Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

August 2023

Vol. 11, No. 8

Who Really Invented the Alphabet?

By Seth Sanders

Who really invented the alphabet? Despite its vast influence, we are still uncertain about precisely where the world’s most influential communication system came from. One reason for this uncertainty is that debate about the alphabet’s origins has tended to focus on questions for which there is little clear evidence, such as the exact date of its invention and the personal identity, social status, and educational background of the inventor(s).

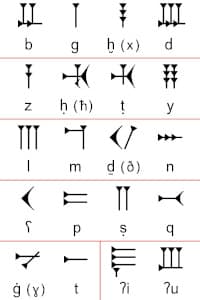

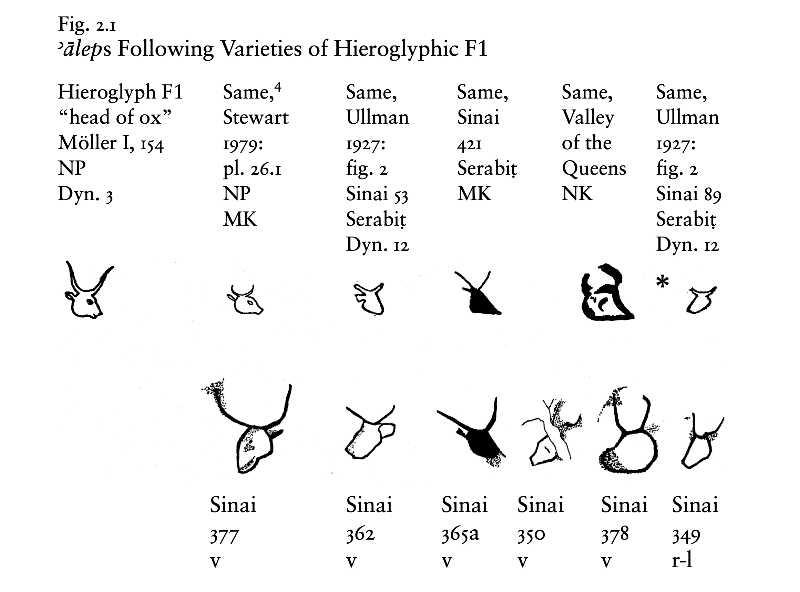

What we know for sure about the early alphabet’s background is linguistic and material. It is widely agreed that the early alphabet a) represents a West Semitic language ancestral to Hebrew, Arabic, and Aramaic; b) but based its signs on the Egyptian writing system, and c) was— as far as we know— not done by scribes or professional writers but written exclusively as graffiti and informal carvings. Each sign got its name and phonetic value by the acrophonic principle, using the first sound of a word. A bull’s head became the basis for the alef sign (our A) because the early West Semitic word for bull ˀalpu begins with an alef sound. A house is the basis for the bêt (our B) sign because the early West Semitic word for house was baytu.

But because all of our early alphabetic texts are instances of reuse—we have no “smoking gun” for its invention— there is no direct evidence about the social class or education of whoever developed this alphabet, nor about whether it was created by an individual at a single moment or a group over time. Yet the most heated arguments have been over precisely this. Anson Rainey thought the alphabet was invented by a “genius” educated in Egyptian writing at a bureaucratic center, while Orly Goldwasser takes as a “working hypothesis” that the inventors were a group of nonliterate Canaanites working in the desert. Without assuming a lone genius, Christopher Rollston accepts Rainey’s assertions about the inventors’ social class and education based on abroad general assumption about the nature of writing in the ancient world: “[u]ltimately, writing in antiquity was an elite venture”.

But later and clearer evidence on the uses of writing in the ancient Mediterranean shows that the alphabet was not the sole property of educated elites or bureaucrats. For example, we have hundreds of texts from the first 200 years of Greek alphabetic writing (about 750-550 BCE), but they refer mainly to festive contexts of drinking, dancing, and sex, as well as dedications to gods. There is no evidence for early political, scholarly, or bureaucratic use. Similarly, many of the main teachers and writers of early Latin were slaves. If early Greek writing was for partying and personal offerings, and Latin often the province of the lowest-status individuals, then we cannot assume that ancient Mediterranean alphabetic writing was owned by highly educated writers or uniformly the province of elites.

So, we cannot answer definitively about the social class or educational level of the inventor(s) of the alphabet. However, we can (and should) ask if the early alphabetic inscriptions show any signs of scribal training—whether in Egyptian writing or in the alphabet itself. Because in fact there is ample evidence about what linguistic knowledge the earliest alphabetic writers did and did not draw on.

