Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

November 2023

Vol. 11, No. 11

Moses in Josephus’ Antiquities: Between Jewish and Greek Traditions

By Ursula Westwood

In the Greek and Latin literature of the Roman Empire, Moses occasionally turns up as a wise but sacrilegious Egyptian priest (Strabo), a sneaky trickster who created a co-dependent community (Tacitus), or the founder of a “pernicious people” (Quintilian). While not everything said is wholly negative, it is true that when Flavius Josephus, Jewish rebel turned historian, wrote his Jewish Antiquities, he faced an uphill battle getting his non-Jewish audience to rethink their assumptions about who Moses was.

The Antiquities, which narrates the history of creation up to the Jewish Revolt, is Josephus’ second and longest work, written in Rome under the emperor Domitian (81-96 CE). His better-known Jewish War was written with some imperial support and for a broadly defined audience of “those under Roman power”, aiming to counter false narratives about the recent war, which was playing an outsize role in the self-definition of the Flavian dynasty. The Antiquities, written later and dedicated to a mysterious Epaphroditus, who may have been a wealthy freedman and book collector, presents itself in a more limited way, as of interest to “the Greeks”. This does not have to be understood exclusively, but certainly points to the fact that he is not writing for his fellow Jews, which is also suggested by his regular explanations of Jewish practices. He presents himself as writing for those who have either no knowledge, or incorrect knowledge, about ancient Jewish history; already in the introduction, he presents Moses as the foundational figure of that history.

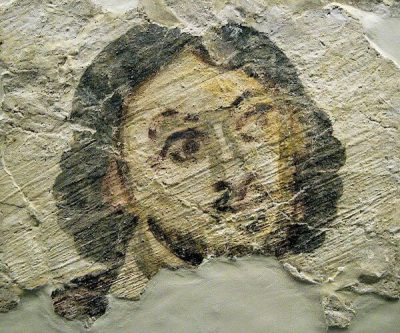

Inscribed wall painting depicting Moses, from a Coptic church in Egypt, 7th or 8th century CE. Benaki Museum, Athens, ΓΕ9073. Photo: Sharon Mollerus / Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0 DEED

Josephus takes on the challenge of countering his audience’s preconceptions about Moses in a variety of ways. Like the philosopher Philo, he has Moses live up to the ideals of Greek and Roman political philosophy, creating a virtuous people by means of laws in sync with the rationality governing the universe. But it is not only through linking Moses to philosophical ideals that Josephus appeals to a curious but potentially skeptical audience. It is also through the story of how Moses is born, raised, and forced into exile despite only ever showing loyalty to his adoptive Egyptian family. This is a narrative in which Josephus expands considerably on the brief account we find in Exodus by making use of extra-biblical traditions and weaving them together into a (mostly) satisfying tale involving recognition and role reversal, two literary staples of Greek tragedy. The story also has a solid theological message: God looks out for those who obey him.

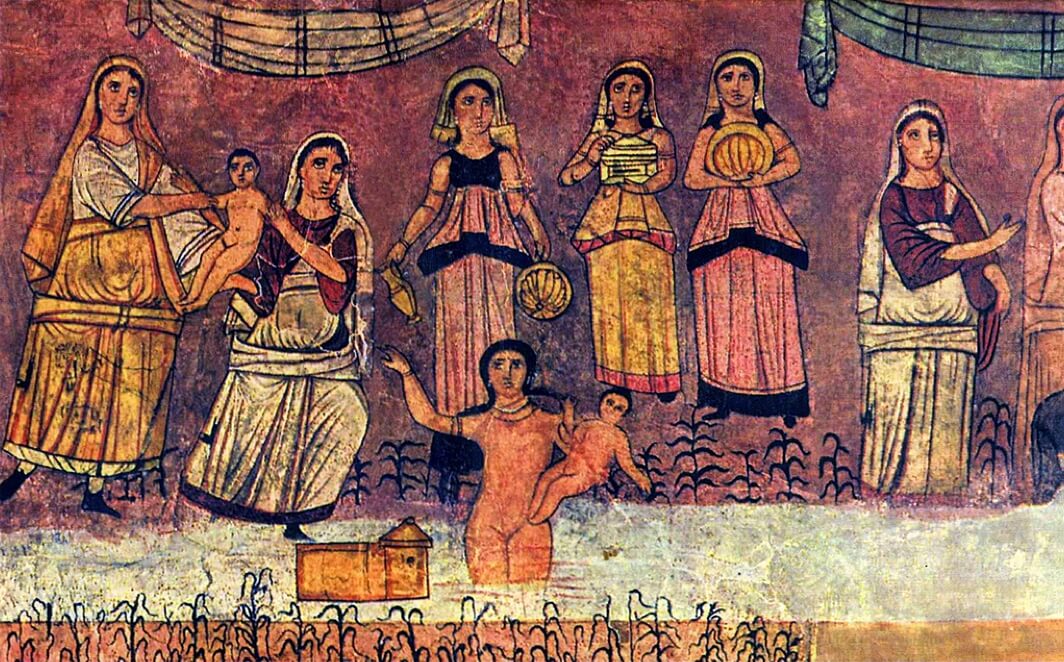

As in the biblical account, Josephus’ Moses is born under threat and placed — at the tender age of three months — in a basket in the Nile. He is found by the Egyptian princess Thermouthis, who instead of bathing (as in the biblical account), is playing with her handmaids by the river in a scene reminiscent of the Phaiakian Nausikaa’s meeting with Odysseus (Odyssey 6.100). Thermouthis is immediately struck with love for the infant, whose size and beauty are divine (Antiquities 2.224, 232).

