Absences, Archaeology, and the Early History of Monotheistic Religions in the Near East

February 2023 | Vol. 11.2

By Robin Derricourt

In my writing I use archaeology and history together to understand phenomena of the deep past. I have authored survey volumes on interpretations of Africa’s deep past, on our knowledge of children and childhood in prehistory, and under the title Antiquity Imagined, on some illusory constructions of the ancient Near East. For my most recent book, Creating God: the Birth and Growth of Major Religions, I took a strictly secular approach to consider how archaeological evidence complements historical texts on the ever-fascinating topic of major monotheisms.

In this project, I was struck by two themes. In some contexts, the absence of archaeology plays an important role in what we might understand. But in other contexts it is the archaeology of absence that tells us what we need to know. By the archaeology of absence, I mean that when decades of thorough and careful archaeological fieldwork did not turn up what might have been expected, that absence gives us important information. The long sequence of archaeological work in the Near East and Mediterranean region provides some examples.

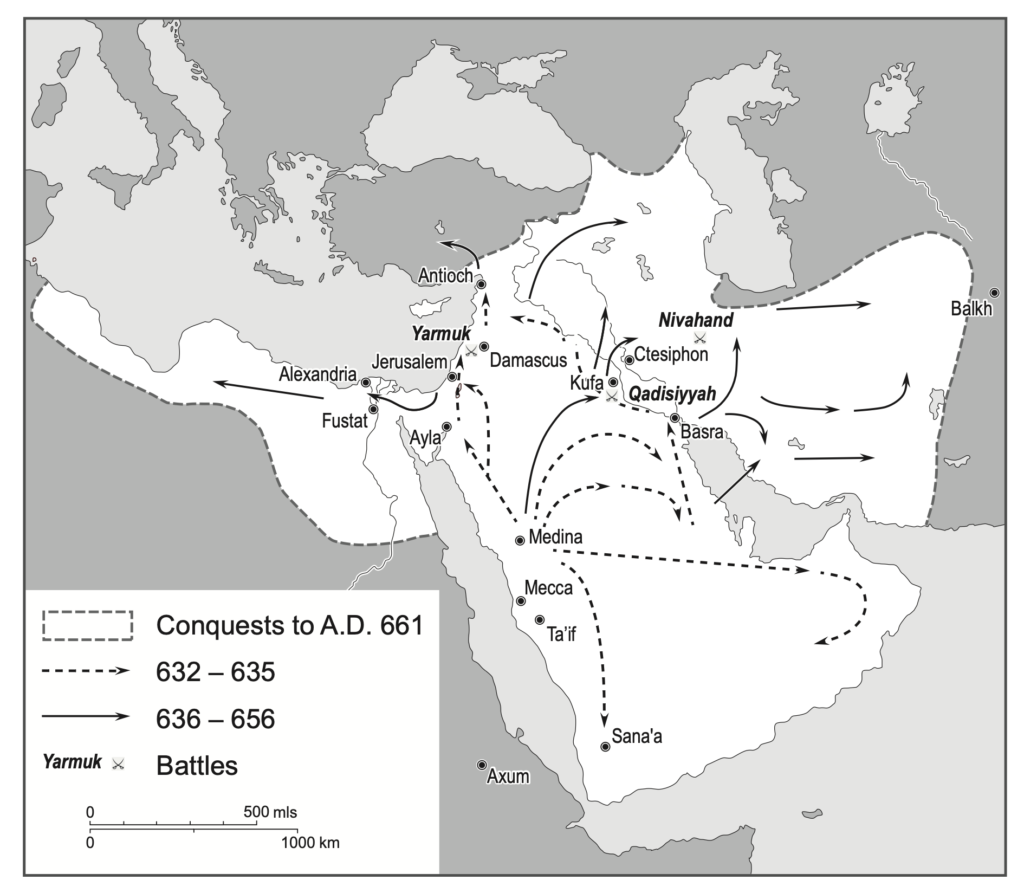

Campaigns of the Islamic Arab armies in the Middle East in the early 7th century CE (from Derricourt, Creating God)

When the conquerors from the Arabian Peninsula, united by their new Islamic faith, seized the territories of the Byzantines and Sasanian Persians in the 7th century CE, the historical record might imply a dramatic change to the lives, the material culture and the economies of conquered peoples. But the substantial and continuing archaeological research through the Levant (Syria, Jordan, Israel and the Palestinian territories), as well as in some other regions, shows an absence of such impacts. Pottery in formerly Byzantine-ruled areas continued to be in the same styles as before; Jewish synagogues and Christian churches continued to be used and indeed expanded, and transformation into what we call Islamic culture was initially slow and unforced. History spoke of the dramatic defeat of mighty empires; archaeology suggests continuity, as traders continued trading and farmers continued farming, with taxes now paid to a different set of rulers, who often created their own separate settlements as well as new buildings in major towns.

