Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

September 2023

Vol. 11, No. 9

Horvat Midras (Israel): A Window into Socio-Religious Change in Rural Roman Palestine

By Orit Peleg-Barkat and Gregg E. Gardner

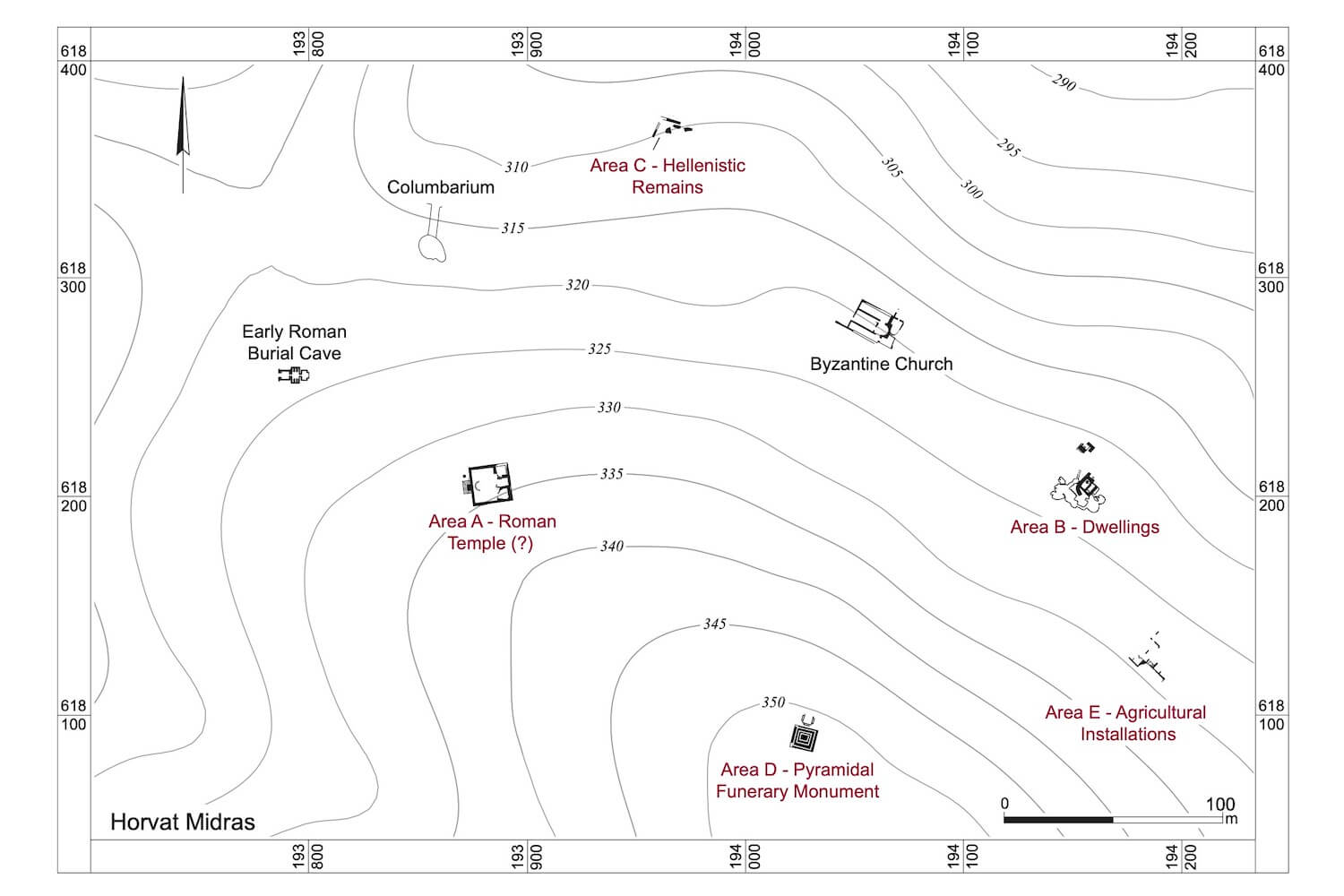

The ongoing excavation of Horvat Midras/Khirbet Durusiya (Israel) provides an opportunity to study changes in the ethnic and religious makeup of a rural settlement in the ancient southern Levant. While the vast majority of people in the ancient Levant lived and worked in agrarian settings, our knowledge of rural areas has been relatively limited, as historians and archaeologists have disproportionately focused on studying urban contexts. Horvat Midras was one of the largest rural settlements in the Judean foothills and was inhabited by several ethnic and religious groups from the fourth century BCE to the sixteenth century CE, including Idumeans in the Hellenistic period, Jews in the early Roman period, polytheists in the later Roman period, Christians in the Byzantine period, and Muslims under the Umayyads, Ayyubids, Mamluks, and Ottomans (Figures 1 and 2). As such, the site provides us with a window into social dynamics, interactions between and among ethnic-religious groups, and how rural life was impacted by military conflicts that prompted migration and abandonment, transforming the character of a rural village.

Our surveys and excavations to date suggest that the site was already inhabited in the late Persian or early Hellenistic period, apparently by Idumeans, as the material culture remains from this period strongly resemble those of the nearby city of Maresha, one of the major urban centers of Idumea. The Idumeans were a polytheistic group that included predominantly former Edomites who had migrated from southern Jordan but also incorporated former Judeans, Arabs, Nabateans, Greeks, and more. At Horvat Midras, the Idumean settlement seems to have ended with abandonment: pottery types, coins, and other finds found in the refuse heap on the northwestern outskirts of the site (Figures 3 and 4) end abruptly in the late second century BCE — corresponding to the time of the conquest of Idumea by the Hasmonean leader John Hyrcanus I. While Josephus (Antiquities 13.257–258) claims that the Hasmonean conquest of Idumea resulted in circumcision and conversion of the Idumeans to Judaism, the finds from Horvat Midras suggest something entirely different: namely, abandonment of the village, similar to the city of Maresha and other Idumean settlements in the Judean Foothills and the Arad-Be’er Sheva Valley. This shows that both cities and rural settlements in this region were subject