Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

July 2023

Vol. 11, No. 7

Heartbreak and the History of Distress in Ancient Mesopotamia

By Moudhy Al-Rashid

The concept of “heartbreak” appears multiple times in cuneiform texts as a metaphor to describe both mental and physical conditions. How should we interpret this phrasing? And is it anything like heartbreak today?

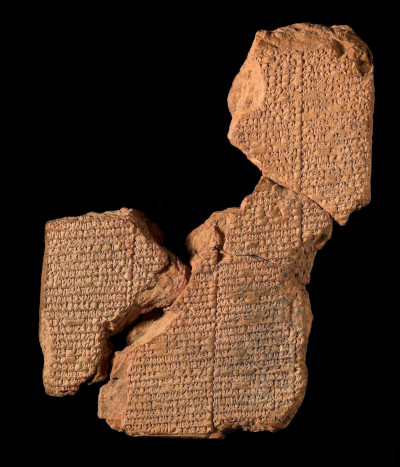

Figure 1: Tablet III of the Epic of Atrahasis (the Great Flood). Old Babylonian (ca. 2000–1600 BCE). BM80385. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

Sometime in the last half of the 17th century BCE in Babylonia, a scribe named Ku-Aya impressed onto three tablets a creation epic in cuneiform that told of a great flood (Figure 1). In the story, the gods created people to bear their toil. But when the din of humans toiling away grew so loud that it disrupted their divine sleep, the gods sent a deluge to wipe out their creations. Enki (also known as Ea), the mischievous god of wisdom, found a way to warn a man named Atrahasis of the plot and instructed him to build a boat to preserve what life he could.

Atrahasis enlisted the help of his fellow citizens in its hasty construction before inviting them to a banquet on the eve of their deaths. As they sat down to what they did not know would be their last supper, reality hit Atrahasis.

“But he was in and out: he could not sit, could not crouch,

For his heart was broken and he was vomiting gall.” (Tablet III col. ii, lines 45-47).

The expression used here—“his heart was broken”—is a somewhat literal translation of the verb ḫepû “to break” and noun libbu, a word with a wide semantic range that among other things can refer to the “heart” as an organ of thought and emotion that figures in numerous expressions of emotional distress.(The heart, for example, can be “low” to express what may be a depressed state.)

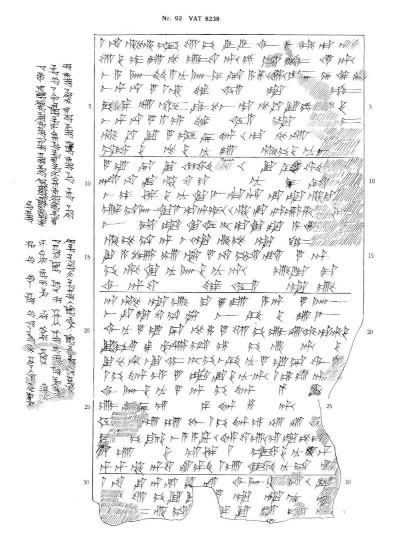

The pairing of “heart” and “break” occurs not just in famous works of Babylonian literature, but also in highly technical medical texts, among numerous other terms that capture mental distress alongside other forms of suffering. A medical therapeutic text (Figure 2) from the 7th century BCE library of Kiṣir-Aššur groups the expression with fear, grief, and foolish thoughts, all of which are blamed on divine anger:

“If a man, his heart continually breaks, (and) on repeated occasions, he is afraid, that man, anger of god and goddess is over him.” (BAM 316 iii 8′-9′.)

Following a medical prescription, the text then pairs a variation of this, ḫīp libbi “heartbreak”, with feeling fear day and night (iii 13’), and with grief and foolish thoughts (iii 23’-24’). Elsewhere in the tablet, the symptom appears with nightmares and a host of social misfortunes that would easily bring on emotional distress of any kind (ii 5’-9’; CMaWR II, Text 3.6).

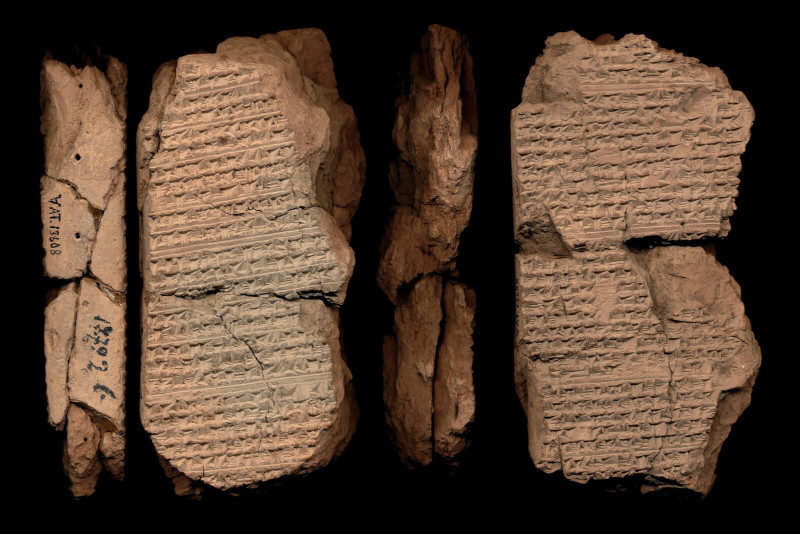

Figure 3: Anti-Witchcraft Text, Neo-Assyrian Period (ca. 911–612 BCE). Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. (Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative P369073).

In anti-witchcraft texts (Figure 3), the expression also appears in diagnostic descriptions alongside terms that denote emotional distress. “If a man continually has heartbreak, and his heart ponders foolishness”, reads another brief description of symptoms blamed on witchcraft, known from various Neo-Assyrian copies found at Nineveh and Assur. The treatment includes a ritual involving figurines and an incantation to Shamash that reverse some of these symptoms.