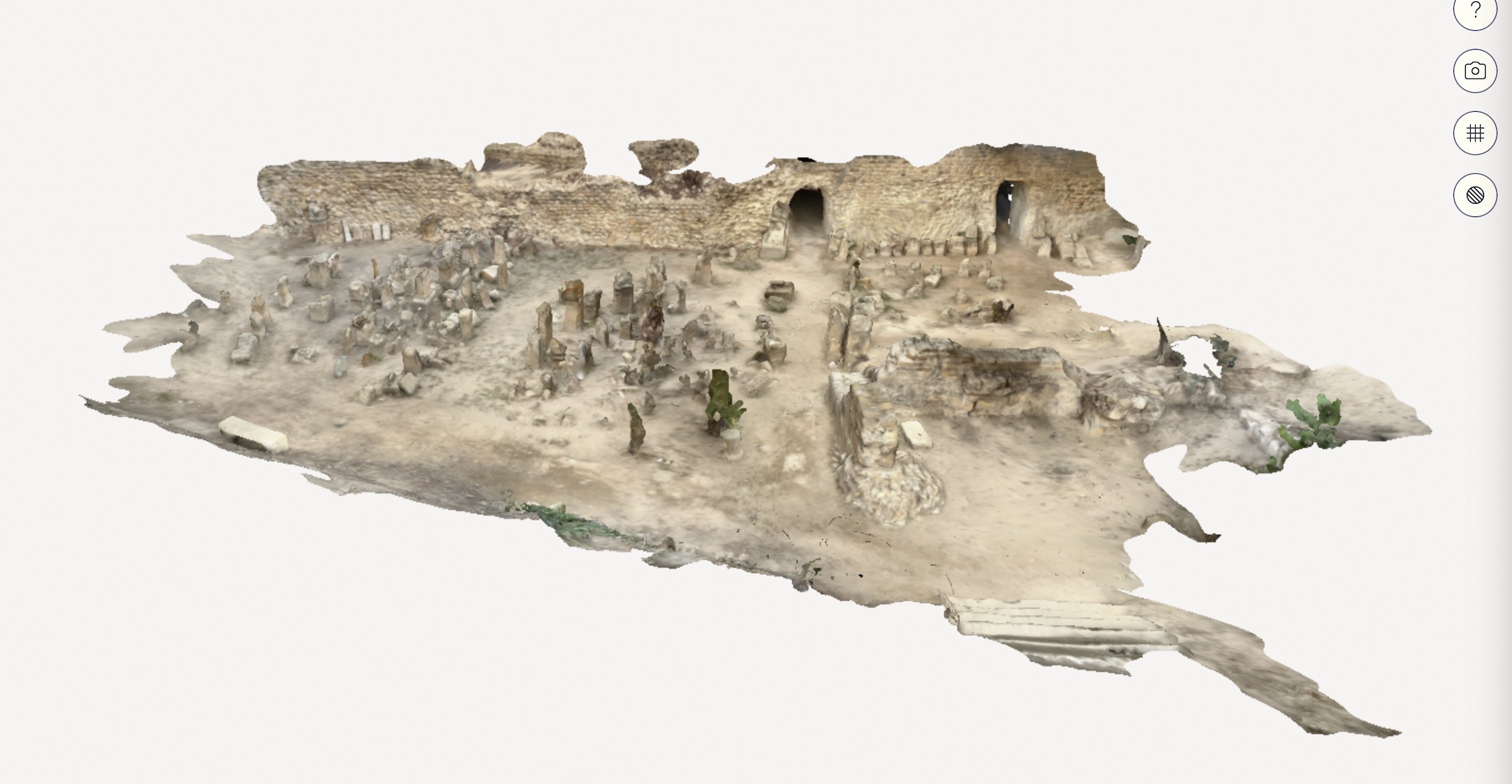

Beit She’an in Israel where Byzantine Christianity flourished after the Islamic conquest (Photo by Author).

The long and well established field under the name of “Christian archaeology” includes the study of religious buildings, burials, inscriptions, art and other evidence of the history of Christian communities. And while one might expect to see markers of Christian identity in its initial centuries, here too, a century and a half of intensive field research, survey, excavation and study has revealed the absence of Christian inscriptions or symbols such as the cross or fish in the first and second centuries. Only from the 3rd century onwards do we begin to see burials identifiable as Christian. Most Christian archaeology is, in fact, the study of sites which developed after Christianity was proclaimed a tolerated then official religion by the Emperor Constantine after the year 313. The failure to uncover evidence of significant Christian communities in the first two centuries CE suggests slow growth in widely distributed small communities of Christian believers.

