UPDATE: MOSUL POST-ISIL: HERITAGE DESTRUCTION AND THE FUTURE OF THE CITY

U. S. DEPT. COOPERATION AGREEMENT NUMBER: S-IZ-100-17-CA021

BY Michael Danti, Kyra Kaercher, Allison Cuneo, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, and Gwendolyn Kristy

* This report is based on research conducted by the “Safeguarding the Heritage of the Near East Initiative,” funded by the US Department of State. Monthly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change.

The Battle for Mosul

On July 10, 2017, Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi announced Iraq’s victory over ISIL in the militant group’s former northern Iraqi stronghold of Mosul. His announcement followed months of fighting, extensive aerial bombardment, massive infrastructure damage, human displacement, and thousands of civilian casualties. The struggle for Mosul spanned nine months, with the most intense fighting occurring in the labyrinthine confines of the Old City. The final month of military operations brought the worst damage and high numbers of civilian casualties as ISIL militants unleashed waves of car bombings, suicide bombers, and snipers to target both Iraqi forces and Mosul residents. As of the publishing date, Iraqi forces continued clearing operations, rooting out final pockets of ISIL fighters concealed amid the rubble of once bustling neighborhoods.

Throughout its long history, Mosul and its precursors such as Nineveh have served as key economic and agricultural hubs on the northern Iraqi plain, occupying a strategic location along the Tigris River. In 2014, Mosul contained a population of almost two million comprising several major ethnic groups, including Arabs, Kurds, Assyrians, Armenians, and Turkmen. Diverse religions also co-existed with communities of Sunni, Shia and Sufi Muslims; Orthodox, Catholic, and Assyrian Christians; a Jewish population; and a small Yazidi population, making Mosul one of Iraq’s most diverse cities. The discovery of oil in northeastern Iraq in the 19th century transformed the city into an economic capital. With the founding of the University of Mosul in 1967, the city became a cultural capital for much of northern Iraq. The University is world renowned, and considered one of the premiere institutions in the Middle East. Such preeminence has earned Mosul the moniker of “Iraq’s Second City”.

ASOR CHI has monitored recapturing operations in Mosul and has documented damage to dozens of cultural heritage sites. As of July 12, 2017, we have reported 87 individual incidents of damage to religious heritage including mosques (47 incidents), churches (26 incidents), shrines (10 incidents), and cemeteries (4 incidents). We have reported 42 individual incidents of damage to secular sites, including University buildings (23 incidents), libraries (8 incidents), museums (4 incidents), and other buildings (7 incidents). Lastly, we have documented 27 individual incidents of damage impacting archaeological sites, including 24 at Nineveh and one each to Bashtapia, Qara Serai, and Deir Mar Elia. In all, ASOR CHI has recorded damage to 102 individual sites in Mosul, and the number is rising as more photographs and videos are released from liberated regions.

The Cultural Casualties of War

Habitation in the Mosul area stretches back to around 6000 BCE. The city is perhaps best known for the ancient site of Nineveh, the former capital of the Assyrian Empire (911–612 BCE). During the Islamic Period (ca. 600 CE–Present), Mosul has served as the seat of various dynasties. Mongols conquered the city in 1262 CE. In 1555 CE, the city fell under the control of the Ottoman Empire. In its more recent history, Mosul was has been a city of diversity, with many of Iraq’s minority populations coexisting. The city is also home to Mosul University (founded 1967 CE) — the second largest university in Iraq — and the Mosul Museum established in 1952.

The Old City of Mosul, located on the Western Bank of the Tigris, dates back to the Zengid Dynasty (1127–1250 CE) with historic suqs, mosques, churches, and government buildings dating from 1200–1800 CE. In June 2014, a force of about 1,000 ISIL militants invaded the city.

