Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

June 2023

Vol. 11, No. 6

Baths of the Roman and Byzantine Southern Levant: Roman Ideas and Local Interpretations

By Arleta Kowalewska and Craig A. Harvey

Bathhouses are one of the most iconic remains associated with the Roman world, easily recognized by their distinctive double floor (called “hypocaust”, meaning “place heated from below”) and wall heating system. Public bathing in warm-water baths was one of the pillars of the Roman culture — these bathhouses provided not only a variety of hygienic services, but also a space for socializing and entertainment. As Roman hegemony spread to the Near East starting in the 1st century BCE, so too did the practice of Roman bathing. Bathhouses became a ubiquitous feature of the provincial landscape, being built as public or private facilities in cities, towns, villages, road stations, and military enclosures (fig. 1).

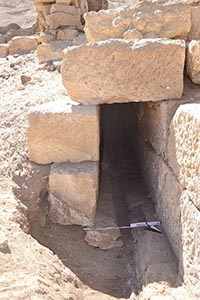

Other 1st century CE private bathing suites come from securely recognized and dated contexts all around the Herodian Kingdom, such as at Ramat haNadiv, attesting to this luxury being popular before Jerusalem’s fall in 70 CE (fig. 4). Those with fewer funds had to make do with public bathhouses, but when these public facilities were introduced is still an open question. Two public establishments excavated in a settlement on the outskirts of ancient Jerusalem were in use from around the year 70 CE, but those found in Magdala or Capernaum may be even earlier. East of the Jordan River, in the modern nation of Jordan, foreign and local archaeologists have brought to light bathhouses and bathing suites of the Nabataeans (fig. 5), many of them probably built before 106 CE when the Romans took direct control. Some of these bathing facilities may have been constructed shortly after the baths built by Herod the Great in his residences. It is hard to assess the extent to which Herod’s baths influenced those of the Nabataeans, as we have not yet pinpointed the dating of the Nabataean villa and road-station baths.