Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

August 2023

Vol. 11, No. 8

Before and After Babel

By Marc Van De Mieroop

“But the LORD came down to see the city and the tower the people were building. The LORD said, “If as one people speaking the same language they have begun to do this, then nothing they plan to do will be impossible for them. Come, let us go down and confuse their language so they will not understand each other.” Genesis 11:5-7

Anyone familiar with the ancient Near East knows this passage from the biblical book of Genesis, an aetiology explaining why people on earth came to speak many languages after they had used only one. No linguist today would accept the explanation as true, and this note will certainly not argue the opposite. There was a fascinating parallel in the ancient history of the Near East, however, not in what languages people spoke but in what they wrote. In the third and second millennia BCE, until the collapse of the Bronze Age, every intellectual there used the same system of writing, that is, cuneiform script to render the Babylonian language. Yet, after the Dark Age at the turn of the first millennium, a large variety of languages with their own scripts emerged. A Babylonian cosmopolis turned into an Eastern Mediterranean vernacular world. What happened and why?

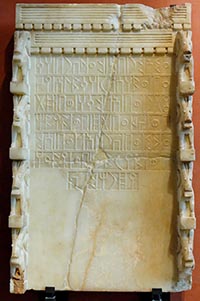

A letter written in the Babylonian language and cuneiform script found in Tell el-Amarna, Egypt. King Abi-milku of Tyre (modern Lebanon) sent this letter (EA 153) to the king of Egypt to announce that Tyre’s ships were at his disposal. Metropolitan Museum of Art 24.2.12.

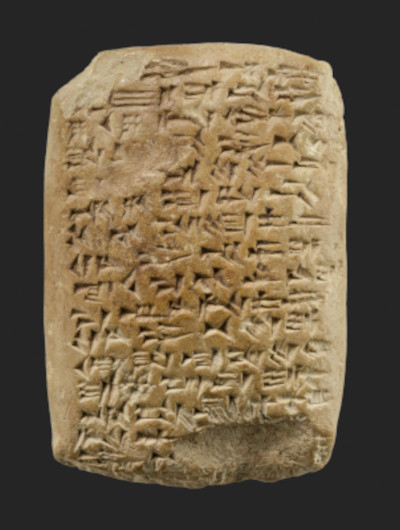

Let us look first at the cosmopolitan age, the period from the mid-third millennium to around 1200 BCE. At the start, the cuneiform script, which was invented in southern Babylonia most likely to render the Sumerian language, had become used to record Babylonian Akkadian as well and had been adopted by people as distant as Ebla near the Syrian coast.The latter did so not in consequence of Babylonian military expansion, but before that happened. Slightly more than a millennium later, in the so-called Late Bronze Age (often labeled the first international age in world history), we find that even in the court of Egypt, a country with its own age-old scripts and written language, there were scribes who could write Akkadian in cuneiform on clay tablets. Their colleagues in Anatolia, Western Iran, and the Syro-Palestinian area all did the same and shared a high literary and scholarly culture with intellectuals in Babylonia and nearby Assyria, when the former was a weak player on the international scene and before the latter flexed its military muscle.

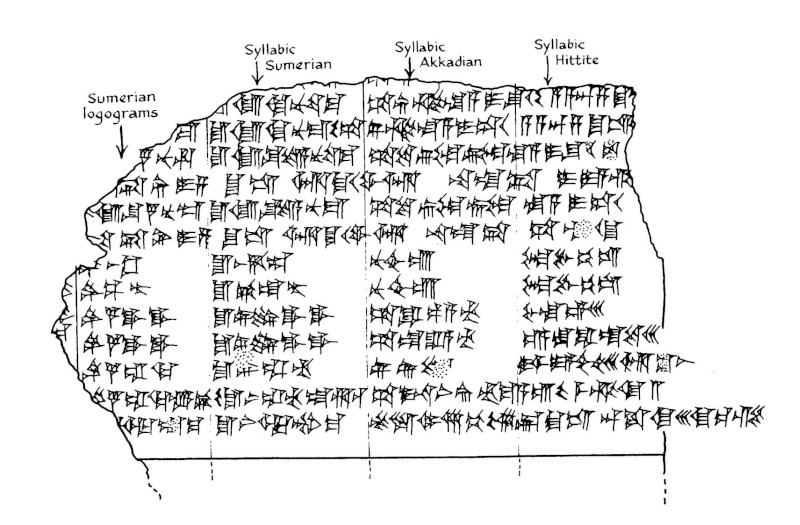

Today one often sees the writers outside the Mesopotamian heartland presented as “peripheral” and indeed their work shows local variants. But rather than seeing these writers as inferior students making mistakes, we should appreciate them as knowledgeable and creative, rendering the materials more relevant to them. They took the high points of Babylonian literature and scholarship and modified them through expansion, rephrasing, paraphrasing, and other means. The Epic of Gilgamesh, for example, appears at Hattusas in Central Anatolia in versions that move the focus of attention to the western adventures, much nearer to Anatolia than distant Uruk, and scholars there added Hittite versions to Babylonian lexicallists. Scribes wrote local languages in the Babylonian cuneiform script as well—Hittite, Hurrian, Elamite, Amorite—or even in an especially invented one (Ugaritic), but those were for local affairs or to quote ritual spells in the vernaculars. Any work of high culture was done in the cuneiform system as it was first used in Babylonia, with a mixture of the Sumerian and Akkadian languages either on their own or in parallel in bilingual texts. If you wanted to be called an intellectual at that time anywhere in the Near East, you had to be able to express yourself in these ways.