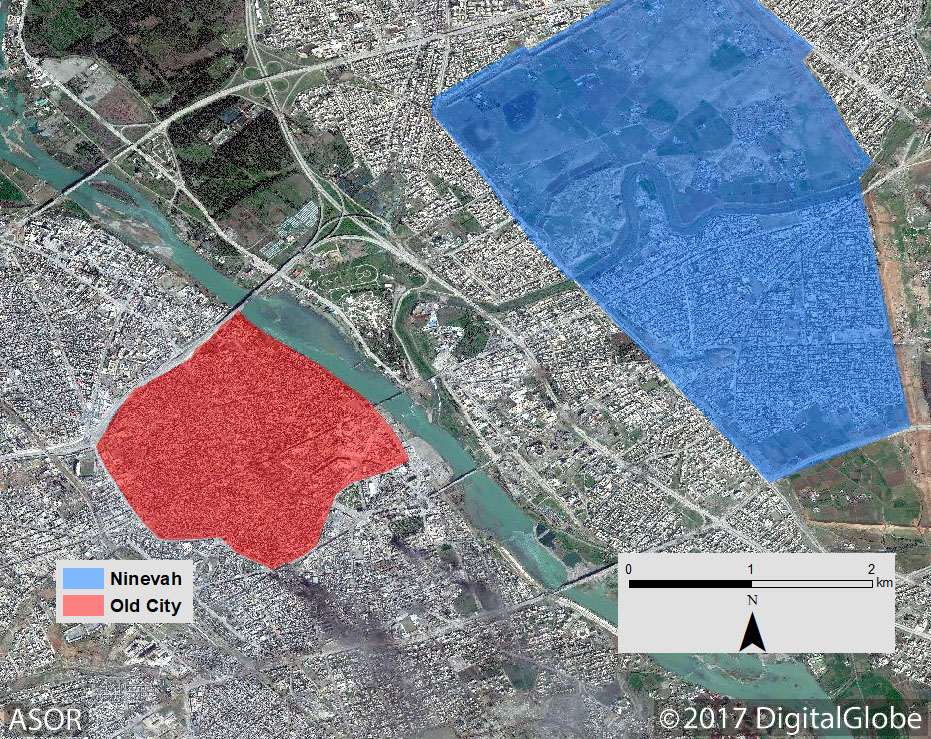

DigitalGlobe Satellite Imagery shows the location of Nineveh (blue) and the Old City (red) (DigitalGlobe; July 2017)

Between June 2014 and late December 2015, ISIL carried out multiple intentional destructions of major cultural heritage sites across Mosul. ISIL destroyed shrines, graveyards, and mosques because they believe people are praying to the people buried there instead of only to Allah — such supposed intercession is contrary to their beliefs. al-Arabiya reported on July 5, 2014 that four shrines to Sunni Arab or Sufi figures as well as six Shia mosques were destroyed across northern Ninawa province. They report that Sunni and Sufi shrines were bulldozed, while Shia mosques and shrines were destroyed by explosions. On July 29, 2014 the Assyrian International News Agency (AINA) reported that ISIL had destroyed or occupied all 45 Christian institutions in Mosul. While later evidence confirmed that not as many sites were destroyed as originally reported by news organizations and in social media, all churches sustained some type of damage or occupation between 2014–2017. ASOR CHI has confirmed the total destruction of 32 religious sites, including shrines, mosques, churches, and cemeteries during ISIL’s three-year occupation. ISIL forces intentionally damaged Mar Ahudemmeh, Kanisat al-Sa’a, and the Church of the Holy Spirit. The destructions of al-Nuri al-Kabir Mosque and al-Habda Minaret were ISIL’s final intentional destructions in Mosul and represent cruel acts of retributory violence.

An aerial view of the remains of al-Nuri al-Kabir Mosque and al-Hadba Minaret (AP; July 6, 2017)

ISIL also intentionally destroyed or repurposed places of higher learning, including universities and libraries. Beginning in 2015, ISIL looted Mosul University and repurposed it as a teaching facility and munitions factory. Militants burned other education buildings that were either unused or deemed heretical. ISIL looted and vandalized the Mosul Central Library in 2014 and 2015, burning large parts of the library’s collections. The same fate befell Mosul University Library, where ISIL militants looted and burned books. The destruction to Mosul’s educational and cultural infrastructure promptedUNESCO General Director, Irina Bokova, to condemn the destruction stating, “this destruction marks a new phase in the cultural cleansing perpetrated in regions controlled by armed extremists in Iraq. It adds to the systematic destruction of heritage and the persecution of minorities that seeks to wipe out the cultural diversity that is the soul of the Iraqi people.”

