Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

May 2023

Vol. 11, No. 5

Dig Deeper: Revisiting the Excavations of a Glass Workshop at Jalame el-Asafna

By Katherine A. Larson

How was glass made in antiquity?

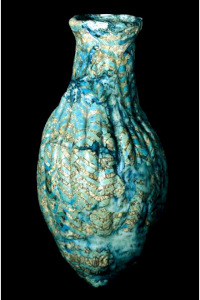

Waste from glassblowing found at Jalame, Israel, made between 350 and 400 CE. (L.128.1.2018-643, lent by the Israel Antiquities Authority.) Image courtesy of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

This is the question that drove a team from The Corning Museum of Glass and the University of Missouri to undertake the first focused scientific excavation of a Roman-period glass workshop at the site of Jalame el-Asafna in the 1960s, and it continues to motivate ancient glass studies today. The resulting excavations, and what we have learned since, are now the focus of a temporary exhibition at The Corning Museum of Glass.

Jalame el-Asafna is located about 10 mi / 15 km southeast of the city of Haifa at the foot of Mount Carmel in modern Israel. While it is now known to archaeologists and glass specialists as a late-4th century glass workshop, in the late Ottoman and British Mandate period it shared a name with a nearby village whose Palestinian residents were forced to leave when Israel was founded in 1948.

The work at Jalame el-Asafna led to the publication in 1988 of Excavations at Jalame: Site of a Glass Factory in Late Roman Palestine — the first monograph dedicated to an ancient glass workshop site. This was a collaborative effort, accomplished under the intellectual leadership of Gladys Davidson Weinberg, with scientific contribution by Robert Brill, typological study by Weinberg and Sidney Goldstein. The publication was enhanced through consultation with Dominick Labino, a major figure in the Studio glass movement who looked to ancient technology as inspiration for glass as an art form independent of industrial production.

Red Room from South. Jalame, 1966. Image Courtesy of Museum of Art and Archeology, University of Missouri.

Yet challenges with the stratigraphy, significant disturbance in the location of the glass furnace (the “Red Room”), and overall lack of comparative glass workshop data available the time meant that key questions about the appearance and operation of the furnace and the mechanics of glass production — by Weinberg’s own admission — remained unresolved. However, a new exhibition on the Jalame glass workshop at the Corning Museum of Glass (opening this month) has provided us the opportunity to revisit those issues.

We now recognize that a large villa with oil and wine presses was built over the glass workshop, probably in the 5th century. These villa builders likely also cleared the site, discarding the glass workshop remains off the southwest edge of the hill in the glass dump documented by the Corning-Missouri team. The glass made in the workshop, however, is firmly mid to late-4th century, as has been borne out by studies of glass elsewhere in the region.

So where did the glass workers go? Probably not far: in the 60 years since the Jalame excavations, dozens of other late antique glass workshops have been found up and down the Levantine coast. None of these workshops lasted for very long, but following the Jalame pattern may have operated for as little as 5–10 years. The glass workers probably moved as their furnaces reached the end of their use life (even today, glass furnaces rarely exceed 10 years of usage due to corrosion between the molten glass and ceramic refractory of the furnace linings) and readily available fuel had been consumed.

Among those dozens of additional workshops is one at the northwest side of the Jalame el-Asafna hill, along a railway line connecting Haifa and Bet She’an. The 2015–2016 IAA salvage excavations identified remains of two pairs of tank furnaces for raw glass manufacture, along with glazed and fired bricks, furnace waste, and assorted other workshop debris similar to what the Corning-Missouri team had found.

This information has led to a reappraisal of the Red Room as a primary tank furnace, where raw glass was produced from constituent ingredients of local sand and natron imported from Egypt. A smaller secondary glassblowing furnace must have been located nearby, as waste products like moils found in the earlier excavations are consistent with vessel forming.

Recent scientific analysis conducted by Gry Barfod and Ian Freestone, updating and expanding Brill’s work from the 1980s, has confirmed a Levantine source for the sand. Yet other material sources seem to be shifting, pointing the way toward the manufacturing trends of late antiquity: Jalame glass does not contain antimony as decolorizer, which is characteristic of first-to-third century Roman glasses, and the trace elements associated with cobalt are consistent with the cobalt used much later, in the sixth century, rather than the earlier Roman source.

Jalame therefore joins Apollonia, Bet Eli’ezer, and Bet She’an as a small group of known locations in late antique Palestine which was producing raw glass. Diocletian’s Prices Edict of 301 clearly distinguishes between “Judean” and “Alexandrian” glasses, with the former being cheaper and lower quality (a third category of window glass was the cheapest of all). Scientific analysis has confirmed this; throughout much of the Roman and late antique periods, glass seems to have been made in a few locations in Egypt and the coastal Levant, from where it traveled in the form of small chunks through the Mediterranean shipping networks throughout the Empire.