Fragment of a shell inscribed with Luwian hieroglyphs, one of a small group excavated in the Assyrian capital city Kalhu and inscribed with the name and title of a 9th-century king of Hamath in western Syria, Irhulina. Metropolitan Museum of Art 64.37.15

Now let us look at the next millennium. In political terms, the Near East had changed from a multipolar world to one in which vast, Mesopotamia-centered empires dominated: Assyria, Babylonia, and Persia in succession. One could imagine that the cuneiform writing practices so rigorously preserved in the imperial core continued in use in the newly conquered regions, most of them in the west (after all, the spread of the Latin language and its alphabet was on the back of Roman imperial expansion). While indeed in some footholds of imperial administration cuneiform was in use, throughout the region in direct contact with the empires and beyond it a multitude of scripts recording various languages appeared in common use. Most of them–Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, and others–were written in their own alphabetic script (each a modified version of the Phoenician alphabet), but not all. In northern Syria and southern Anatolia the Luwian language was written in its own hieroglyphic script, which had the same variety and large number of signs as cuneiform and by all appearances was more cumbersome to write out. That case by itself shows that the popularity of vernaculars and alphabets was not because they were easier. Nor were they more democratic; their use was the outcome of choices made by local courtly elites, not by the people.

Those decisions were conscious and deliberate, involving not only languages and scripts but also writing supplies. The unfortunate consequence for historians today was that the latter included much parchment and papyrus instead of clay, materials that much more easily vanished over time. Luckily, much literary creativity survived as it became part of traditions of copying and elaboration throughout later centuries. Best known, of course, are the biblical and Greek texts, but there are also Aramaic ones such as the Story of Ahiqar. These works were created in the shadow of empires, often when the threat of the latter was looming or after the authors’ people had lost independence and become imperial subjects—the Judeans in exile, for example. These authors did not just imitate models from the imperial core where the cuneiform tradition was preserved and developed, but oftentimes creatively modified these models to contest and undermine their messages. These were acts of resistance. The Tower of Babel story quoted above contains a mock Babylonian building inscription and turns the idea that Nebuchadnezzar’s rebuilding of Babylon was a creation of order into one of disorder and confusion. Likewise, in fifth-century Athens the playwright Aeschylus in The Persians turned the Mesopotamian trope of Ionians as fish escaping into the sea around by presenting the Greeks at Salamis killing off Persians like fish in the sea.

What caused this shift from widespread use of cuneiform to a preference for locally developed scripts is, of course, hard to determine—no ancient author tells us. But what we can say is that both in the cosmopolitan age as in the vernacular one high literature was Near Eastern, not simply Babylonian. The writers whom we place in the periphery were well-versed in “Babylonian” culture. At first they acquired it in order to participate in its development, enriching it through elaboration and modification. They did so voluntarily; there was no political force behind it. Later on, however, when military actions from the Mesopotamian empires absorbed their countries, they continued to know what went on in cultural terms but now used this knowledge to contest this power. They kept their intellectual independence, proudly proclaiming their individuality, even if they were no longer free.

Marc Van De Mieroop is Miriam Champion Professor of History at Columbia University. His latest book, Before and After Babel: Writing as Resistance in Ancient Near Eastern Empires, recently appeared at Oxford University Press.

Want To Learn More?

Sumer and the Modern Paradigm

By Pedro Azara

Joan Miró used Son Boter, a 17th century mansion at Palma de Mallorca (Balearic Islands, Spain) as his studio for sculptures. On its walls were images of what most most scholars believed were ethnographic or traditional art. But in reality these were Sumerian masterpieces from the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad. Read More

The Alphabet: The First Thousand Years

By Aaron Koller

The alphabet is probably the most important information technology ever invented. But why did it take a millennium to spread unevenly around the ancient Near East? Read More

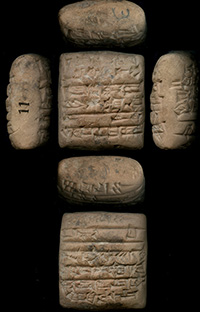

How to Spot Fake Cuneiform Tablets

How to Spot Fake Cuneiform Tablets

By Sara Brumfield

A surprising number of cuneiform tablets are fakes; museums are full of them. How can a visitor begin to spot them? Read More