ISIL also targeted Mosul’s archaeological heritage. The Assyrian site of Nineveh was looted by the group during their three-year occupation. Nebi Yunus, also known as the Tomb of Jonah, was destroyed by ISIL in 2014. Following the recapture of the area in 2017, various sources revealed, that ISIL had tunneled under the site into a Palace of the Assyrian king Esarhaddon in order to loot antiquities. The Mosul Museum was looted and vandalized in 2015. In 2016, the militants leveled the monumental Adad, Mashki, and Nergal city gates and destroyed sculptures inside the structures. ISIL dismantled the Palace of Sennacherib (the Southwest Palace) in 2016 and constructed a new road across the southern part of the archaeological mound which began in 2015 and was completed in 2016.

Intentional damage to Nergal Gate (Amaq News Agency; June 7, 2016)

Palace of Esarhaddon underneath Nebi Yunus (Yahoo News; March 7, 2017)

The start of the offensive to liberate Mosul led to an increase in military related damage to heritage sites. The US-led Coalition heavily bombed Mosul University in 2016, targeting 19 of the university’s buildings that were being used by ISIL. ASOR CHI recorded a total of 28 buildings damaged by military activity in 2016.

Damage to Headquarters of the President of Mosul (Amaq News Agency; March 21, 2016)

In 2017, Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) recaptured Mosul’s Eastern Bank and military operations turned to the Old City, ISIL’s last bastion. Since January 1, 2017, ASOR CHI has reported military damage to 57 heritage sites, 52 of which are located on the city’s West Bank. Due to ISIL’s media blackout, it is currently unclear when much of this damage occurred. The UN reports that 5,000 buildings were damaged and 490 were destroyed in the Old City alone, “The city’s basic infrastructure has also been hard hit, with six western districts almost completely destroyed and initial repairs expected to cost more than $1 billion, the United Nations estimates.”

Vandalism and theft as well as development threats to sites were not new issues when ISIL took control of Mosul. By 2010, modern development covered almost 40 percent of Nineveh, and looting was on the rise due to instability linked to insurgents. Caches of artifacts and other cultural property have begun appearing in liberated houses across Mosul, including natural history specimens, artifacts from museums and local archaeological sites, and books from libraries.As ASOR CHI has documented elsewhere in Iraq and Syria, liberation from ISIL does not end vandalism and theft. Recent photographs from al-Hadba Minaret show graffiti linked to Iraqi Security Forces (ISF).

A view of some of the 490 destroyed building in the Old City (BBC; July 10, 2017) From front to back – Bab al-Tub Mosque , Mosque of the Pasha, ‘Abdal Mosque, al-Tahira Church, Archbishopric of Catholic Church

The Future of Mosul

Emergency response and longer term reconstruction projects for historical and archaeological heritage may only move forward in lockstep with restoring basic human services and critical infrastructure. As a result of the ISIL occupation and the subsequent military campaign, Mosul has lost reliable electricity, sewer systems, waste disposal, drinking water, bridges, schools, and its airport. The United Nations has reported that of the 54 residential districts in the western half of Mosul, 15 are heavily damaged and at least 23 are moderately damaged. An estimated 900,000 people of Mosul’s 2 million person population remain displaced. Of those displaced, around 200,000 now lack homes. Reconstruction estimates reach upwards of 100 billion dollars with a time-frame of ten years to return Mosul to the condition it was before the ISIL occupation.

Mosul is one of the largest Sunni majority cities in a largely Shia majority country. In the past, the lack of Sunni Muslim governance in the Shia-led government has been a source of tension and conflict. Under Saddam’s rule (1979–2003), Arabs from the south of Iraq were resettled in Mosul, pushing out an estimated half million Kurds from Ninawa Governorate. In 2007, the Kurdish coalition held 31 of 41 seats even though Kurds made up only 35 percent of the population of Ninawa Governorate. Tensions were running high between these different groups, and ISIL exploited these ethno-sectarian tensions to recruit Sunni Arabs to their cause. Under ISIL’s rule, most Shia, Christians, Kurds, Yazidis and other religious and ethnic groups targeted by ISIL fled Mosul under the threat of death.

al-Hadba Minaret with Iraqi forces in front and graffiti present (Private Facebook Account; July 8, 2017)

Mosul has now been liberated by a mixed group of Shia and Sunni Iraqi security forces, Shia Popular Mobilization Front (PMF) units, Kurdish Peshmerga Forces, and Iraqi-Christian militias. These different groups continue to control different neighborhoods in Mosul and the surrounding countryside. The sectarian nature of some of these armed groups has led to concern among the Sunni population of the city that sectarian retributory constitutes a major risk. After the capture of Tikrit and Fallujah, Shia militia members were accused of conducting sectarian revenge killings, as well as intentional destructions of Sunni religious sites, homes, and businesses. As the PMF remains an official branch of the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF), under the auspices of Baghdad, concern runs high as to the level of impunity these forces may enjoy.

