May 2016

Vol. 4, No. 5

“So it is Written, So it Shall be Done:” The Ten Commandments at 60

By Alex Joffe

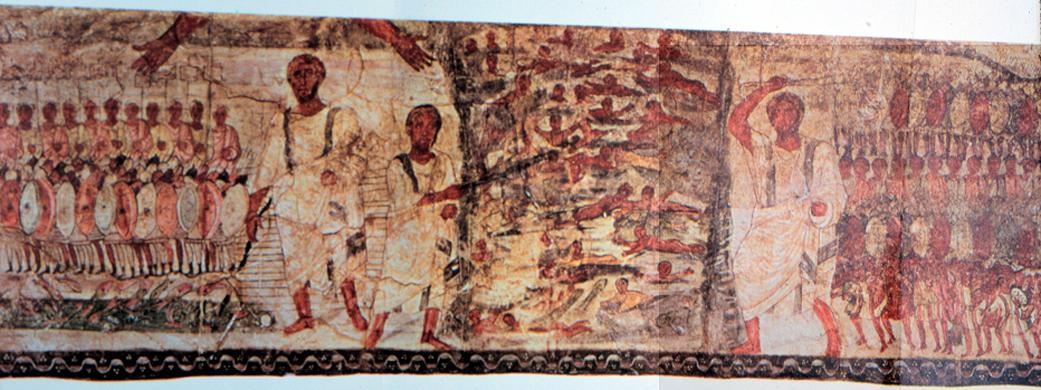

Who was Moses and what was the Exodus? The Book of Exodus contains 40 chapters but the very human desire to express these narratives in imagery has been evident for millennia. In the Dura-Europos synagogue from the 3rdcentury CE Moses appears three times across a single panel, leading the Israelites out of Egypt, across the Red Sea, and then organized into Twelve Tribes, all below the guiding hands of God.