to the same Hasmonean policy. It also challenges the previous scholarly hypothesis that cities were more Hellenized and therefore their inhabitants preferred to flee rather than to convert to Judaism, while village dwellers leaned towards the Jewish cause and joined the Hasmoneans voluntarily. This hypothesis, supposedly supported by certain affinities in material culture between the Idumeans and Judeans, seems to be invalid for the western and southern parts of Idumea.

Similar to other settlements in this region, there is no evidence that Horvat Midras was re-settled by the Hasmoneans, despite its strategic location on the road between Jerusalem and the coast by way of Maresha/Bet Guvrin and the site’s location overlooking the fertile Hachlil Valley.

Based on the archaeological evidence, the vacant site was resettled only in the late first century BCE, during the reign and perhaps under the direction of King Herod the Great (37–4 BCE). This new settlement was perhaps named Drusias, as some scholars have identified Horvat Midras with the Judean site mentioned by the second-century CE geographer Claudius Ptolemy (Geographiae V.16.6). It remains unclear whether the resettlement of the Judean Foothills under Herod was motivated by his Idumean ancestry, arose from the need to gift land to his supporters, or was simply the result of a natural process of expansion due to population increase at the time. During the early Roman period, several elaborately decorated family burial caves were cut into the bedrock to the east, south, and west of the settlement, signaling the affluence of some of the families that resided in the village or had rural estates here.

These shifts — the re-settling of the site and its socio-economic ascendence — are perhaps best emblematized by what remains the site’s most prominent feature: an ashlar-built pyramid on a podium (10 x 10 m) constructed at the top of the hill, the village’s highest point, marking an adjacent burial cave, presumably of a wealthy family (Figure 5). Whereas such pyramidal burial markers are well known from Jerusalem, where they could be viewed by the city’s numerous inhabitants or by the thousands of pilgrims flocking to the city three times a year, amplifying the family’s prestige, it is more unusual to find one in the countryside. Our visibility studies suggest that the pyramid burial marker (nefesh) could have been seen from all directions up to 6.25 kilometers away — including from the main road passing a couple of hundred meters to the west of the site. These indications that the village was relatively wealthy push back against the notion of rural areas as poor or backwaters.