Indeed, Moses’ remarkable qualities cause the childless princess to adopt him, presenting the toddler to her father the king as his successor. In a scene reminiscent of (but not precisely equivalent to) rabbinic stories of the infant Moses grabbing Pharoah’s crown (e.g Exodus Rabbah 1.26), Josephus’ Moses has the Egyptian crown laid upon his head, but then, in a moment of childish play, takes it off and stamps upon it. The affectionate scene in which Moses is embraced by the king swiftly changes as a sacred scribe leaps up and identifies Moses as the prophesied saviour of the Hebrew people and destroyer of Egypt (Antiquities 2.233-236).

Despite being identified as their nemesis, Moses nevertheless grows up in the Egyptian court, primed to be the next king. Aware of how contradictory this seems, Josephus observes that the king simply had nobody else who could do as good a job as Moses, particularly given the latter’s knowledge of the future, an attribute which Josephus seems to apply to him in light of the prophetic material found in connection with the Hebrew tribes towards the end of Moses’ life (Exodus 33).

An African sacred ibis, awaiting his marching orders. Photo: Jamain / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED

It is once he has grown into an adult that the next major moment of crisis comes — not through the murder of an overseer, as the reader familiar with the biblical story might expect, but through the Egyptians’ sudden need of Moses in the face of an Ethiopian invasion. Josephus prefaces this with a clear moral: Moses, he says, was given an opportunity to demonstrate that he had indeed been born to bring low the Egyptians and raise up the Hebrew people, as the sacred scribe said (Antiquities 2.238). The Ethiopians, who often appear as enemies of the Egyptians in ancient literature, invade Egypt, facing nearly no opposition. In dire straits and entirely lacking in the military nous required to deal with such an enemy, the Egyptian king consults oracles and is told that their only hope lies in Moses. Thus becoming general of the Egyptian army, Moses whips them into shape and, by means of strategic employment of ibises to cross a snake-infested desert, swiftly drives the Ethiopians back to their capital and besieges them.

It is at this point that a second princess appears in the story: much like Thermouthis, who was immediately taken by the infant Moses and saved him against the interests of her people, the Ethiopian princess Tharbis, trapped in the city and watching from the walls (like Helen on the walls of Troy, Iliad 3.161ff), catches sight of Moses leading the Egyptians and falls in love with him: like so many mythological princesses, she soon betrays her own people to help this foreign hero, letting him into the city in exchange for a promise of marriage. Unlike many of the Greek heroes (Theseus, for example), Moses honors this promise (Antiquities 2.253).

The tale of Moses’ time in Ethiopia is Josephus’ largest single addition to his biblical source. Scholars have speculated about where he found this story, often linking it with the reference to Moses’ “Kushite” wife in Numbers 12:1–10. Leaving aside problems with equating Ethiopia and Kush and accepting the possibility that the story does indeed have its origins in biblical exegesis, what is most interesting about it is how Josephus uses it to craft his version of Moses’ ethos in light of his audience.

In Aristotle’s famous analysis of tragedy (Poetics 16), he identified recognition and role reversal as two of the most powerful elements in the tragic plot. The story of Moses is not a tragedy. Yet in Josephus’ retelling, a moment of recognition, when the infant Moses is identified as the prophesied saviour of the Hebrew people, is immediately followed by a tale of role reversal, in which Moses becomes the saviour of the Egyptians instead — but his doing so leads to his own exile, as envy makes the king plot his murder.

If Josephus’ audience knew anything about Moses in Egypt, it was possibly that he was a renegade Egyptian priest. Josephus’ version of the story makes it clear that not only is there no question of Moses being Egyptian (even as an infant his Hebrew identity is revealed), but also that far from being a renegade, he was actually more loyal to — and supportive of — the Egyptians than they were of him.

The hostile references to Moses and Jewish practices in Tacitus, Juvenal, and Quintilian often accuse Jews of xenophobia and disloyalty, in a precursor to what will be one of the most pernicious forms of antisemitism. Josephus’ narrative about Moses appears to counter such claims by presenting the loyal general of Egypt in place of the renegade priest. At the same time, Josephus employs recognition, role reversal, and foreshadowing to craft a narrative which places the Jewish lawgiver in the Greek literary world. Moses in Josephus’ Antiquities is no hybrid (nobody ever thinks him Egyptian) but his story certainly is — blending Greek and Jewish cultural and literary traditions to create a compelling narrative to combat the anti-Jewish calumnies of Flavian Rome.

Ursula Westwood is Lecturer in Ancient Studies at Stellenbosch University. Her book, Moses Among the Greek Lawgivers: Reading Josephus’ Antiquities through Plutarch’s Lives, was recently published by Brill.

Want To Learn More?

The Myth of the Twelve Tribes of Israel

By Andrew Tobolowsky

The twelve tribes of Israel are, in a nutshell, how the Hebrew Bible’s historical narratives define Israel. Even today, the tribes are the ultimate through-line, the enduring symbol, what I have called elsewhere “the permanent, impermeable vision of who Israel is, and always will be.” The centrality of the twelve tribes tradition to the vision of Israel is indisputable. But did the twelve tribes actually exist? Well, it’s complicated. Read More

Are Possession and Other Spirit Phenomena Depicted in the Hebrew Bible?

By Reed Carlson

Many scholars rule out the presence of spirit phenomena in the Hebrew Bible. Reed Carlson explains why this is a mistake. Read More