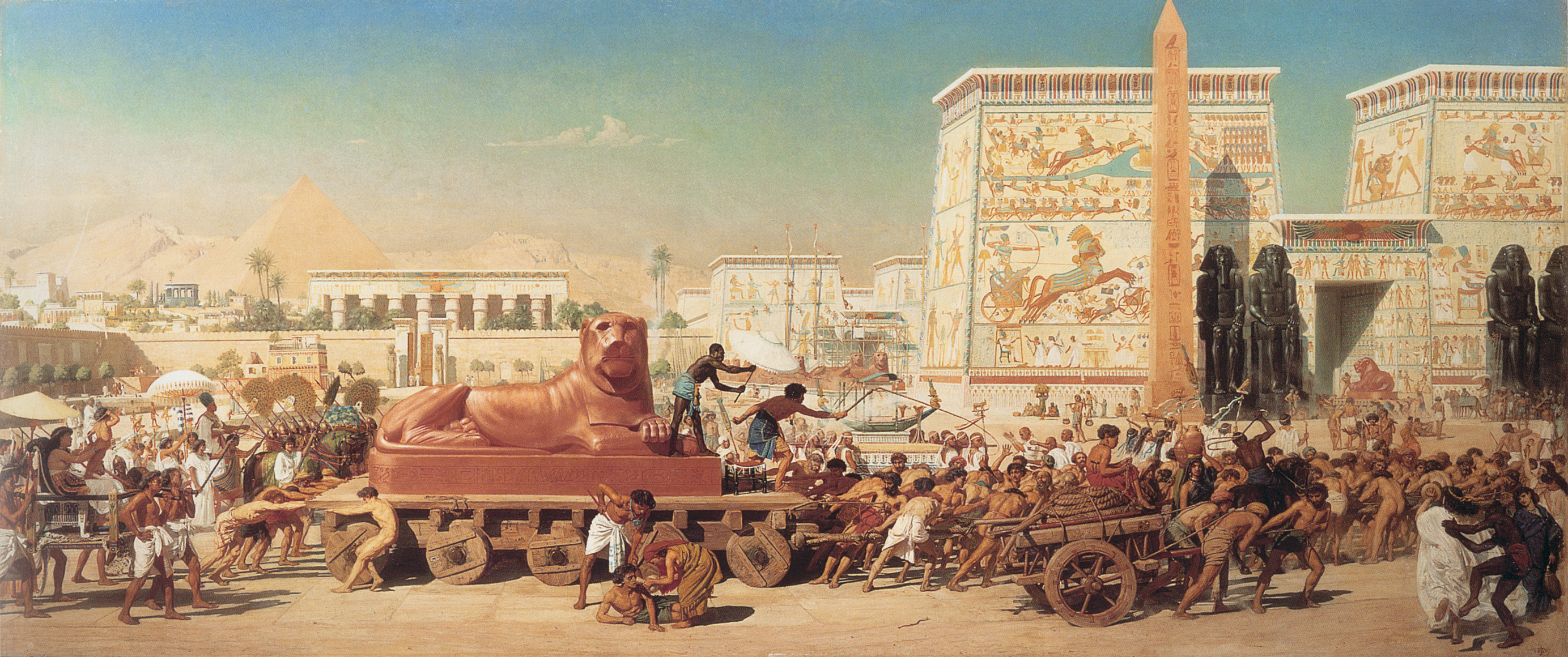

But how do we visualize these moments of liberation today? For any American over 50 there is only one answer; Charlton Heston and Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments. If 19th century Britons visualized the Exodus in terms of paintings by David Roberts or Edward Poynter, The Ten Commandments is – or perhaps was – America’s definitive visual contribution.

A massive hit when it first appeared in 1956, for decades the film was an interfaith Easter and Passover television staple, where millions crowded around black and white or primitive color TV’s to watch an epic that had been shot in the widest screen format ever invented. Now at 60, how are we to think of the film?

The Ten Commandments must first be spoken of in terms of its director, Cecil B. DeMille. Today DeMille is rarely thought of as one of America’s leading directors. But for over four decades he directed, produced and wrote a bewildering assortment of films; frothy comedies like Madam Satan, potboilers like The Cheat, historical dramas such as Cleopatra, and high dramas like The Greatest Show on Earth. Though he directed at least 80 films he is, perhaps unfairly, best known for his Biblical epics, Samson and Delilah, Sign of the Cross, King of Kings, and two versions of The Ten Commandments.

DeMille’s original 1923 version of The Ten Commandments saw the Exodus story paired against a modern tale of corruption and redemption. The story of the two McTavish brothers, one a poor carpenter, the other a rich contractor, and the construction of a church with substandard concrete, the collapse of which (spoiler alert) kills their poor grey haired mother, was heavy handed allegory and awkward storytelling. The Americanization of the Exodus story juxtaposed Biblical and “modern” values but proved popular with audiences.

When DeMille undertook to remake the film in the early 1950s his own fame was long established. Allegory was jettisoned in favor of a mostly literal retelling of the Exodus story. The newly developed VistaVision technique, which exposed a 35mm negative sideways, produced a widescreen experience in finely detailed and lush Technicolor.

American film and public tastes had changed in the three decades since DeMille’s first film and the industry’s ability to create epics – in terms of storytelling and visuals – was at its height. The top grossing films of 1956 included The Ten Commandments, Around the World in 80 Days, Giant, War and Peace, and The Searchers. One way that DeMille strove for epic dimensions was through historical accuracy, which also became a canny marketing point.

DeMille’s researcher, Henry S. Noerdlinger, consulted numerous Biblical scholars and Egyptologists, and the film’s visual details were rendered faithfully according to the scholarship of the day. Noerdlinger even produced a book, Moses and Egypt, which detailed the Biblical translations, Egyptian sources, and other materials behind the film, down to analyses of the thread counts in ancient Egyptian linen. In effect Rameses III’s Medinet Habu wall carvings come to life, with scenes of the Nile, Egyptians and their foes. But this provides an ironic sort of authenticity; an elite ancient Egyptian vision is translated into a dynamic expression where the king and his minions are the bad guys.

An epic product (a posterior numbing 3 hours and 40 minutes worth) also required an epic scale of production. The widescreen format provides a scale rarely seen today, a fitting tableau for the enormous sets and masses of extras. The location sets in Egypt were the largest ever built. One of the two water tanks built on the Paramount back lot for the Red Sea was reportedly 300 feet on each side.