The village was now predominantly Jewish, as evidenced by several ritual baths (mikvaot) and the use of chalk vessels, as well as the lack of figural art. That said, only one coin from the First Jewish Revolt against Rome (66–70 CE) has been found so far, raising questions as to whether the site was briefly abandoned or whether its residents took an active part in the rebellion.

Figure 8: Topographic map showing visibility of the Roman temple at Horvat Midras (GIS analysis: I. Wachtel)

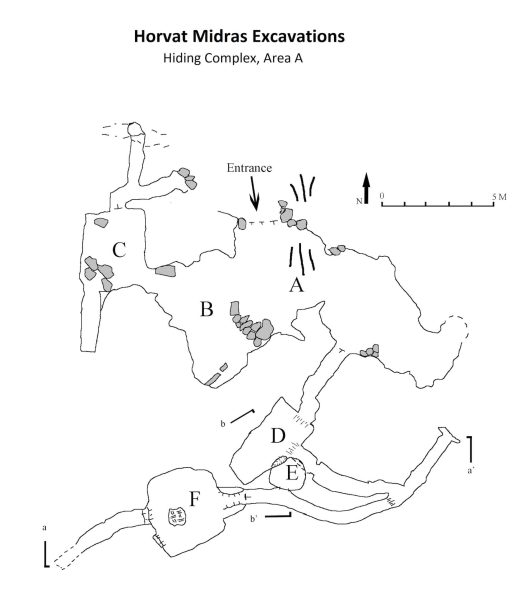

In any case, the village’s inhabitants certainly participated in the Second Revolt against Rome, the so-called Bar Kokhba Revolt (132–136 CE), as indicated by the construction of eight underground hiding complexes and several coins issued by the Judean rebel state headed by Simon Bar Kokhba (Figures 6 and 7). After the suppression of the Revolt, the village was again left uninhabited, as were other smaller Jewish villages in the vicinity. The religious and ethnic character of the site was again altered with the construction of what appears to be a temple or cultic complex on the western edge of the site, at a location overlooking the main road and seen from the road (Figure 8).

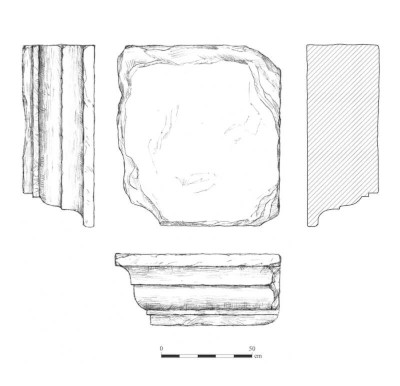

Previously identified by scholars as a synagogue, our excavations have instead suggested that this is one of the few temples known from rural Judea in the Roman period. The symmetrical ashlar-built complex (~20 X 20 m large) is nicely constructed and laid on bedrock (Figure 9). It comprises a raised, paved platform or podium accessed from the west via a wide staircase. On top of the podium, there is an open courtyard that drains into a large cistern north of the western staircase. At the eastern end of the courtyard, facing the western entrance, was probably a shrine of sorts. Unfortunately, only the supporting vaulted substructure survived, which was accessed via a staircase descending from the courtyard. The many architectural decorative pieces found in the collapse of the structure, including cornice pieces (Figure 10), a round niche, and an akroterion, support the notion that this complex included a small temple or a shrine.

Figure 10: A molded cornice found collapsed at the foot of the southeastern corner of the monumental building in Area A (Drawing: D. Porotski)

Built on a monumental scale — like the pyramid — this temple was meant to be seen from a significant distance, including from the main road. While Hadrian’s expulsion of Jews from the Jerusalem area in the wake of the Second Revolt compelled Jews to leave the city and its environs, the construction of a prominent and visible temple in an area that was previously densely inhabited by Jews who took an active part in the war against the Romans was likely intended to visually mark Roman victory, as well as the regained control of the region by the Roman army. The establishment of the temple, moreover, was likely part of an act by the Roman authorities to re-settle non-Jewish groups in areas of Judea formerly inhabited by Jews. Evidence for this resettlement can be seen in other nearby sites, such as Khirbet Burgin and Horvat ‘Ethri.