On the Kurdish front, Peshmerga forces are reluctant to return Iraqi territory captured in their efforts to push ISIL from the Nineveh Plains. Iraqi officials as well as Ninawa Governorate residents have already voiced concern that Kurdish forces may be attempting to hold the area in order to gain territory and exert political leverage. Lt. Gen. Stephen Townsend, Commander of the Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve, has already cautioned that in order to keep “[ISIL] 2.0 from emerging, the Iraqi government is going to have to do something pretty significantly different” to avoid the same sectarian tensions that led to the fall of Mosul in 2014 and the rampant expansion of ISIL.

With the defeat of ISIL and the return of Iraqi governance, suicide bombings are on the rise and some experts predict a return to the low-level insurgency prominent in Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003 that continued up until 2014. In addition to immediate challenges, longer term issues related to Mosul’s governance and political control of neighboring regions are still under negotiation.

The toll of the war on civilians is staggering. A generation of Iraqis have now grown up under the instability of the post-Saddam era and the atrocities of the Islamic State. In the battle to recapture Mosul, ISIL used civilians as human shields and targeted anyone attempting to flee, resulting in a traumatized population, many whom are now displaced. In Haider al-Abadi’s July 11 victory speech, he called for the unification of Iraq and lauded the victory over ISIL as one for Iraq by Iraqis. He further stated that the unity achieved to defeat ISIL must continue to rebuild the country. UN special representative Jan Kubis expressed his strong belief that any reconstruction work must run parallel to “robust political process to conduct elections and achieve national and societal reconciliation and rebuild the social fabric…The peace… must be based on solid foundations of unity, co-operation, justice, tolerance and coexistence starting at the societal, community and tribal levels to prevent falling back into the past and risk disastrous consequences.” Mosul’s cultural resources and cultural sector form integral and inextricable parts of such reconciliation and peacebuilding efforts.

Students sort books at Mosul University (Buzzfeed; July 2017)

Despite months of horror and fear, hope still remains among Mosulis in recaptured areas. In eastern Mosul, people are returning to rebuild their lives. They are returning to their jobs, and the government is repairing roads and infrastructure to facilitate resettlement. In April 2017, professors and students of Mosul University started to clean and repair buildings in anticipation of resuming classes in the fall semester. All professors were advised to return to Mosul after exams, which were given in Mosul U’s temporary campuses Dohuk and Kirkuk in the Kurdistan region. The exams were held in mid June, so the professors have time to prepare themselves and the university for the new school year, beginning in September. Rebuilding the libraries has started, with donations of hundreds of books coming from Marseille, Bibliotheca Alexandria, Basra University, and Dijlah University College, as well as from organizations from around the world. With a unified effort from all groups who live in Mosul and robust international support, Mosul will rise again to become northern Iraq’s premiere city.

Future ASOR CHI Efforts in Mosul

ASOR CHI will work closely with Iraqi cultural heritage personnel to support their efforts to rehabilitate Mosul’s cultural resources and infrastructure and to rejuvenate the cultural and educational sectors generally. Success depends on providing a broad-base of support to Iraq’s heritage experts and local stakeholders as soon as possible. In the coming months, ASOR CHI will implement new emergency response projects to repair damaged heritage sites and to mitigate threats to cultural assets in cooperation with Iraq’s State Board of Antiquities and Heritage. In addition, we are currently launching a project to inventory and digitally preserve textual collections and collections management data in the city as part of a joint effort bringing together various Iraqi authorizing agencies and private institutions, the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library, and the Centre Numérique des Manuscrits Orientaux . This effort is supported through a generous grant from the Whiting Foundation.

Since 2014, ASOR CHI has worked closely with our Iraqi colleagues to provide them with assistance and to expose the atrocities committed in northern Iraq to the world. We hope that the future holds peace and prosperity for Iraq, and ASOR CHI will continue to assist Iraqis in preserving and protecting cultural heritage. We will never forget the cherished friends and colleagues that we have lost in Mosul, nor the tragedy that has befallen this vibrant and ancient city.