The matte paintings that created background landscapes, pyramids, and mountains, were the pinnacle of the art, as were the incredibly complicated optical compositing techniques, which used up to 12 separate negatives to create the final image. These techniques create an artistic feeling that connects the film to classic paintings. But to a 21st century eye accustomed to computer animation, they feel static.

The Egyptian sets are magnificent, enormous, glossy and detailed, populated by hundreds of costumed extras. But the staging, perhaps inadvertently, goes beyond ‘authenticity’ –the lingering sense of Hollywood grandiloquence generates suspicion that the next day Gene Kelly might stage a gigantic dance scene on the same set. The score by Elmer Bernstein, soaring and heroic, also raises the film up but sets it as a mid-century production.

When the action moves to medium shots of Moses (played by Heston’s infant son Fraser) being rescued from the Nile, Israelites working in mud pits, or the alleys of Pithom, there is little sense of scale, depth, or dirt; these studio sets fall flat. Sadly, the most important divine interventions, the Burning Bush, Pillar of Fire, Moses’ staff transformed into a snake, and the fiery creation of the tablets of the law, are animated. These flaming cartoon effects are about as unpersuasive as the ‘monster from the id’ in another 1956 hit, Forbidden Planet. On this we may pine for modern special effects.

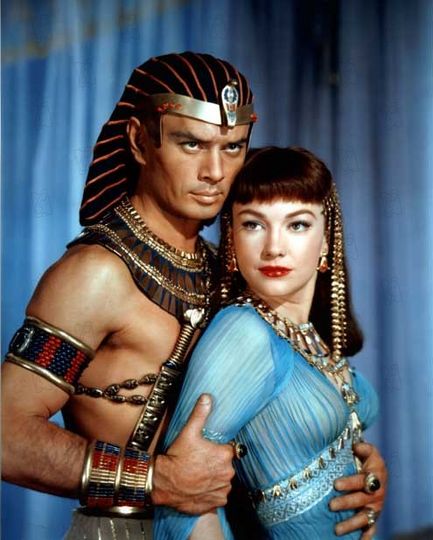

But the film’s heart is the acting, namely the scenery chewing love triangle of Heston, Yul Brynner, and Anne Baxter. Heston – chosen in part because of his resemblance to Michelangelo’s Moses – projects a stolid Upper Midwestern masculinity that is associated with few actors today. Unlike his revolutionary contemporary, Marlon Brando, Heston’s emotion and vulnerability had to be accessed through a hard shell. There is a straight line through Heston’s most famous roles, from Moses to Ben-Hur, all the way to George Taylor, marooned on a planet of damned, dirty apes. He is slow to be provoked, but then, watch out.