“Foolishness, heartbreak, fear, (and) fright which I constantly experience and suffer in my body, in my flesh, and in my sinews.” (CMaWR I, Text 7.7, lines 21-22)

These lines are particularly illuminating, as they group heartbreak with cognitive and emotional distress, all of which are experienced physically– in the body, flesh and sinews. Other diagnostic introductions to anti-witchcraft texts find the expression grouped with similar types of experiences, including foolish thoughts, forgetfulness, depression, fear, sweats, sleeplessness, and irritability, among others (e.g., CMaWR I, 2.3, 8.6, 8.7). Physiological symptoms, like pain and loss of libido, are also described as accompanying heartbreak in some texts.

The same medical professionals who presumably copied and employed such texts that reference the broken heart expression used variations of it in their correspondence. When the exorcist (āšipu) Urad-Gula was banished from the royal court in the 7th century BCE, his father wrote to the king to petition on his behalf: “He is dying of a broken heart (ḫūp libbāte)”, he writes of Urad-Gula. Another medical professional named Nabû-tabni-uṣur complains of neglect in a letter to king Esarhaddon (Figure 4). He ends the missive by proclaiming that he is “dying of a broken heart (kusup libbi) and that “heartbreak” (ḫīp libbi) has seized him.

Figure 4: Letter from Nabû-tabni-uṣur to Esarhaddon (reigned ca. 681 – 669 BCE) (Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative P334358).

A number of translations have been offered to try to make sense of the cuneiform “broken heart”. J. Scurlock, whose prolific work on medical texts has made hundreds of them available for study, translates it as a “crushing sensation in the chest” associated with a cardiac event. An early analysis of pathological terms by P. Adamson interprets it as abdominal pain that accompanies cardiac angina. E. Ritter and J.V. Kinnier Wilson favor “nervous breakdown”, and in their recent publication of anti-witchcraft texts, T. Abusch and D. Schwemer use “depression”. M. Stol opts for the translation that is both the most literal and figurative, “heartbreak”, which I have retained for these reasons.

Heartbreak is, perhaps, all of these things (or none) in different contexts. Based on its usage in the handful of texts cited here, it represents something like anxiety. In the letters, it seems to follow from experiences of stress, like insufficient pay or outright royal rejection. In the therapeutic texts, it often appears alongside other symptoms that evoke cognitive disruption or emotional distress, like depressed states, forgetfulness, and fear, and confirms that these experiences were taken seriously enough to warrant medical attention.

The written history of mental symptoms and illness is a long one that begins in some of the earliest known written records. The way cuneiform scribes and scholars rendered these experiences intelligible relied on their social and intellectual context, and the great age of these texts reveals that we have suffered experiences of mental distress for millennia, even if we have understood, organized, and labeled such distress in different ways. “Heartbreak” and its concomitant symptoms are just one example of how scribes and scholars articulated these experiences in ancient Mesopotamia.

Although we may never know exactly how to translate this pairing of libbu and ḫepû, we know that it was an experience that could follow from stress, be it work stress, social stress, or the extreme stress that would accompany the eve of humanity’s destruction. It could appear with fear, sorrow, foolishness, forgetfulness, sleeplessness, strife, and other symptoms that illuminate something about mental suffering in ancient Mesopotamia. To many today, it may resonate as a familiar experience– a reminder of what we share with the people who came before us, and of the very ancient and ongoing attempt to make difficult experiences make sense.

Moudhy Al-Rashid is an Assyriologist and postdoctoral scholar at the University of Oxford. Her article “‘His heart is low’: Metaphor and making sense of illness in cuneiform medical texts” recently appeared in the journal Avar.

Further Reading:

CMaWR I = Abusch, T. and Schwemer, D. 2011. Corpus of Mesopotamian Anti-witchcraft Rituals: Volume One. Leiden: Brill.

CMaWR II = Abusch, T. and Schwemer, D. 2016. Corpus of Mesopotamian Anti-witchcraft Rituals: Volume Two. Leiden: Brill.

Adamson, P. 1981. Anatomical and Pathological Terms in Akkadian: Part III. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 113(2): 125–32.

Lambert, W. G., and A. R. Millard. 1969. Atra-Hasīs: The Babylonian Story of the Flood. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Ritter, E. K., and J. V. Kinnier Wilson. 1980. Prescription for an Anxiety State: A Study of BAM 234. Anatolian Studies 30:23–30.

Scurlock, J. 2006. Magico-medical Means of Treating Ghost-induced Illnesses in Ancient Mesopotamia. Leiden: Brill.

State Archives of Assyria Online, The SAAO Project, a sub-project of MOCCI.

Want To Learn More?

Concepts and Metaphors in Sumerian

By Erika Marsal

Sumerian was a language used in southern Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) from ca. 3000 BCE to ca. 1800 BCE. Despite the numerous attempts to relate Sumerian with other languages, it is still, as far as we know, unconnected with any other known language, dead or alive. Read More

Epidemics in Mesopotamia

By Annie Attia

Epidemics have been with us since long before the dawn of history, commonplace phenomena that help us to locate ourselves in the stream of time. Here is what we know about their occurrence in a cradle of civilization, in Mesopotamia. Read More.

Psychedelics and the Ancient Near East

Psychedelics and the Ancient Near East

By Diana L. Stein

As courts today debate whether to legalize or regulate the use of drugs like cannabis, it is interesting to look at the history of man’s relationship with mind-altering substances… Yet, despite the consensus that “every society on earth is a high society,” the ancient Near East is omitted from these surveys. Is it too remote? Do we know so little? Was it unique? The evidence suggests otherwise. Read More