The site’s religious identity continued to shift. The local population gradually became Christianized beginning in the fourth century CE and a church with remarkably well-preserved mosaic floors was built at the site in the fifth century. After the Arab conquest of Palestine and the gradual conversion to Islam under the Umayyads, a mihrab (prayer niche) facing south was added to the church. After a decline of the settlement in the Abbasid and Crusader periods, the Roman-period temple was re-purposed in the Mamluk period (or perhaps earlier under the Ayyubids), using its ashlars to construct a watchtower on top of the southwestern corner of the podium overlooking the road. Under the Mamluks, the village seems to have reclaimed its status as a particularly productive and possibly wealthy agricultural site (Figure 11), as suggested by census and tax records at the start of the Ottoman period. Later under Ottoman control, the site again showed signs of decline and eventually would cease to be used as a sedentary settlement. The site’s numerous ancient artificial caves and underground installations (columbaria, storage facilities, hiding complexes, burial caves, etc.) were used as shelters for shepherds, who built sheep sheds at the entrances to the caves. The abandoned site was described as ruins by the 19th-century explorer Victor Guérin, though he noted that the ancient wells continued to bring life to local flocks.

What were the mechanisms that fostered the site’s changing identity? On the one hand, the site was abandoned several times, usually after a conquest or following a failed revolt. On the other hand, those who recognized the site’s fertility and agricultural potential seem to have been rewarded, as there are strong indications that when it was cultivated, Horvat Midras was particularly fertile and agriculturally productive. What initiated the village’s multiple re-settlements by successive ethnic-religious groups? What would repeatedly attract new inhabitants to an otherwise abandoned site? One wonders if, during a period of abandonment, the monumental structures that could be seen from afar sparked the curiosity of onlookers, causing them to wonder how such signs of wealth could exist in an otherwise non-descript location, perhaps beckoning them to take a closer look and leading them to discover the site’s rich potential. In any case, the site of Horvat Midras in many respects tells the story of the region and shows the importance of studying rural sites for understanding the history of ancient territories.

Orit Peleg-Barkat is Senior Lecturer in the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Gregg E. Gardner is Professor and Diamond Chair in Jewish Law and Ethics in the Department of Ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern Studies at the University of British Columbia. They are co-directors of the Horvat Midras Excavations. Their article, “Conspicuous Construction: New Light on Funerary Monuments in Rural Early Roman Judea from Horvat Midras,” will be published in the journal BASOR later this year (Volume 391).

Acknowledgments:

We thank the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the University of British Columbia for their continued support of this project, and to the undergraduate and graduate students from these two universities who participated in the excavation, including some as expedition staff. We would also like to thank the dozens of volunteers from Israel and abroad who have joined the excavation seasons.

The project was funded by the Israel Science Foundation, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Roger and Susan Hertog Center for the Archaeological Study of Jerusalem and Judah, the International Catacomb Society, the Halbert Center for Canadian Studies at the Hebrew University, the Albright Institute for Archaeological Research, and the Israel Nature and Parks Authority.

Want To Learn More?

They Were Not Mainly “Peasants” Towards an Alternative View of Village Life in Greco-Roman Palestine and Egypt

By Sharon Lea Mattila

It has been very common for the vast majority of the people in the Greco-Roman world, with the exception of those who lived in the élite urban spheres, to be depicted as a homogeneous mass of “peasants”—members of subsistence-oriented, self-provisioning “peasant family farms,” living in tradition-bound, autarchic village communities, at slightly above subsistence after rents and taxes were paid. Market exchange, according to this received wisdom, was at best peripheral and indeed inimical to this “peasant” mode of existence. Instead, barter was supposedly the predominant and preferred means by which “peasants” exchanged their produce for the few necessities that they themselves could not produce. Read More

Shikhin Between Jews and Romans

Shikhin Between Jews and Romans

By James Riley Strange

Most archaeological sites in the ancient world are important for one reason or another. But every once in awhile, archaeologists uncover one that that helps them solve long-standing problems, or that opens up a new tin of questions that must be answered. Read more