan sacred precinct has parallels in Phoenician material culture.

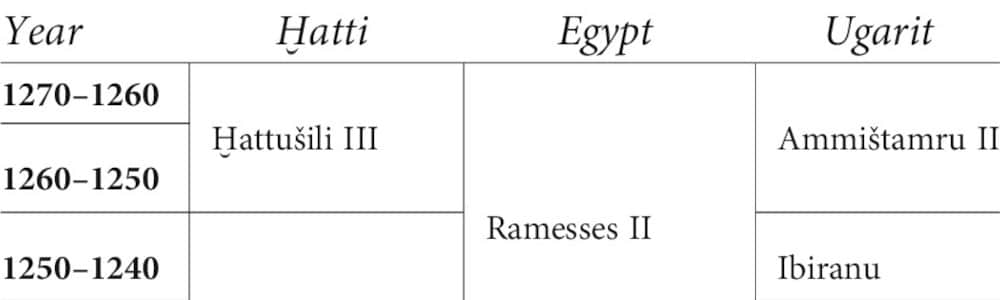

Pp. 155-168: “Remarks on the Ugarit Diplomatic Relations with Ḫatti and Egypt in the Late 13th Century B.C.,” by Eduardo Torrecilla

This paper addresses the seemingly contradictory foreign policy of Ugarit in the late 13th century B.C., since one can find Ugarit kings’ declarations of vassalage to Egypt while apparently being Hittite subordinates. It is stressed that in an empire-vassal relationship, a powerful subordinate is aware of having a strong hand, albeit not the upper one. The subordinate needs to defend their own interests, even when the counterparts know that the hierarchy is ultimately to be respected. Still, Ugarit no doubt remained loyal to Ḫatti, which welcomed the excellent relations between the courts of Ugarit and Egypt. Thus, the Hittite reprimands found in the House of Urtēnu archive do not necessarily tell of the sovereign’s weakness, but merely of two parties bargaining or “haggling” in search of a deal that better suits and protects each other’s interests.

ASOR Members with online access: log into ASOR’s Online Portal here. Once logged in, click the JOURNALS tab in the top navigation bar. Tutorials for how to log in to the Online Portal as well as how to navigate to the Portal Journals page can be found here.

Pp. 169-188: “An Intermediate Bronze Age Bead Assemblage from a Burial Cave at Givʿat Reḥelim (Tell es-Safa) in Northern Israel,” by Shlomit Bechar, Anastasia Shapiro, Yinon Shivtiel, and Uri Berger

Givʿat Reḥelim (Tell es-Safa) is located on the outskirts of Kibbutz Ayyelet HaShaḥar, in the southern part of the Hula Valley, in the northern part of modern-day Israel. About 50 caves were surveyed on the hill, including several intact burial caves dating to the Intermediate Bronze Age. A small excavation in one of the caves exposed a rich funerary assemblage, including dozens of beads made of carnelian, faience, red coral, and stone. Some of these materials are non-endemic to the southern Levant, and some of the beads were made using technologies that are foreign to the region; these facts indicate trade contacts with distant manufacturing centers. Determining their locations will shed more light on the complex international trade systems of the Intermediate Bronze Age (2500–2000 B.C.E.) in the Levant.

ASOR Members with online access: log into ASOR’s Online Portal here. Once logged in, click the JOURNALS tab in the top navigation bar. Tutorials for how to log in to the Online Portal as well as how to navigate to the Portal Journals page can be found here.