As these trade routes deteriorated in late antiquity, glass became increasingly hard to source in the west yet remained abundant in the east. Yet this moment was yet to come: some fourth-century glass found in Europe is consistent with Jalame composition, suggesting that the site briefly reached much wider markets. By comparison, the work of the glassblowers did not go nearly as far, supplying instead a local and regional utilitarian market for daily household and funerary use.

From Excavation to Exhibition

Recalling the origins of the Jalame excavation decades later, Paul Perrot, at the time Director of the Corning Museum of Glass, stated that contrary to the expectations of many museums, the project was not concerned with “finding objects that would delight the eye,” but rather those that “showed promise of providing data on the technology of glassmaking in antiquity.” This proved to be a challenge as I began plans to mount an exhibition focused on the discoveries at Jalame and their importance to archaeology and ancient glass studies! As an archaeologist, I found the large fragments of vessels, huge chunks of glass, remains of the furnace, and thousands of pieces of waste from the glassblowing process incredibly informative and compelling. But as a curator, I recognized that they subverted the typical aesthetic preferences of museums and would be difficult to comprehend for a non-specialist in ancient glass.

To solve this issue, we took several approaches. First, we emphasized that the exhibition is largely about process: how do archaeologists forensically examine these seemingly unremarkable pieces to build knowledge about the past? The exhibition focuses primarily on the work that happens after the excavation, in the laboratory and in ongoing conversations with specialists in other fields — in this case, glass artists like Dominick Labino. In doing so, we undermine the predominant popular narrative of archaeologists as Indiana Jones-like figures.

Installation views of Dig Deeper: Discovering an Ancient Glass Workshop at The Corning Museum of Glass. Images Courtesy of The Corning Museum of Glass.

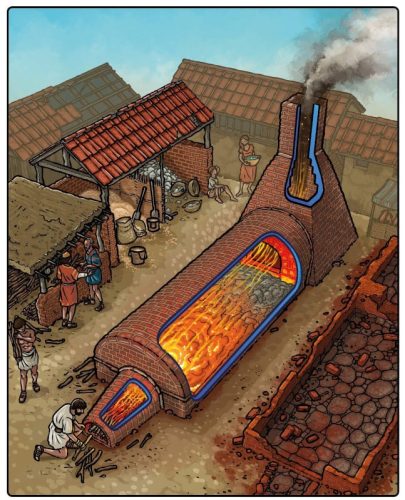

Second, we deployed several interpretive strategies to help visitors better understand what they are looking at and think like an archaeologist. A dedicated wall of cases juxtaposes vessel fragments found at Jalame with similar intact objects from other excavations on loan from the Israel Antiquities Authority Department of National Treasures and from The Corning Museum’s permanent collection. A series of illustrations by John Swogger showing the operation of ancient tank furnaces to make glass and pot furnaces to blow glass builds a world around the objects. Swogger and I also co-wrote Dig Deeper: Discovering the Ancient Glass Workshop at Jalame, a 36-page comic book about the Jalame excavations which accompanies the exhibition.

The Corning Museum also built a wood-fueled furnace modeled on those constructed by Mark Taylor and David Hill (“The Glassmakers”, specialists in recreating ancient Roman glass). We filmed a series of videos showing glassblowing at the furnace and how various types of discarded debris would have been formed and discarded at the site. Public demonstrations and livestreams will continue through the summer.

The exhibition concludes with a contemplation of the role of archaeology and museum collections in the 21st century. Ghosts is a series inspired by ancient glass vessels, designed by the Palestinian artist Dima Srouji and produced by Hollow Forms in Jaba’ in the occupied West Bank. The ethereal objects comment on the dispersal of the glass heritage from the region into western collections. Finally, a list of resources highlighting community archaeology projects and responsible ways for visitors to get involved in archaeology is posted on the exhibition website and accessible via a QR code in the gallery.

Katherine A. Larson is Curator of Ancient Glass at The Corning Museum of Glass. Dig Deeper: Discovering an Ancient Glass Workshop opened May 13, 2023 and runs through January 7, 2024. Research for the exhibition was supported in part by an ASOR Study of Collections Fellowship. For more information, visit http:cmog.org/dig-deeper.

Further Reading:

Gladys Davidson Weinberg, ed. 1988. Excavations at Jalame: Site of a Glass Factory in Late Roman Palestine. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

Kathleen Warner Slane and Jodi Magness. 2005. “Jalame Restudied and Reinterpreted.” Rei Creatariae Romanae Fautorum Acta 39: 257–61.

’Abed a-Salam Sa’id, and Yael Gorin-Rosen. 2022. “Khirbat ’Asafna.” Hadashot Arkheologiyot 134 (September).

Want To Learn More?

Glass: Lapis Lazuli from the Kiln

By Andrew Shortland

Today glass is all around us. But when glass was first made in the Late Bronze Age around 1500 BCE it was very different. How was this magical “stone from the kiln” made and what did it mean to its makers? Read More

(Hi)stories Set in Plaster: Ancient Western Asian Reproductions and the Berlin State Museums

By Pınar Durgun

For 200 years plaster copies of ancient objects have been created for education, preservation, collaboration, and public access. The pandemic has given them new relevance. Read More