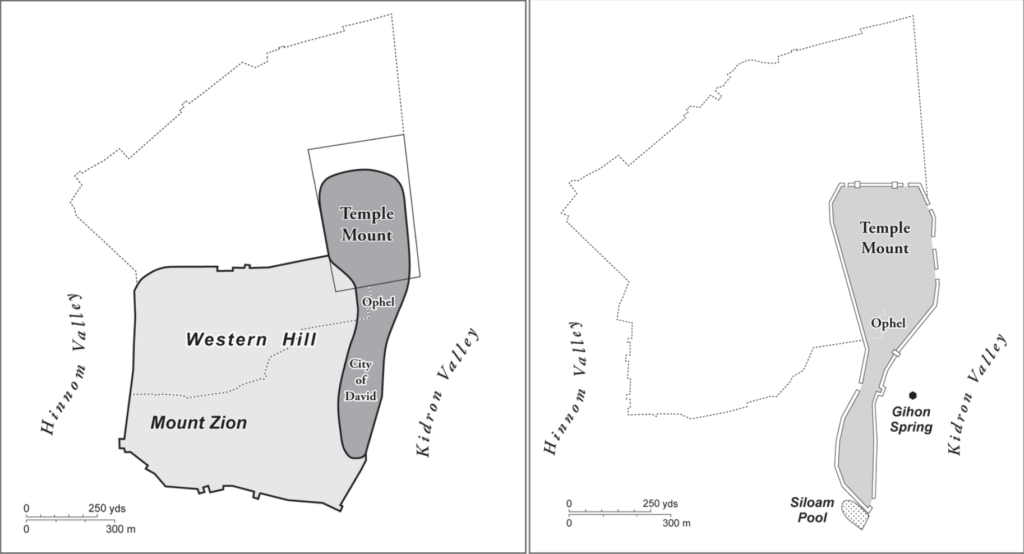

(Left): Jerusalem on the eve of the Babylonian Conquest (from Derricourt, Creating God).

(Right): Jerusalem in the later Persian Period (from Derricourt, Creating God).

Few areas have seen as much professional archaeological research as Israel, with Jerusalem of particular interest. But while Jerusalem is central to Old Testament narratives of the Jewish people, a much more nuanced picture of its history has emerged through the studies of recent years—though not without some engaged debates. The city of David and Solomon and the later kings of Judah was conquered by the Babylonians at the beginning of the 6th century BCE and largely depopulated, with the administrative centre moved away to the north. After the Persian ruler Cyrus allowed Jewish exiles in Babylonia to return to Judah, archaeological evidence suggests only a few hundred families lived in Jerusalem. But it was this group which is credited with the development of strictly monotheistic Judaism, its practices, with a focus on the Jerusalem temple, and the compilation and editing of the Tanakh, the Old Testament. The importance of Jerusalem to religious traditions cannot be overestimated, but to archaeology it was long a small settlement in an arid and marginal region under the control of Persian and then, after the conquests of Alexander, Hellenistic rule.

So, we have three examples where the archaeology of absence affects how we see the beginnings of major religions. What about my other theme, the absence of archaeology, gaps in the story? This, perhaps inevitably, reflects different religious sensitivities which are, in turn, shown in the cautious approaches of political authorities.

The exciting and important new excavations at the Church of the Sepulchre in Jerusalem are on a site considered by many (if not all) Christian churches as the site of Jesus’ execution and also his burial. But the Christian religious authorities who share responsibility for the site have been supportive of the archaeological work, which is expected to reveal more detail of the construction from the Constantine era onwards.

But elsewhere in Jerusalem at the Temple Mount—the Haram al-Sharif—religious and political sensitivities over one of the most contested sites in the region mean archaeological excavation is not an option. This was the location of the temple developed during the period of Persian rule, and substantially expanded by Rome’s client king Herod; in Jewish tradition it was the site of a major temple built by King Solomon. Here also are the al-Aqsa mosque begun in the 630s and the Dome of the Rock from the 680s, marking the site as one of the most sacred in Islam. A large open space in front of these buildings is unoccupied. The absence of archaeology leaves the deep history of this crucial zone unclear but avoids potential tensions over what might, or might not, be uncovered.

Another place where archaeological excavation would be fascinating is the Muslim holy city of Mecca, the birthplace of the prophet Muhammad. The traditions that developed in Islam suggested ancient Mecca had been a major trading and religious centre but independent evidence for that is lacking. Although archaeology is developing vigorously in Saudi Arabia, excavation has not extended to test the historical realities of Mecca nor is it permitted in the other holy centre of Medina. Faith and tradition therefore remain neither endorsed nor denied by archaeological work.

Archaeology can confirm the traditional views of a religious, national or ethnic group; it can refine them; or it can provide a different story. Where archaeology is absent, traditions remain neither proven nor eroded. Where archaeology is present and an expected result is absent, we need to change our assumptions and interpretation. In writing my book on the first stages of major monotheistic religions I found the central role of archaeology fascinating and important. But as with any scientific discourse, one new archaeological discovery, one new scientific test, one new means of analysis can change our thinking further.

Dr. Robin Derricourt is Honorary Professor of History at the University of New South Wales. His books include Creating God: the Birth and Growth of Major Religions (Manchester University Press), and Antiquity Imagined: the Remarkable legacy of Egypt and the Ancient Near East (IB Tauris).

How to cite this article

Derricourt, R. 2023. “Absences, Archaeology, and the Early History of Monotheistic Religions in the Near East.” The Ancient Near East Today 11.2. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/derricourt-absence-archaelogy-monotheism/.

Want to learn more?

The Amorites: Rethinking Approaches to Corporate Identity in Antiquity

Putting Carthaginian Stelae Back Into Context: The ASOR Punic Project Digital Initiative

Post a comment