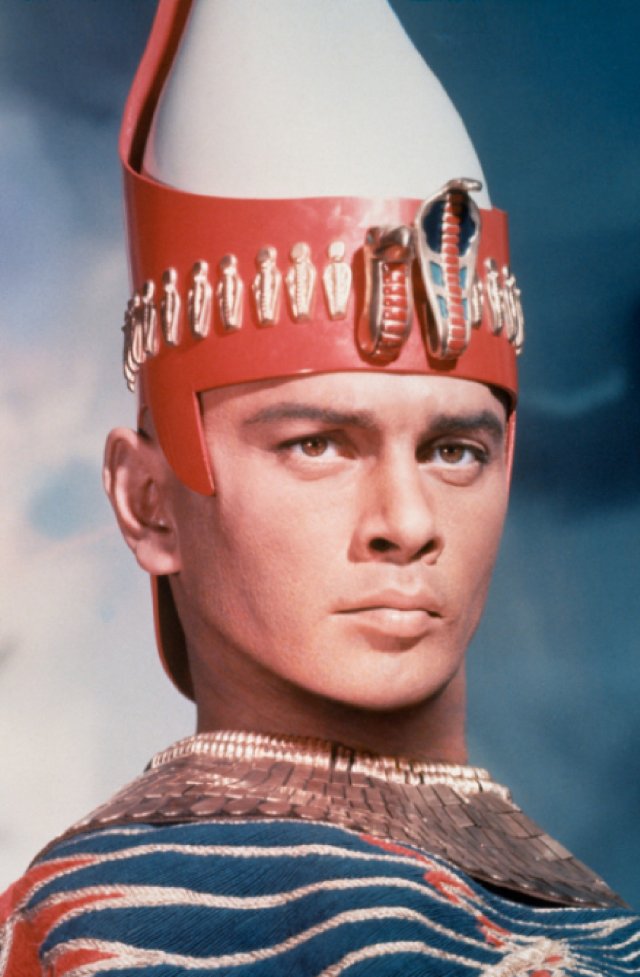

In contrast, the Siberian born Brynner exuded exoticism, befitting a role like the King Mongkut of Siam, for which he had become famous in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The King and I. His Rameses is also played within a narrow emotional range, with quiet seething and few outbursts. But Brynner’s natural authority was critical to projecting both Rameses’s imperiousness and blindness.

Finally, there is Ann Baxter, granddaughter of a Frank Lloyd Wright and a Hollywood journey woman, who plays the vampish Queen Nefretiri as a manipulative bad girl. The subplot of her short-lived romance with Moses then unhappy marriage to Rameses is entirely invented and gives the film a 1940s feeling of love triangles and femme fatales. But Baxter reliably delivers some of the film’s cheesiest (“Oh, Moses, Moses, you stubborn, splendid, adorable fool!”) and most bitter lines (“You let Moses kill my son. No god can bring him back. What have you done to Moses? How did he die? Did he cry for mercy when you tortured him? Bring me to his body! I want to see it, Rameses! I want to see it!”)

To the modern eye, or certain modern sensibilities, the primary cast is also disconcertingly “white.” To counter we might point to the brief presence of the distinguished African American actor, and professional football player, Woodrow Strode, as the Ethiopian King, and several thousand Egyptian Army personnel as, well, the Egyptian Army. Like any film, it is a product of its times.

For every exceptional actor like Cedric Hardwicke (Seti) or Nina Foch (Bithia) there are one-dimensional hacks like John Derek (Joshua) or the annoying girls who played Jethro’s daughters as giggly flibbertigibbets. Still, DeMille was both a craftsman and eminently practical; rope swinging hunks like Derek were box office draws, and veteran character actors like Edward G. Robinson, Vincent Price and John Carradine kept the non-Biblical B-story going when Heston and Brynner were off screen.

But does it still work? The real star of The Ten Commandments is God, who speaks directly to Moses and works miracles that ultimately convince Rameses to let the Israelites go. Divine intervention and national liberation is the essence of the Biblical account. What a contrast with Ridley Scott’s 2014 retelling, where Moses is a freedom fighter and God a vision on by a blow to the head of a child brought, or the 1998 animated Prince of Egypt, where Moses cries because of the plagues and with musical numbers that sound like rejects from Frozen.

In 1923 DeMille made two parallel stories to highlight the decay of modern values, but in 1956 he opted for a more subtle approach. He makes God the star, and liberation the central theme, and through clever dialogue and narration Americanizes the Exodus once again. But Cold War made the stakes far higher than even those that killed Mrs. McTavish. “Man took dominion over man – the conquered were made to serve the conqueror – the weak made to server the strong,” the narrator – DeMille himself – intones. Moses’ last words in the film, “Go – proclaim liberty throughout all the lands, unto all the inhabitants thereof” (Leviticus 25:10), also inscribed on the Liberty Bell, make the connection between ancient Israel and America clear.

Film tells us not ‘who we are’ but how we see ourselves at any given moment. Perhaps every generation gets The Ten Commandments that it wants. There are no ‘timeless’ films but DeMille’s The Ten Commandments comes closer than many, because of its subject matter, epic scale, and outsized social impact. Whether its messages of human liberty and the enduring relationship of God and the Israelites still resonate, in America or elsewhere, is another question.

Alex Joffe is the editor of The Ancient Near East Today.

~~~

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this blog or found by following any link on this blog. ASOR will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information. ASOR will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. The opinions expressed by Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of ASOR or any employee thereof.