There are two parts to this. First is whether the early alphabet shows any evidence that its creators knew how Egyptian writing worked. Egyptian has two main ways to write: ideographic, where each sign stands for an idea, category, or word rather than any specific sound, and syllabic, where each sign stands for a specific syllable. Most Egyptian signs had multiple readings, often both ideographic and syllabic. For example, the“ house” sign that is the source of the Hebrew bêt (and therefore Greek beta and Latin/English B) originally never had anything to do with a “B” sound in Egyptian. Instead this sign was used ideographically to represent the category of houses and added to any word for a dwelling. But the house sign could also be pronounced syllabically as the Egyptian word for “house”, per, as in the word for ruler, Pharaoh, literally “great house.” There was also a specialized set of alphabet-like signs that stand for single consonants rather than a syllable; these were used to write foreign words and names, among other functions. Using this system Egyptians were already able to write West Semitic words consonant by consonant, and we know they did this because we have many West Semitic names, as well as a West Semitic magic spell against serpents transliterated onto one of the walls of the Old Kingdom Pyramid of Unas. So the question is, do the creators of the alphabet show any knowledge of this?

Second is whether the early alphabet was systematized and taught carefully, or casually and chaotically transmitted—a script of scribes or of the people. Some time ago, in line with Goldwasser’s arguments, I argued (first in a 2004 article, then a few years later in my book, The Invention of Hebrew) that the alphabet showed no sign of scribal transmission in its first 500 years. It was, as Goldwasser says, a “script of the poor,” until it was adopted by scribes and rulers in a special new way—as a symbol of local culture and belonging. Does this hold up?

First, is there any connection between the Egyptian and West Semitic sound values of the early alphabet’s sign inventory? No. The alphabet was derived from the Egyptian sign inventory on a strictly visual basis, with no reference to the Egyptian sound values. This is clear from a comparison between the sound values of each of the 26 probable original alphabetic signs and their Egyptian sources. In no case do they attempt to represent the same sound.

