INCIDENT REPORT FEATURE: BORSIPPA

U. S. DEPT. COOPERATION AGREEMENT NUMBER: S-IZ-100-17-CA021

BY Jamie O’Connelll

Locals decry condition of archaeological site

* This report is based on research conducted by the “Safeguarding the Heritage of the Near East Initiative,” funded by the US Department of State. Monthly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change.

The site of Borsippa (or Birs Nimrud) was an important Sumerian site located 18 kilometers southwest of Babylon. Occupation began at least as early as the Ur III period (ca. 2112–2004 BCE) and continued through the Seleucid era (ca. 3rd century BCE). Borsippa is known for its distinctive ruined ziggurat, which contained a temple dedicated to the god Nabu that was built in the 6th century BCE on the remains of an older structure from the mid-2nd millenium. The ziggurat originally stood at 75 meters tall and consisted of seven terraces [1].Borsippa is also known for the cuneiform tablets discovered in great quantities at the site, many of which have been sold on the antiquities market [2].

Excavations began at Borsippa in 1854 under H.C. Rawlinson [3]. Between 1879 and 1881, the site was excavated by Hormuzd Rassam for the British Museum [4]. In 1902, Robert Koldewey dug at the site under the auspices of the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (German Oriental Society). Beginning in 1980, an Austrian team led by Helga Piesl-Trenkwalder and Wilfred Allinger-Csollich from Leopold Franzens Universität Innsbruck conducted excavations for 16 seasons [5].

View of remains of the Borsippa ziggurat (Ancient History etc; November 11, 2014)

A view of the upper section of the Borsippa ziggurat, with metal support beams (Facebook/Ishtar Gate; August 27, 2015)

In December 2013, heavy rains revealed over 200 artifacts, including clay tablets and pottery sherds dating to the Babylonian era, as well as gold and silver coins from later periods. In February 2016, rains again revealed dozens of artifacts dating to the Old Babylonian and later periods, including small clay amphorae and oil lamps, seals, and coins.

A collection of artifacts recovered in 2016 from Borsippa (Al Sumaria; February 11, 2016)

A collection of small amphorae recovered from Borsippa in 2016 (Al Sumaria; February 11, 2016)

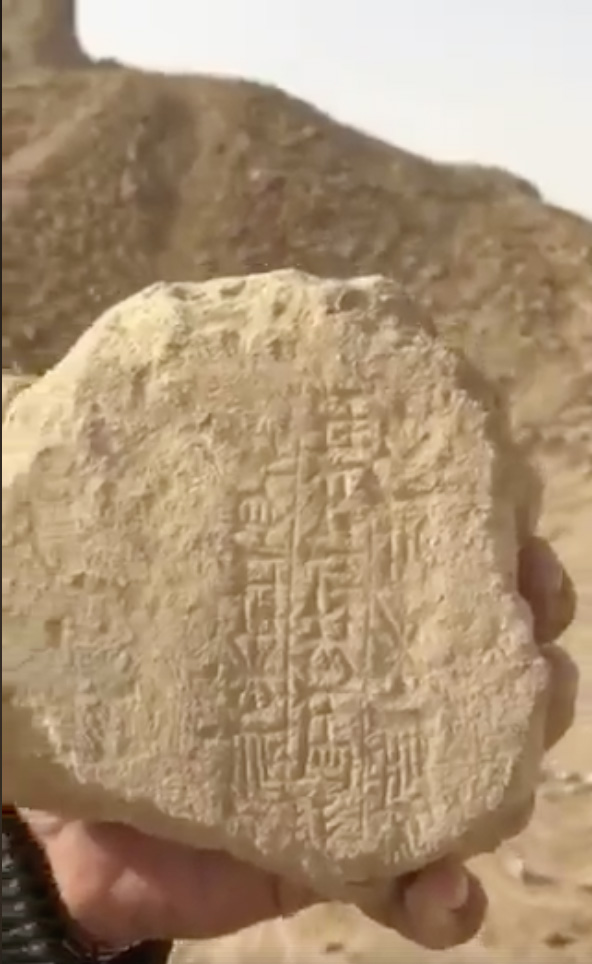

A visitor to Borsippa holds a piece of a mudbrick inscribed with cuneiform discovered on the surface of the site (Iraq museum المتحف العراقي; January 21, 2018)

Fragments of cuneiform-inscribed bricks are found on the surface of Borsippa (Iraq museum المتحف العراقي; January 21, 2018)

In late February 2018, following another period of heavy rain, around 70 artifacts (dating to the Parthian era and later) were recovered from the site by a joint team from Iraqi National Security, the Antiquities Department, and police from Babil Governorate. The artifacts will be analyzed and handed over to the Iraqi Museum in Baghdad for further study.

Iraqi authorities display a number of artifacts recovered from Borsippa after heavy rains (Baghdad News; February 27, 2018)