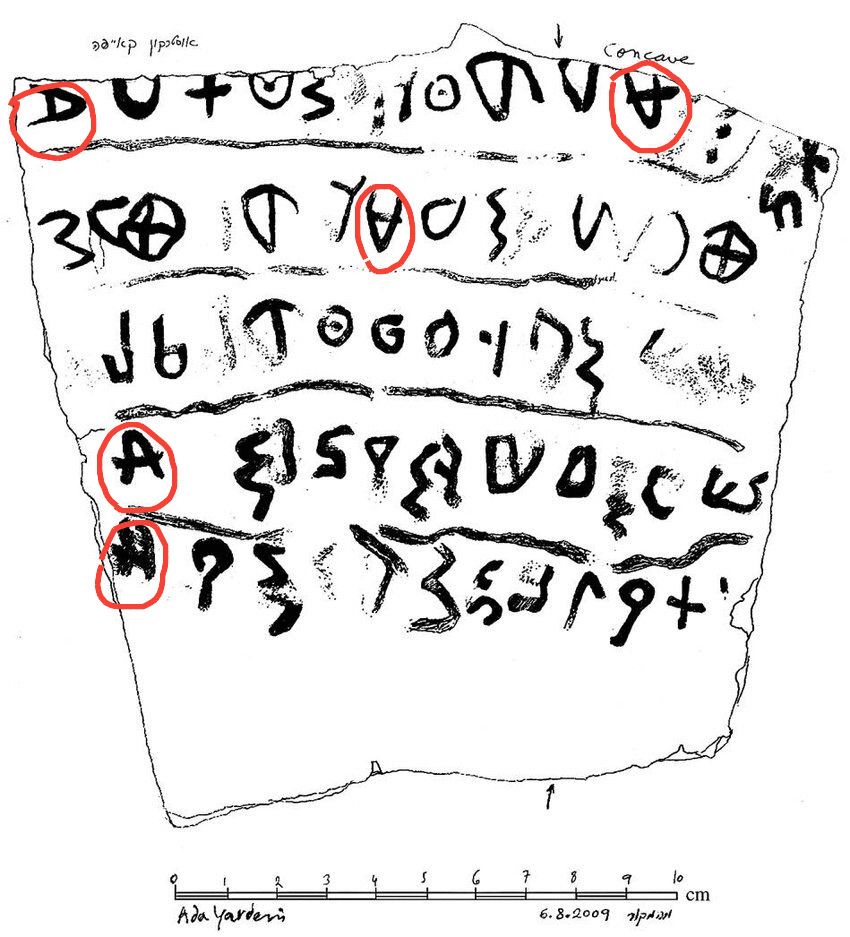

But I found something more. The evidence of a strictly visual and not linguistic basis goes further than this, because in multiple cases the alphabet’s creators combined visually similar but linguistically different Egyptian signs that had the same name in West Semitic but completely different senses and sounds in Egyptian. For the 26 West Semitic sounds the early alphabet seems to represent, we actually find no less than 32 different signs, because in six cases the inventors picked multiple Egyptian signs without regard to their Egyptian meaning or phonetic value.

Two examples will illustrate what I mean. First is the “house” sign mentioned above. It is clear that rather than picking one sign to consistently stand for one sound, the alphabet’s inventors grabbed anything from the Egyptian inscriptions they saw that looked to them like a house, without regard for its actual reading in Egyptian. So for the B sound they used the “house” sign (O1/O1B in Gardiner’s hieroglyphic sign list) but also a totally linguistically unrelated sign, “reed shelter” (O4/O4B) since they look more or less the same if 1) you can’t read Egyptian or 2) you just don’t care. An even more chaotic pattern appears in the origins of the sign for the D sound. Here they couldn’t make up their minds and different inventors seemed to just grab two different signs for things that started with a D sound in West Semitic, even though neither was remotely related to Egyptian pronunciation of that sound. First is the Egyptian“door” sign (O31), used to write West Semitic daltu (Hebrew delet). But second, they also picked “fish” (K1), used to write West Semitic dagu (Hebrew dāg). Not only did they ignore the Egyptian sound value of each original sign, they treated them purely visually and from a purely West Semitic standpoint.

A second way in which the alphabet’s inventors either deliberately ignored or were simply unaware of Egyptian scribal techniques is their avoidance of the Egyptian single-consonant system. For there was already a set of 25 monoconsonantal forms in Egyptian. Anyone trained in Egyptian writing who had contact with West Semitic names or words would have been able to write these in the Egyptian alphabetic subsystem. Yet there is no sign the alphabet’s inventors tried to do that.

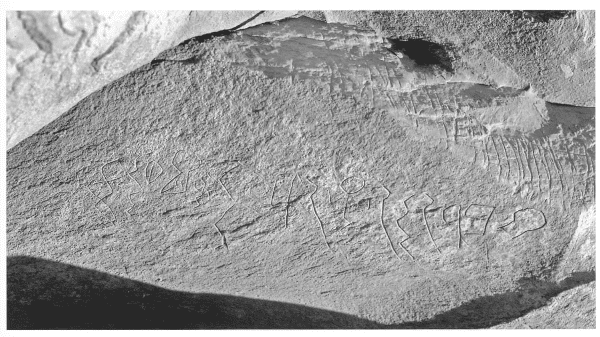

We can combine these observations with other evidence suggesting the early alphabet was taught casually, not systematically. The first alphabetic inscriptions show great irregularities in their direction and stance (e.g. boustrophedon, spiral) that are rarely encountered in scribal Egyptian. And second, they display a single-file orientation (as opposed to writing in groups), which is extremely rare in scribal writing of Egyptian but dominant in alphabetic writing. Both features of early alphabetic writing cannot be explained by professional scribal transmission but make perfect sense as a result of informal transmission, on the margins of official culture.

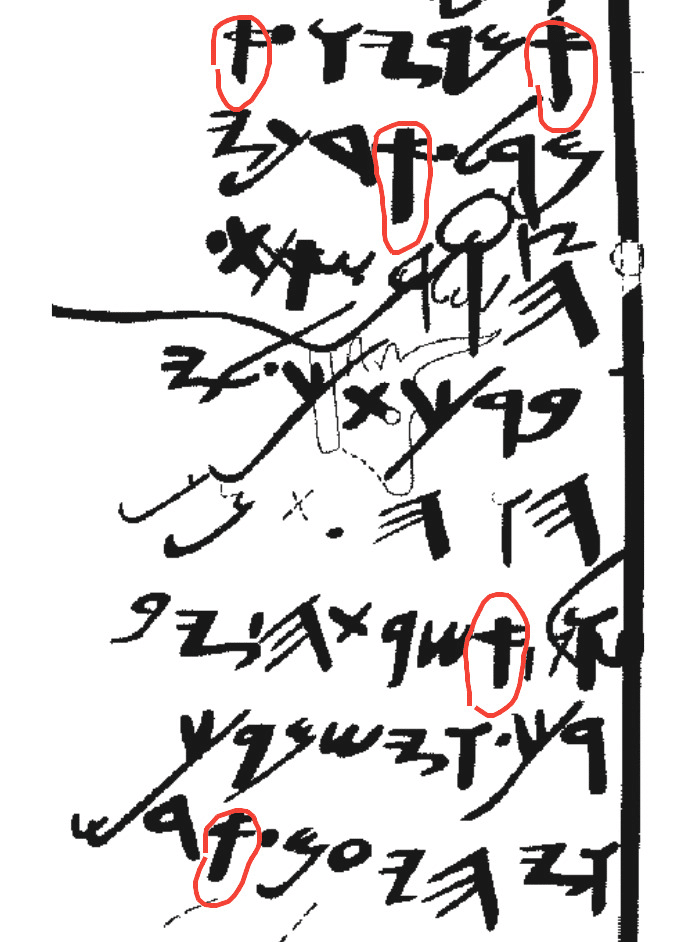

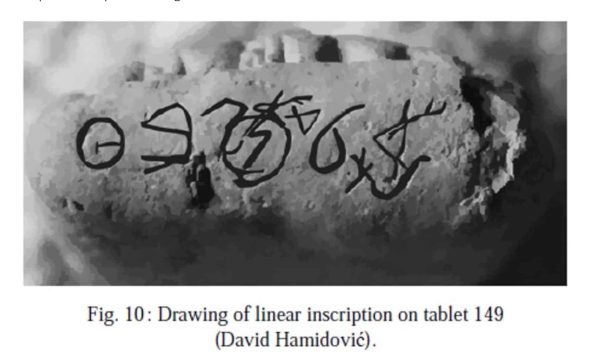

Remarkably, two recent discoveries from around 1500 BCE do show scribes using the alphabet. But these exceptions prove the rule, because these scribes used alphabetic writing just as sloppily or playfully as its other users did. In an obscure Egyptian ostrakon from Thebes and a handful of looted cuneiform tablets we find surprising confirmation that even professional writers used it unprofessionally.

This creation of new kinds of writing outside the bureaucratic center has a striking parallel with the Greek alphabet. Sometime during the mid-Iron Age, seafaring merchants who came into contact with the Phoenician script reconfigured it to represent Greek. Again, it was precisely their lack of loyalty to the strictly consonantal principles of Phoenician writing—through either misunderstanding or independence or both— which allowed them to reuse certain Phoenician consonantal signs with no corresponding sound value in Greek as vowels. In fact the contact was actually closer because the majority of Phoenician sign values were retained in Greek. The Sinaitic context in which the alphabet was probably invented looks strikingly like the Mediterranean context in which it was reinvented.

In conclusion, whether the alphabet was invented and reproduced by learned scribes who chose to systematically disregard everything they knew about both Egyptian and scribalism, or whether (more plausibly) it was creative people at the margins, it is clear that a theory of the alphabet as a casual and playful mode of knowledge explained all of our evidence when I first tackled this back in 2004, and still (encouragingly) explains all of the new evidence discovered in the 20 years since. What we lack is a theory of play as a mode of creativity and knowledge production in ancient writing, which I suggest as a new frontier for research on the early history of writing.

Seth Sanders is a Professor of Religious Studies at the University of California, Davis, and the author of The Invention of Hebrew (University of Illinois Press, 2009).

Want to learn more? Professor Sanders will be giving a webinar for the Friends of ASOR on this topic on August 31. Register Here!

Want To Learn More?

The Lost Link

By Brian E. Colless

I have just made a surprising discovery about the way the alphabet was used by the Israelites in their early period of settlement in the Promised Land, that is, the time of the Judges (including Samuel) or, archaeologically speaking, Iron Age I (ca. 1200 to 1000 BCE). Read More

The Alphabet: The First Thousand Years

By Aaron Koller

The alphabet is probably the most important information technology ever invented. But why did it take a millennium to spread unevenly around the ancient Near East? Read More.

The Social Context of Writing in Ancient Ugarit

The Social Context of Writing in Ancient Ugarit

By Philip Boyes

Writing creates physical objects using communications systems. But it is also a social act. What does the multiplicity of languages at the Late Bronze Age site of Ugarit tell us about people and identities? Read More